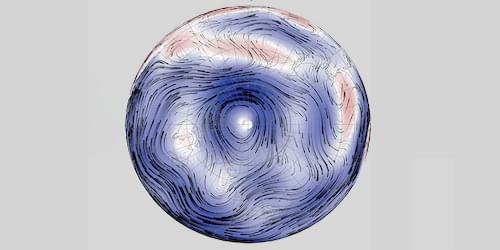

A “Little Earth Experiment” inside a giant magnet sheds light on so-far-unexplained flow patterns in Earth’s interior.

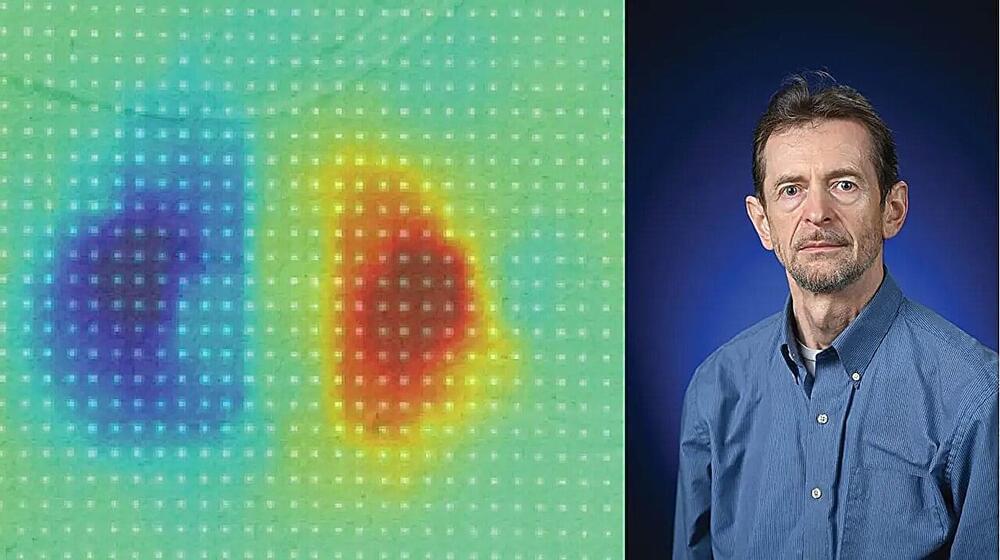

Earth’s inner core is a hot, solid ball—about 20% of Earth’s radius—made of an iron alloy. The planet’s outer core, beneath the rocky mantle, is a colder, liquid metal. Geophysics models explain that, since the movement of a liquid metal induces electrical currents, and currents induce a magnetic field, convection and rotation produce our planet’s magnetic fields. But these models typically neglect an important contribution: how Earth’s magnetic field influences the very flows that generate it. Alban Pothérat of Coventry University, UK, and collaborators have now developed a theory that accounts for such feedback and vetted it using a lab-based “Little Earth Experiment” [1]. Their results inform a model pinpointing processes that might explain the discrepancies between theoretical predictions and satellite observations of Earth, opening new perspectives on the study of geophysical flows.

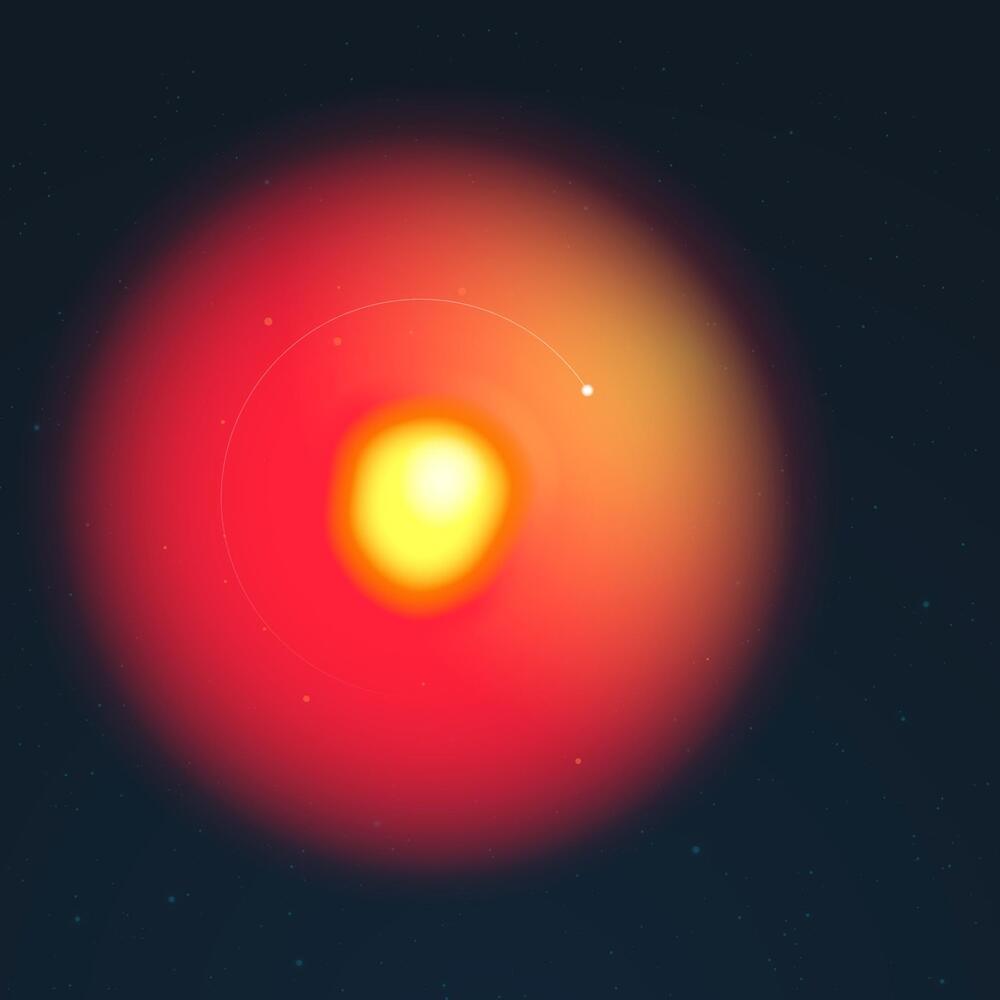

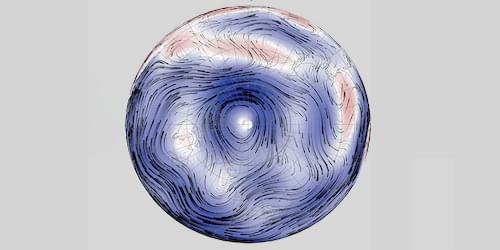

Understanding flows in planetary interiors is a long-standing challenge. “If you don’t account for the fact that the magnetic field itself changes the flow, then you won’t get the right flow,” says Pothérat. Indeed, both satellite data from the European Space Agency’s Swarm mission and state-of-the-art numerical simulations indicate certain circulating core flows where liquid produced at the boundary of the inner core is fed into the outer core, moves upward toward the poles, and from there finally flows back inward (Fig. 1).