Phthalates (PAEs) and bisphenol A (BPA) are significant components in plastic and its derivative industries. They are omnipresent in water sources owing to intensive industrialization and rapid urbanization, hence posing adverse effects on humans and significant environmental issues. Researchers have developed a new magnetic material, called magnetic covalent organic frameworks (MCOFs), that can effectively remove harmful chemicals like PAEs and BPA from water. Made using a special method that prevents clumping, these materials are highly porous, magnetic and reusable up to 15 times. They showed excellent removal efficiency, even at very low pollutant levels found in real river water. The study also revealed that the removal process involves strong chemical bonding. This breakthrough offers a promising, eco-friendly solution for cleaning water contaminated by plastics and industrial waste.

Read the article in Royal Society Open Science.

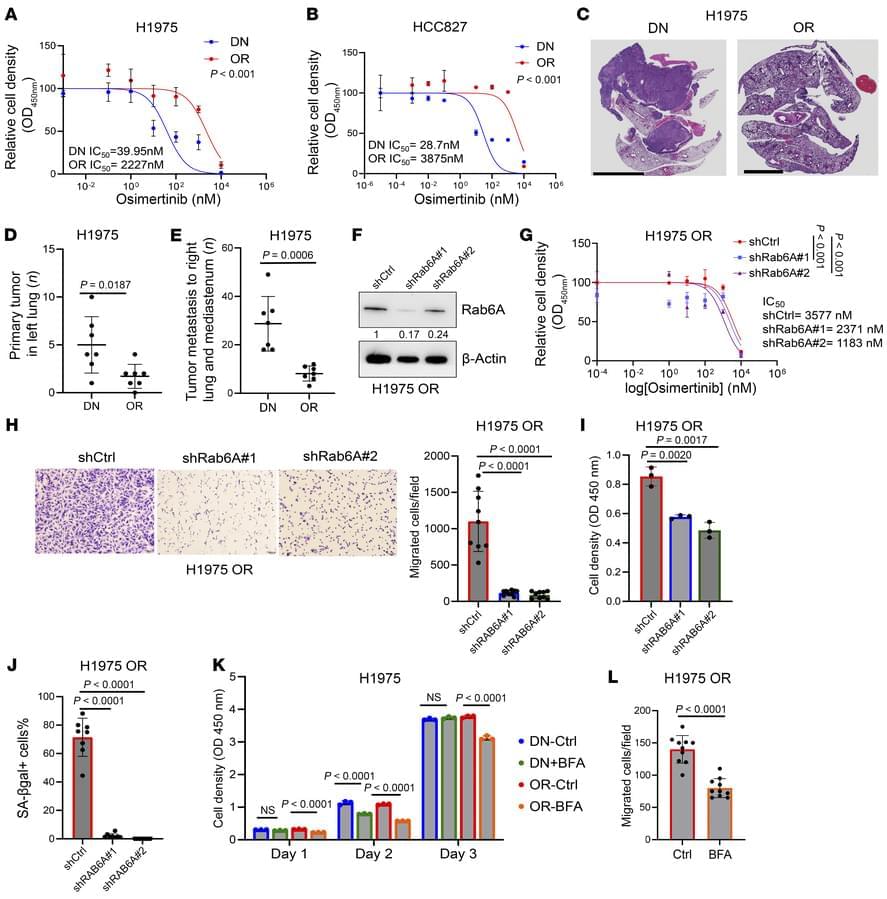

Abstract. The synthesis and characterization of effective magnetic covalent organic frameworks (MCOFs) are presented for the highly efficient adsorption of dimethyl phthalate (DMP), dibutyl phthalate (DBP) and bisphenol A (BPA) from the aqueous environment. The novelty of this research lies in the development of MCOFs through a coprecipitation method that incorporates an innovative silica inner shell. This crucial feature not only prevents aggregation of the magnetic core, which is a significant limitation of conventional adsorbents, but also enables robust interactions between the core and the outer covalent organic framework (COF). The synthesized MCOFs were comprehensively characterised using a variety of techniques. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and vibrating sample magnetometry (VSM) analyses confirmed successful synthesis and strong magnetic properties, while field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) revealed the presence of spherical, porous structures with small granules. Energy-dispursive X-ray (EDX) spectrometry analysis further confirmed the successful synthesis, showing a material composition of 58.2% Fe, 33.4% O, 4.8% C, and 3.2% Si. Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) analysis showed the MCOFs possess a high surface area of 128.1 m2 g–1 and a pore diameter of 16.8 nm, indicating abundant active sites for adsorption. Under optimal conditions (pH 7,100 mg adsorbent dosage, and 25-minute contact time) the MCOFs exhibited exceptional adsorption performance, with removal efficiencies of 90.0% for DMP, 86.0% for DBP, and 92.0% for BPA. The kinetic study revealed that the adsorption mechanism follows the pseudo-second-order model, suggesting a significant chemisorption process. Crucially, in situ FTIR analysis provided spectroscopic validation that hydrogen bonding and π–π stacking are the predominant interactions between the MCOFs and the organic contaminants. The developed analytical method achieved low detection limits of 0.0058 mg l−1 for DMP, 0.0079 mg l−1 for DBP and 0.0063 mg l−1 for BPA, indicating high sensitivity for trace-level contaminant detection in real water samples. Furthermore, the adsorbent demonstrated exceptional reusability, maintaining high performance after 15 adsorption–desorption cycles, which is a significant improvement over conventional adsorbents. This study demonstrates that MCOFs with a silica inner shell are a highly promising, stable and sustainable solution for the removal of emerging organic contaminants (EOCs).