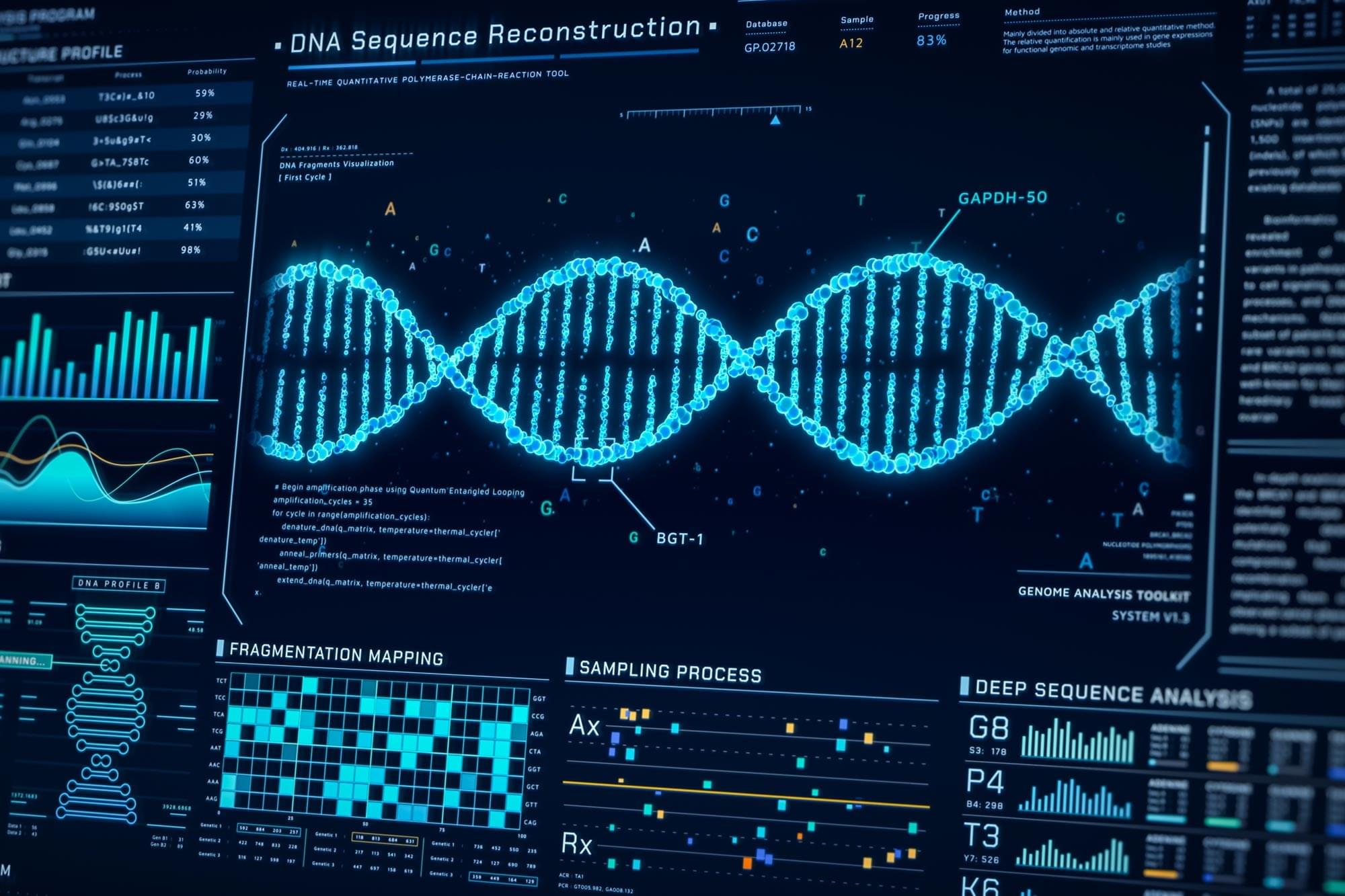

When disease begins forming inside the human body, something subtle happens long before symptoms appear. Individual molecules such as DNA, RNA, peptides, or proteins begin shifting in quantity or shape. Detecting these tiny molecular changes early could dramatically change how cancer, infections, and other conditions are diagnosed.

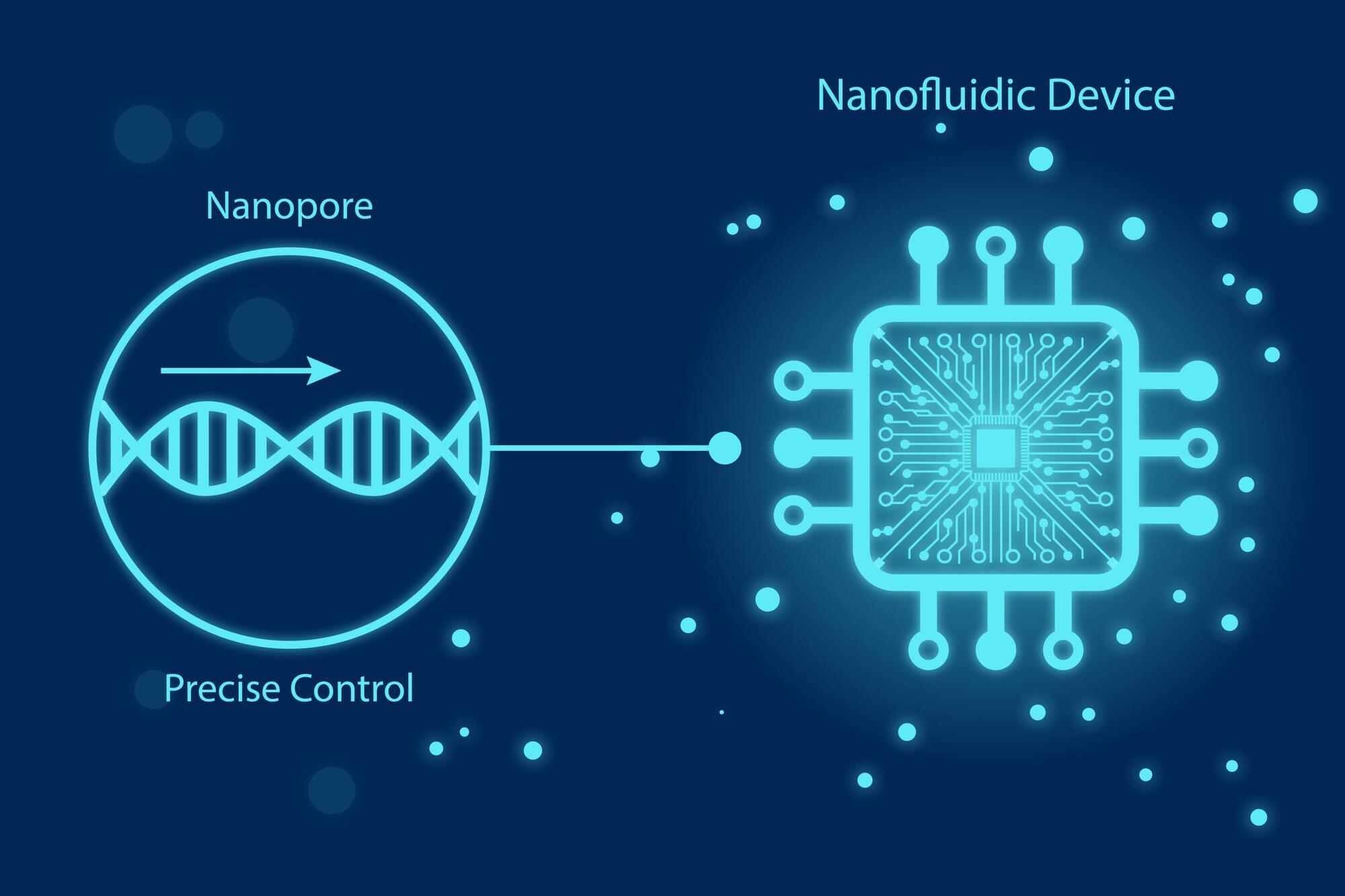

For years, scientists have dreamed of reading these changes one molecule at a time. Nanopores, nanometer-sized holes that detect single molecules by sensing changes in electric current, have brought that dream closer to reality, but nanopore sensing has hit several scientific walls.

Molecules rush through too fast to analyze. Signals drown in electrical noise. Proteins stick to pore surfaces and single pores simply cannot provide the scale required for real-world clinical use. So what would it take to make nanopore sensing fast, precise, and robust enough for society?