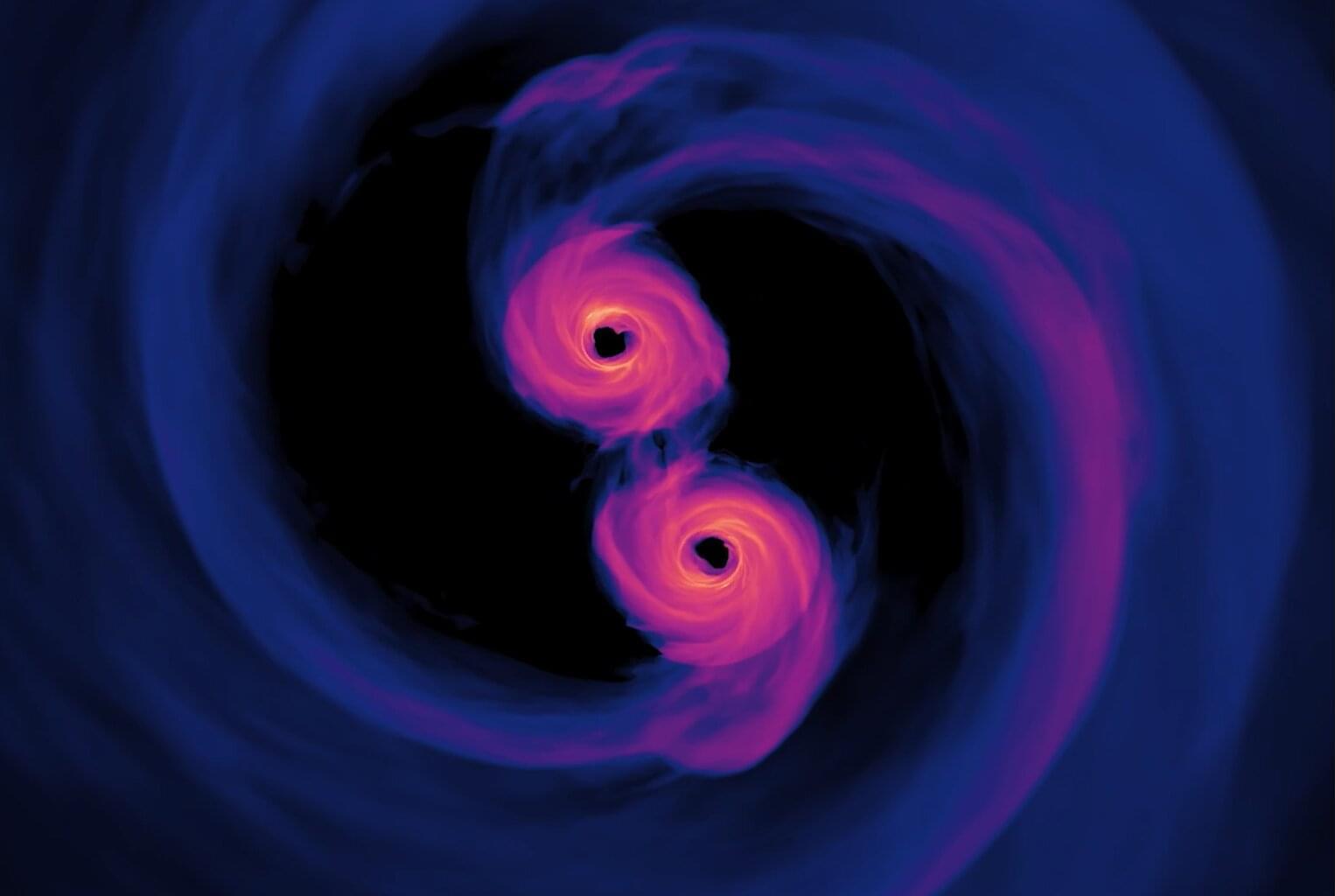

Our Milky Way galaxy may not have a supermassive black hole at its center but rather an enormous clump of mysterious dark matter exerting the same gravitational influence, astronomers say. They believe this invisible substance—which makes up most of the universe’s mass—can explain both the violent dance of stars just light-hours (often used to measure distances within our own solar system) away from the galactic center and the gentle, large-scale rotation of the entire matter in the outskirts of the Milky Way.

The new study has been published today in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.