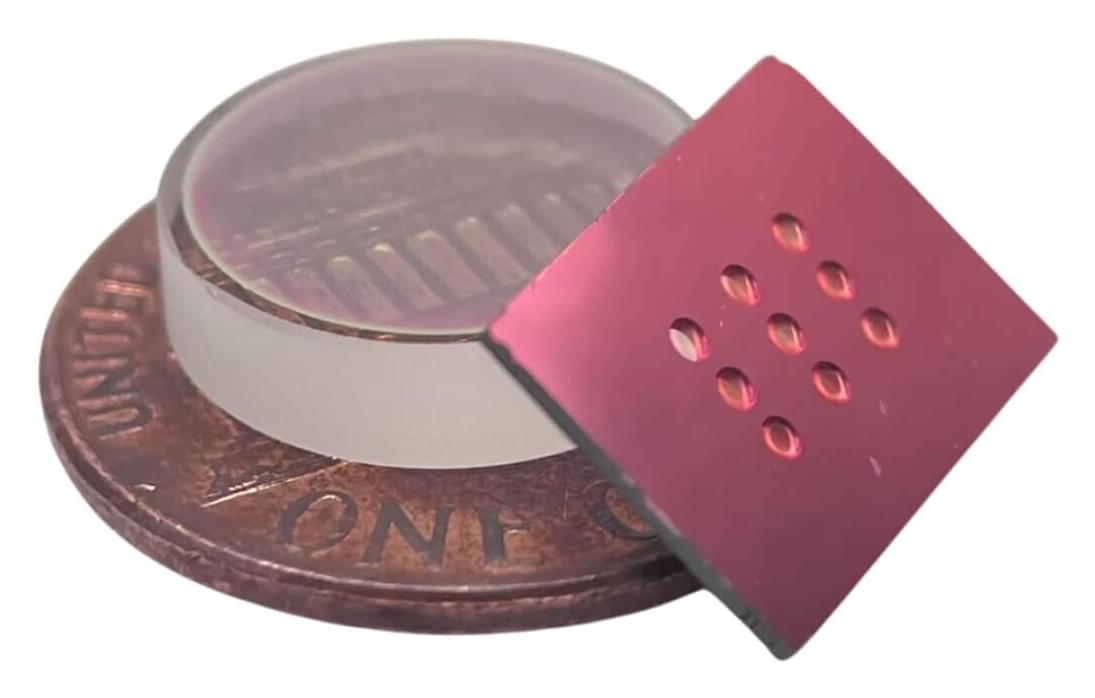

Researchers have developed a unified theory of microcavity OLEDs, guiding the design of more efficient and sustainable devices. The work reveals a surprising trade-off: squeezing light too tightly inside OLEDs can actually reduce performance, and maximum efficiency is achieved through a delicate balance of material and cavity parameters. The findings are published in the journal Materials Horizons.

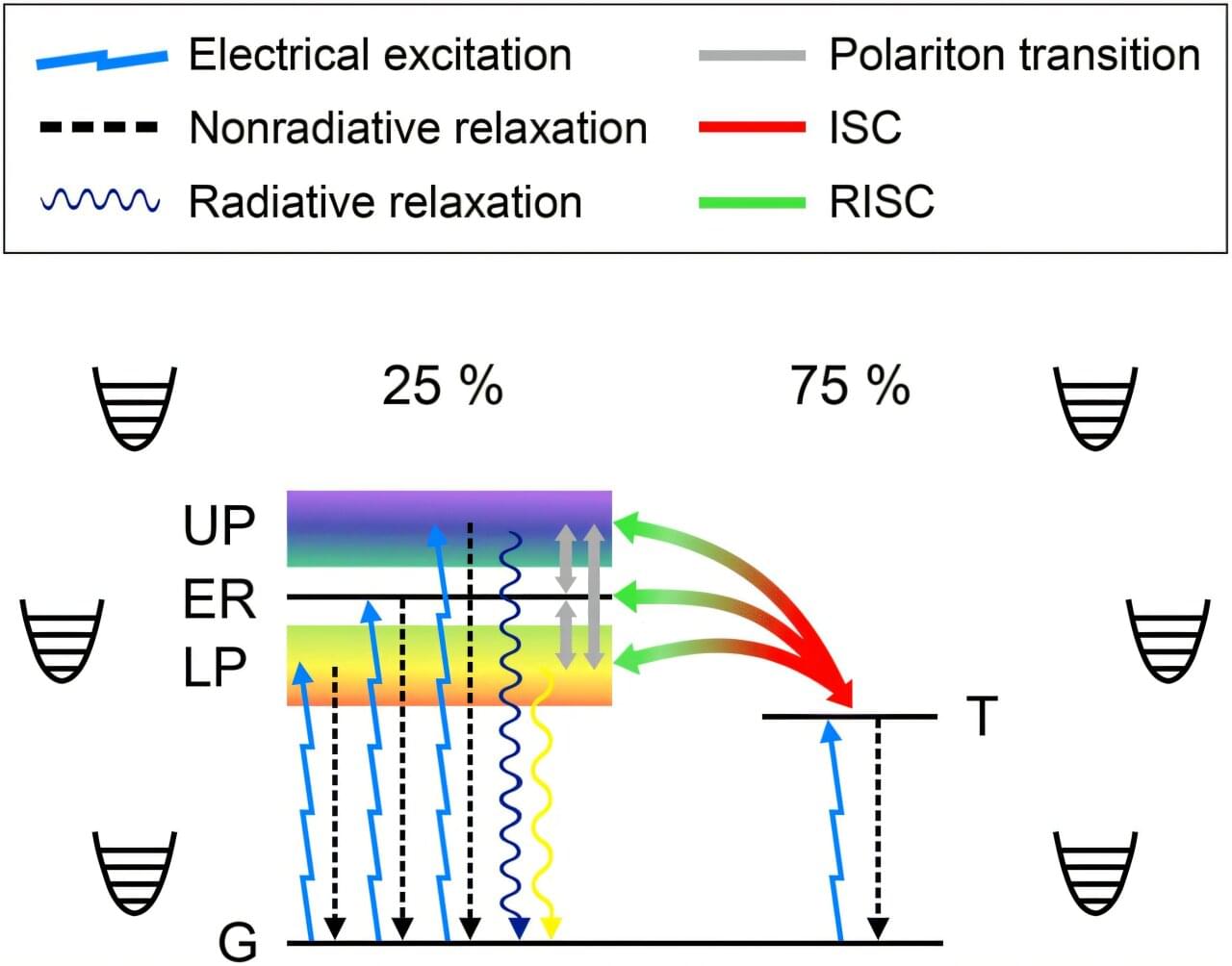

Organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) offer several attractive advantages over traditional LED technology: they are lightweight, flexible, and more environmentally friendly to manufacture and recycle. However, heavy-metal-free OLEDs can be rather inefficient, with up to 75% of the injected electrical current converting into heat.

OLED efficiency can be enhanced by placing the device inside an optical microcavity. Squeezing the electromagnetic field forces light to escape more rapidly instead of wasting energy as heat. “It is basically like squeezing toothpaste out of a tube,” explains Associate Professor Konstantinos Daskalakis from the University of Turku in Finland.