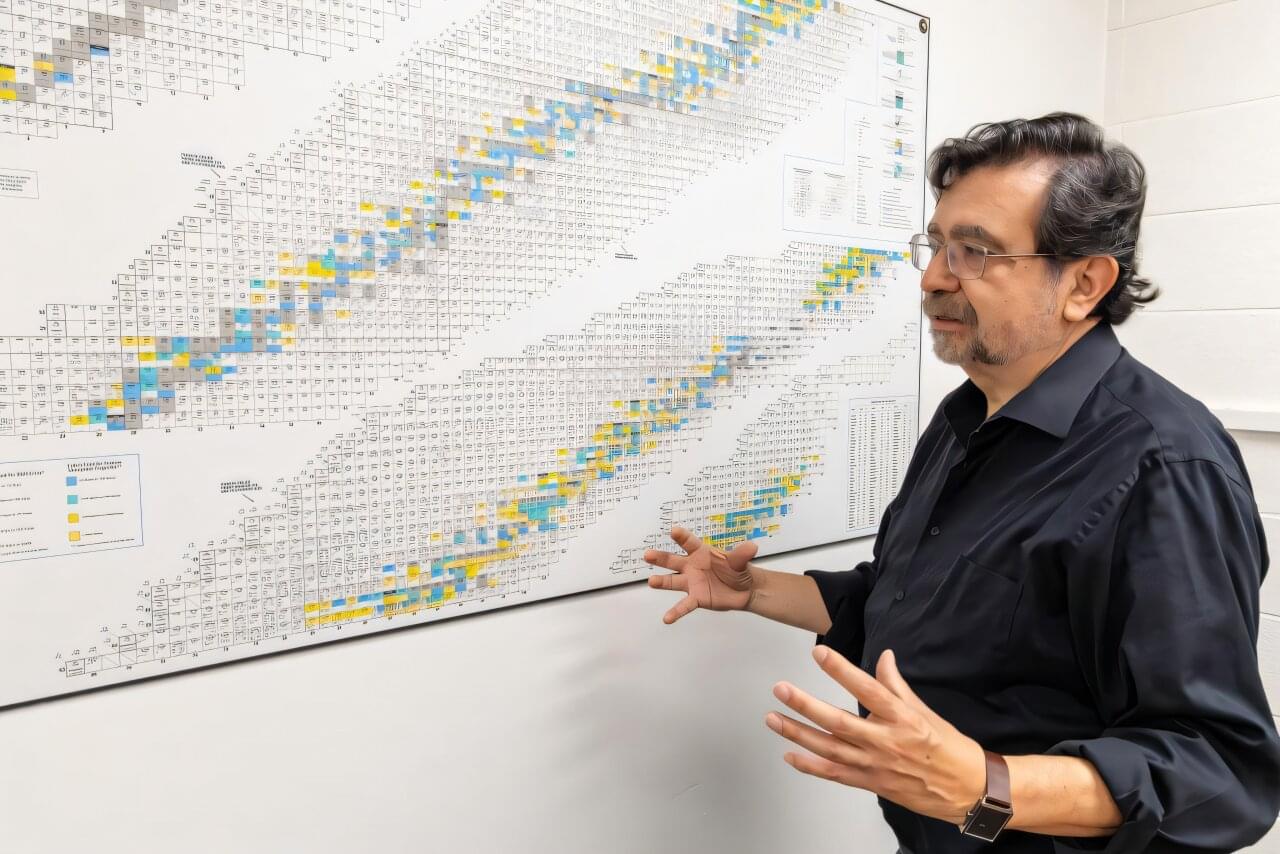

That the universe is expanding has been known for almost a hundred years now, but how fast? The exact rate of that expansion remains hotly debated, even challenging the standard model of cosmology. A research team at the Technical University of Munich (TUM), the Ludwig Maximilians University (LMU) and the Max Planck Institutes, MPA and MPE, has now imaged and modeled an exceptionally rare supernova that could provide a new, independent way to measure how fast the universe is expanding. The studies are published on the arXiv preprint server.

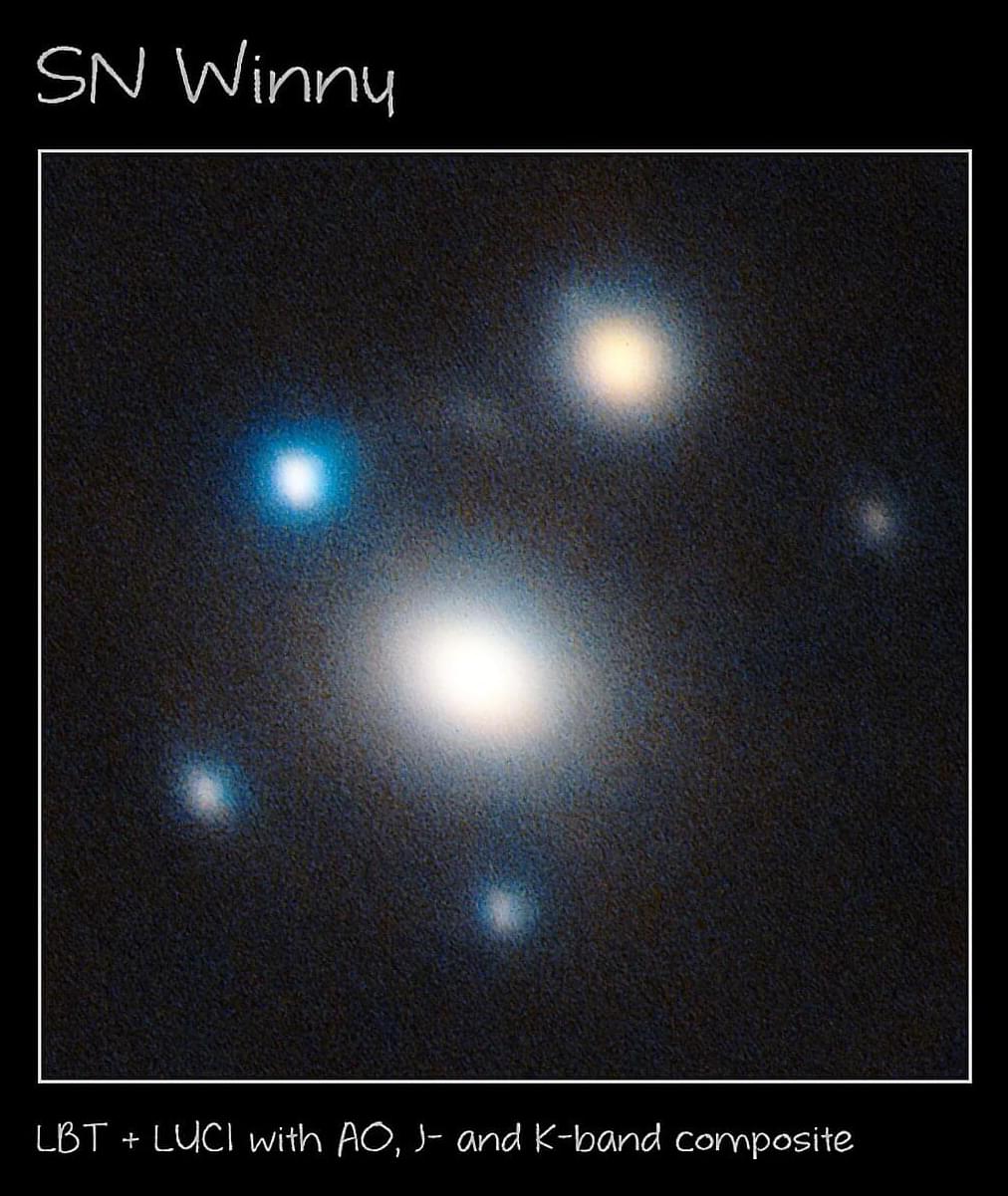

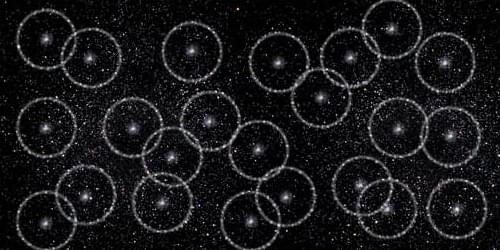

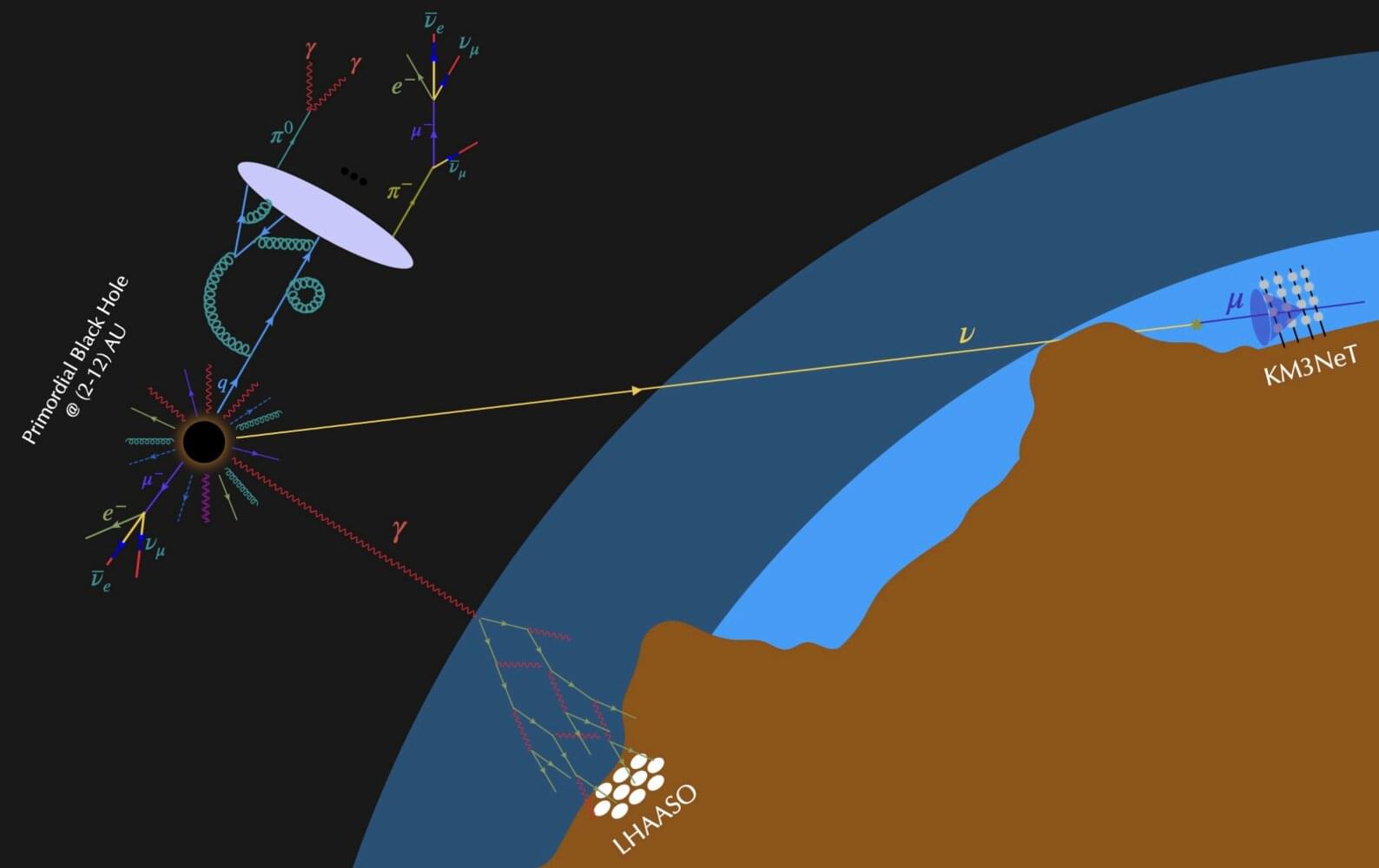

The supernova is a rare superluminous stellar explosion, 10 billion light-years away, and far brighter than typical supernovae. It is also special in another way: the single supernova appears five times in the night sky, like cosmic fireworks, due to a phenomenon known as gravitational lensing.

Two foreground galaxies bend the supernova’s light as it travels toward Earth, forcing it to take different paths. Because these paths have slightly different lengths, the light arrives at different times. By measuring the time delays between the multiple copies of the supernova, researchers can determine the universe’s present-day expansion rate, known as the Hubble constant.