For decades, scientists have been trying to develop therapeutics for people living with Alzheimer’s disease, a progressive neurodegenerative disease that is characterized by cognitive decline. Given the global rise in cases, the stakes are high. A study published in The Lancet Public Health reports that the number of adults living with dementia worldwide is expected to nearly triple, to 153 million in 2050. Alzheimer’s disease is a dominant form of dementia, representing 60 to 70 percent of cases.

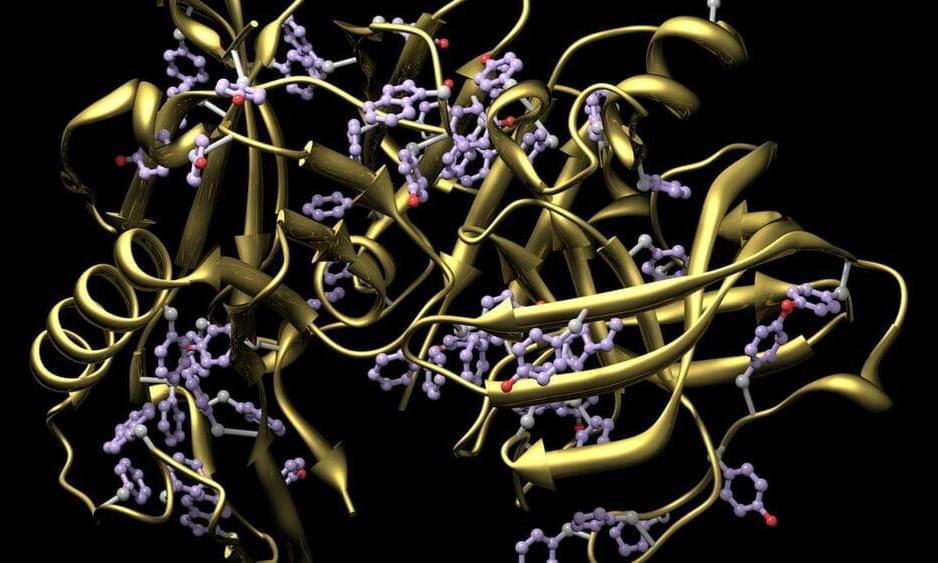

Recent approvals by the Food and Drug Administration have focused on medications that shrink the sticky brain deposits of a protein called amyloid beta. The errant growth of this protein is responsible for triggering an increase in tangled threads of another protein called tau and the development of Alzheimer’s disease — at least according to the dominant amyloid cascade hypothesis, which was first proposed in 1991.

Over the past few years, however, data and drugs associated with the hypothesis have been mired in various controversies relating to data integrity, regulatory approval, and drug safety. Nevertheless, the hypothesis still dominates research and drug development. According to Science, in fiscal year 2021 to 2022, the National Institutes of Health spent some $1.6 billion on projects that mention amyloids, about 50 percent of the agency’s overall Alzheimer’s funding. And a close look at the data for recently approved drugs suggests the hypothesis is not wrong, so much as incomplete.