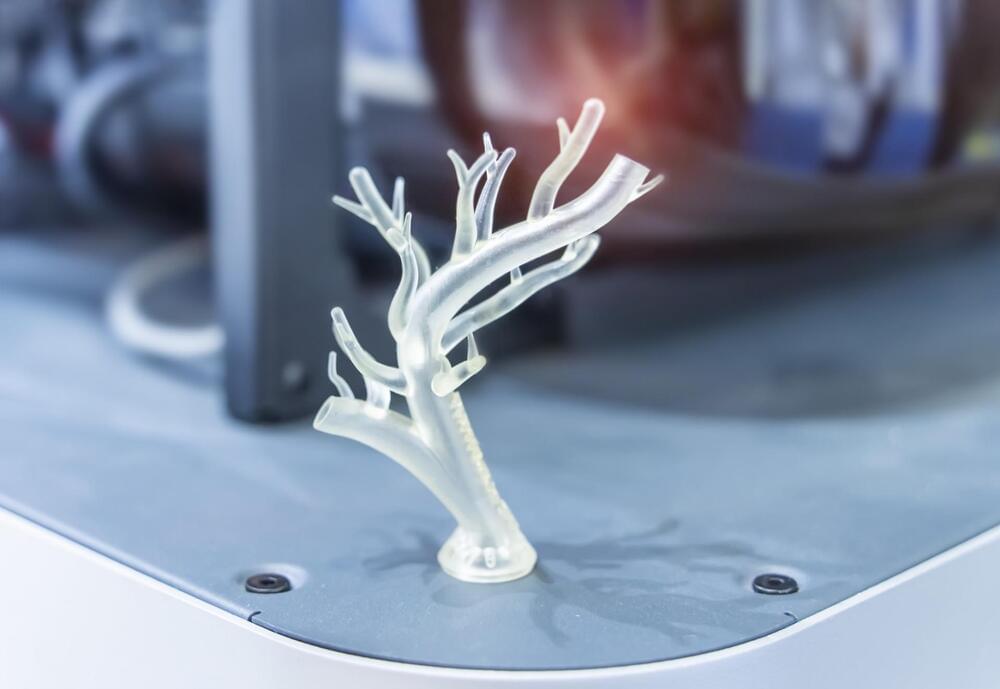

Scientists can now 3D print more-realistic prosthetic eyes in a fraction of the time and effort required by traditional approaches.

Imagine being able to build an entire dialysis machine using nothing more than a 3D printer.

This could not only reduce costs and eliminate manufacturing waste, but since this machine could be produced outside a factory, people with limited resources or those who live in remote areas may be able to access this medical device more easily.

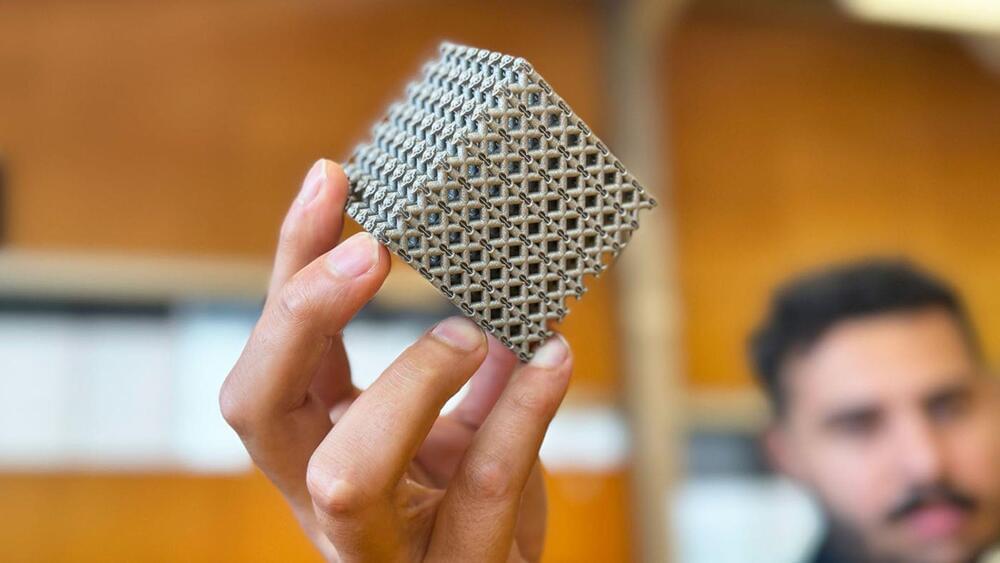

While multiple hurdles must be overcome to develop electronic devices that are entirely 3D printed, a team at MIT has taken an important step in this direction by demonstrating fully 3D-printed, three-dimensional solenoids.

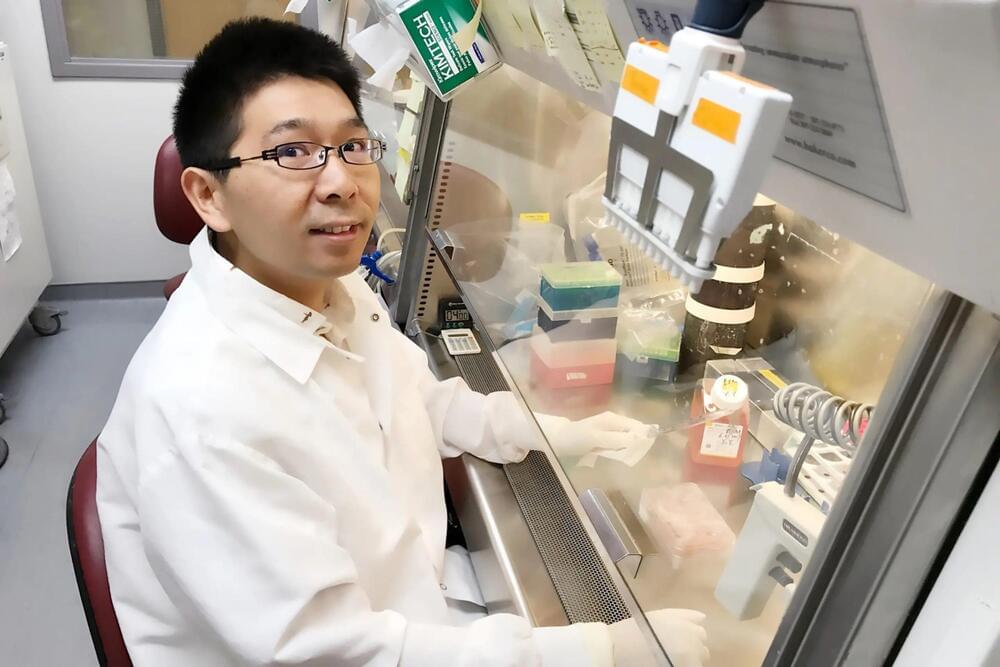

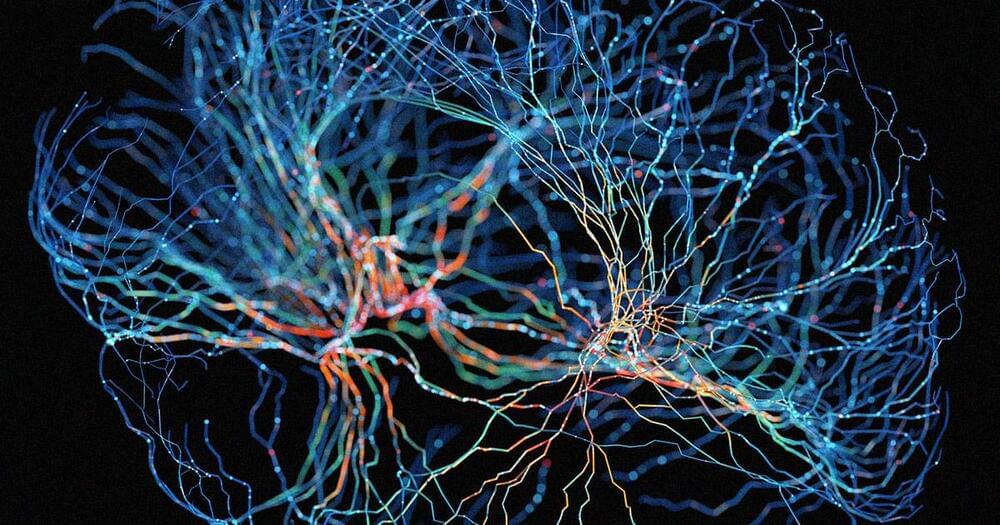

Researchers from the University of Wisconsin-Madison (UW-Madison) have developed a novel approach for 3D printing functional human brain tissue.

The 3D printing process can create active neural networks in and between tissues that grow in a matter of weeks.

The researchers believe that their 3D bioprinted brain tissue provides an effective tool for modeling brain network activity under physiological and pathological conditions, and can also serve as a platform for drug testing.

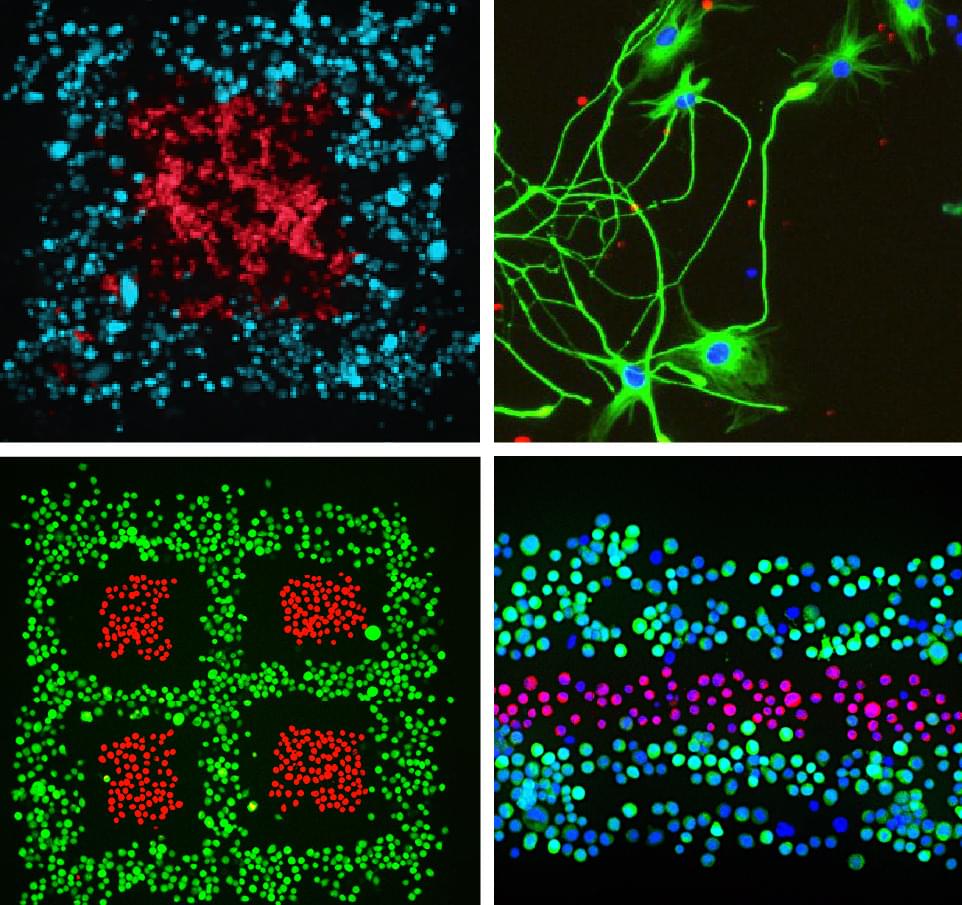

Scientists from medical tech company Fluicell have partnered with clinical R&D firm Cellectricon and the Swedish Karolinska Institutet university to 3D bioprint neural cells into complex patterns.

Using the microfluidic printheads featured on Fluicell’s Biopixlar platform, the researchers were able to accurately arrange rat brain cells within 3D structures, without damaging their viability. The resulting cerebral tissues could be used to model the progress of neurological diseases, or to test the efficacy of related drugs.

“We’ve been using Biopixlar to develop protocols for the printing of different neuronal cells types, and we are very pleased with its performance,” said Mattias Karlsson, CEO of Cellectricon. “This exciting technology has the potential to open completely new avenues for in-vitro modeling of a wide range of central and PNS-related diseases.”

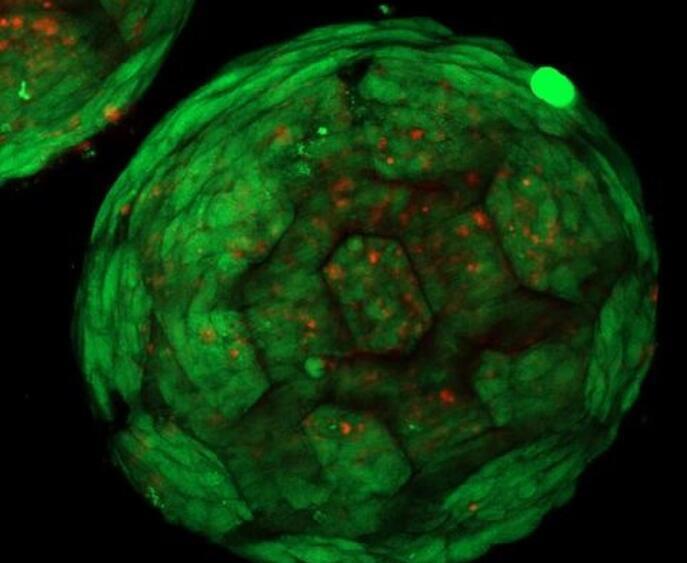

A new laser-based approach has been introduced to produce artificial cartilage using 3D printing technology.

In this approach, researchers from TU Wien printed living cells within tiny football-like spheroids.

The team hopes this technique could be used to cultivate lab-grown tissue capable of replacing damaged cartilage in humans. It is a strong connective tissue found in various parts of the body that protects our joints and bones.

In the United States, the shortage of available organs for transplantation remains a critical issue, with over 100,000 individuals currently on the waiting list. The demand for organs, including hearts, kidneys, and livers, significantly outweighs the available supply, leading to prolonged waiting times and often, devastating consequences.

It is estimated that approximately 6,000 Americans lose their lives while waiting for a suitable donor organ every year.

Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University have developed a novel tissue engineering technique that aims to potentially bridge the gap between organ demand and availability, offering a beacon of hope.

The world’s tallest 3D-printed tower, set to be built in the Swiss Alps along the Julier mountain pass, started fabrication at ETH in Zurich this month.

Tor Alva, also known as the “White Tower,” is a pioneering innovation in the 3D printing industry illustrating a 30-meter tall building in Mulegns, Switzerland.

The White Tower project was led by Benjamin Dillenburger and launched in collaboration with Fundaziun Origen.

A team of scientists at the University of Wisconsin-Madison claim to have 3D-printed functional human brain tissue for the first time.

They hope their research could open the doors for the development of treatments for existing neurological disorders, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease.

As detailed in a new paper published in the journal Cell Stem Cell, the team flipped the usual method of 3D-printing on its side, fabricating horizontal layers of brain cells encased in soft “bio-ink” gel.

Kickstarter has been the graveyard for several high-profile 3D printers. The crowdfunding platform has also introduced numerous subpar 3D printers, alongside some truly outstanding ones. It was on Kickstarter that Formlabs soared to remarkable heights. The platform also brought us the 3D printing pen. There was a period when a new 3D printing project on Kickstarter emerged every week, but both Kickstarter and additive manufacturing (AM) have become considerably less bustling recently. In 2014, things were simpler, as there were far fewer 3D printers available. Now, with the advent of Bambu Labs and sophisticated open-source 3D printers like Prusas, making a significant impact has become much more challenging. NAW 3D is currently attempting to enter the market with a pellet 3D printer on Kickstarter.

The N300 Pellet 3D Printer

NAW3D’s N300 Desktop Pellet 3D Printer boasts an automatic pellet feeding system, with a 100g capacity consumables box and a 2000cm³ material storage space for continuous printing. Additionally, all axes are equipped with linear guides. What’s more, each stage of the printer incorporates double guides. The printer’s nozzles are capable of reaching temperatures up to 300°C. The print head is designed to deposit substantial amounts of material, with printing tracks ranging from 0.2 to 2mm. This capability suggests that the printer can handle both fine details and rapid, large-scale printing tasks.