A collaborative team of four professors and several graduate students from the Departments of Chemistry and Biochemical Science and Technology at National Taiwan University, together with the Department of Applied Chemistry at National Chi Nan University, has achieved a long-sought breakthrough.

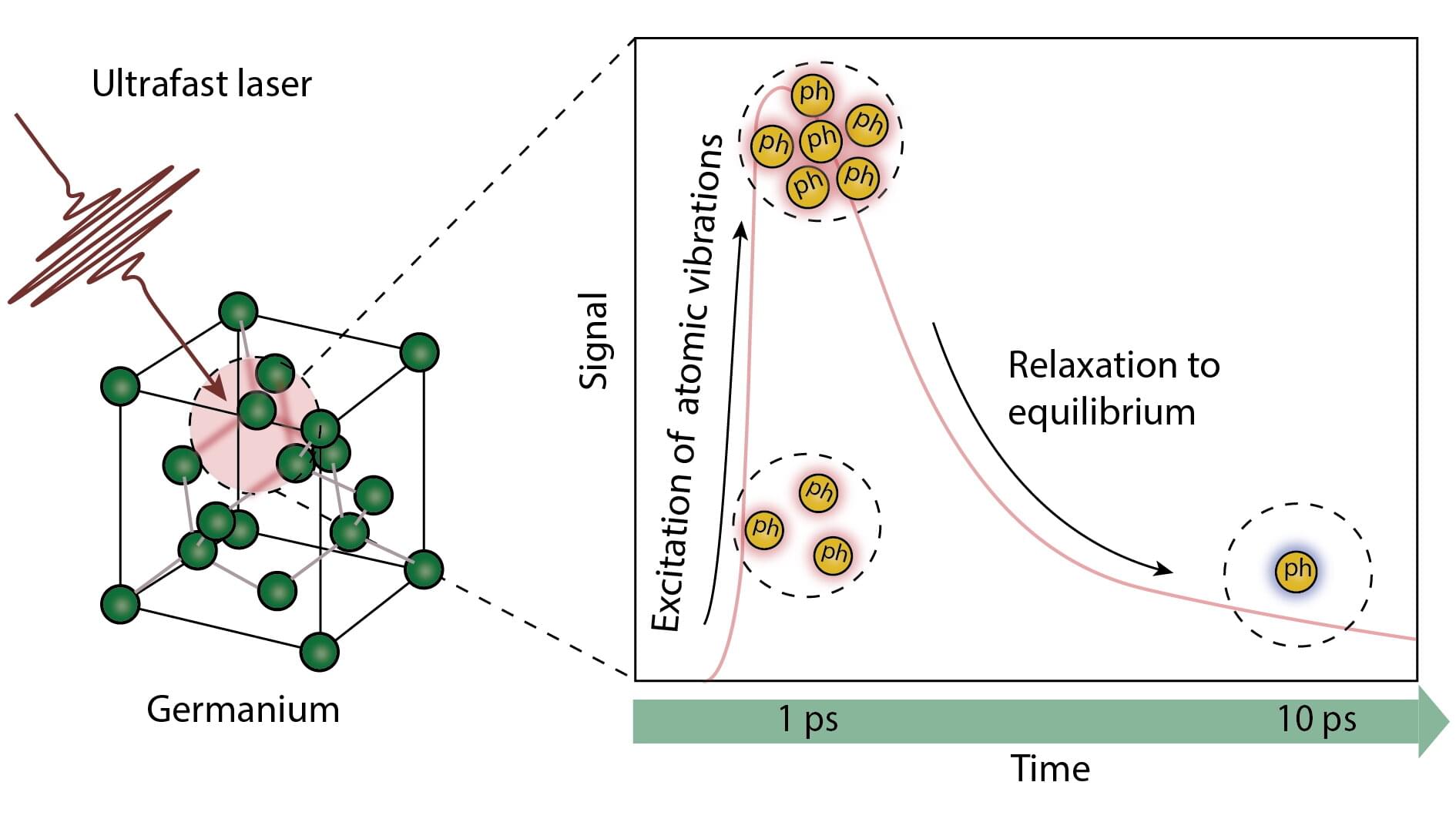

By combining atomic force microscopy (AFM) with a Hadamard product–based image reconstruction algorithm, the researchers successfully visualized, for the first time, the nanoscopic dynamics of membrane rafts in live cells—making visible what had long remained invisible on the cell membrane.

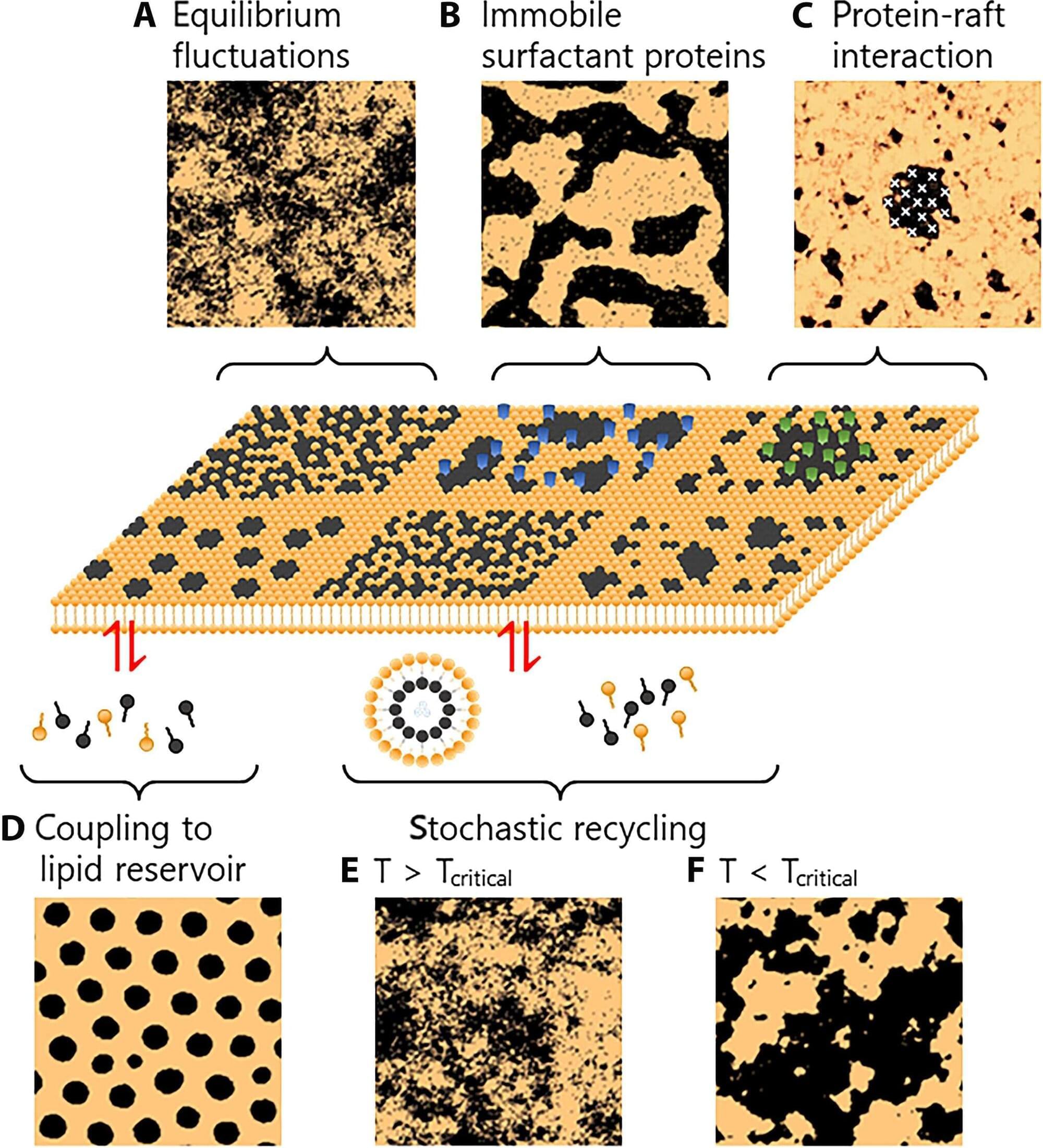

Membrane rafts are nanometer-scale structures rich in cholesterol and sphingolipids, believed to serve as vital platforms for cell signaling, viral entry, and cancer metastasis. Since the concept emerged in the 1990s, the existence and behavior of these lipid domains have been intensely debated.