Can sleep improve language learning? New neuroscience explains how sleep strengthens vocabulary, pronunciation, and memory.

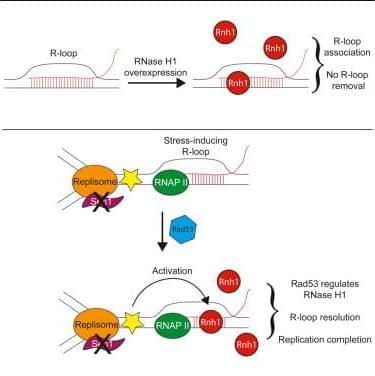

Wagner et al. demonstrate that RNase H1 only removes a subset of R-loops in vivo. In yeast, overexpressed RNH1 acts more frequently at dysregulated R-loops and infrequently, if at all, at other RNA-DNA hybrids. Endogenous Rnh1 is induced in a Rad53-dependent manner at transcription-replication conflicts to promote replication completion.

Quantum information theory is a field of study that examines how quantum technologies store and process information. Over the past decades, researchers have introduced several new quantum information frameworks and theories that are informing the development of quantum computers and other devices that operate leveraging quantum mechanical effects.

These include so-called resource theories, which outline the transformations that can take place in quantum systems when only a limited number of operations are allowed.

In 2008, two scientists at Imperial College London introduced what they termed the generalized quantum Stein’s lemma, a mathematical theorem that describes how well quantum states can be distinguished from one another. In this generalized setting, one typically considers multiple identical copies of a specific state (the null hypothesis) and tests them against a composite alternative hypothesis, i.e., a set of states (e.g., resource-free states).

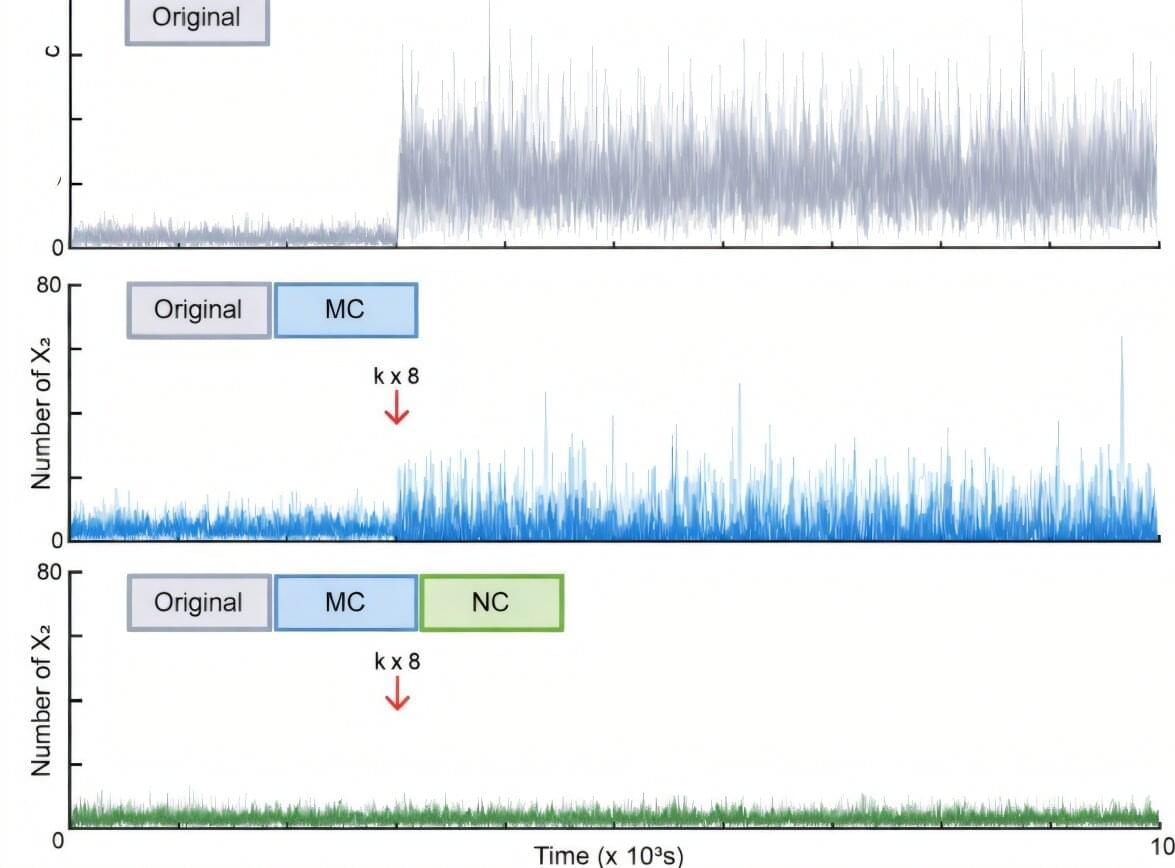

Why does cancer sometimes recur even after successful treatment, or why do some bacteria survive despite the use of powerful antibiotics? One of the key culprits identified is “biological noise”—random fluctuations occurring inside cells.

Even when cells share the same genes, the amount of protein varies in each, creating “outliers” that evade drug treatments and survive. Until now, scientists could only control the average values of cell populations; controlling the irregular variability of individual cells remained a long-standing challenge.

A joint research team—led by Professor Jae Kyoung Kim (Department of Mathematical Sciences, KAIST), Professor Jinsu Kim (Department of Mathematics, POSTECH), and Professor Byung-Kwan Cho (Graduate School of Engineering Biology, KAIST)—has theoretically established a “noise control principle.” Through mathematical modeling, they have found a way to eliminate biological noise and precisely govern cellular destiny.

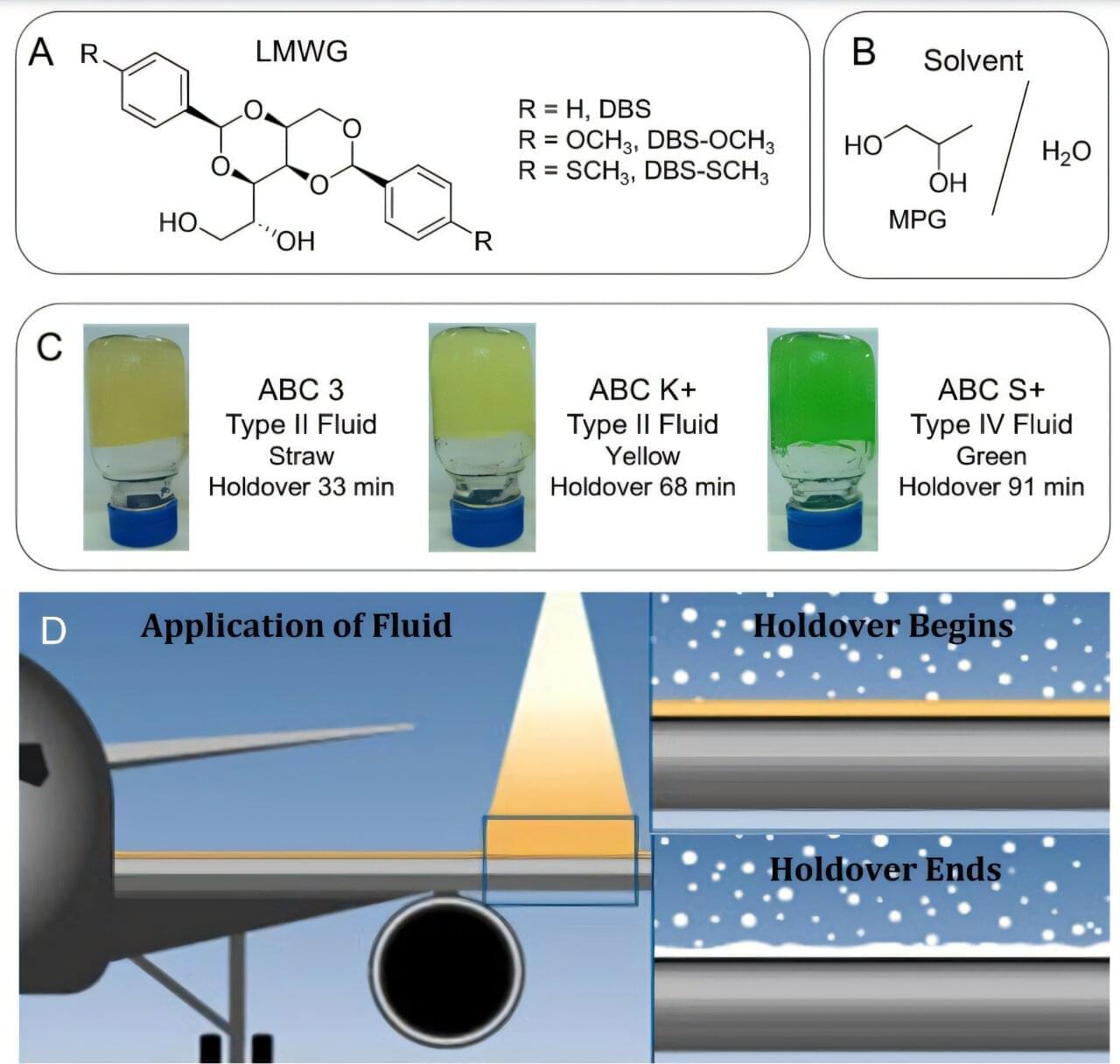

Tiny molecules already used to thicken everyday products like lotions and adhesives may soon help keep aircraft safe in icy conditions. These molecules, known as low-molecular-weight gelators (LMWGs), can self-assemble into soft, gel-like structures and have long been used in industrial formulations.

In a study published in Langmuir, researchers report that adding just small amounts of these molecules can significantly improve the performance of aircraft anti-icing fluids.

The team modified commercial deicing and anti-icing fluids—which already contain polymers for protective coating—by incorporating LMWG molecules to produce a hybrid gel formulation. They tested three variants of a gelator, known as DBS (1,3:2,4-dibenzylidenesorbitol), at varying levels of aviation-grade agents used to remove existing ice and prevent new ice formation on aircraft surfaces during ground operations.

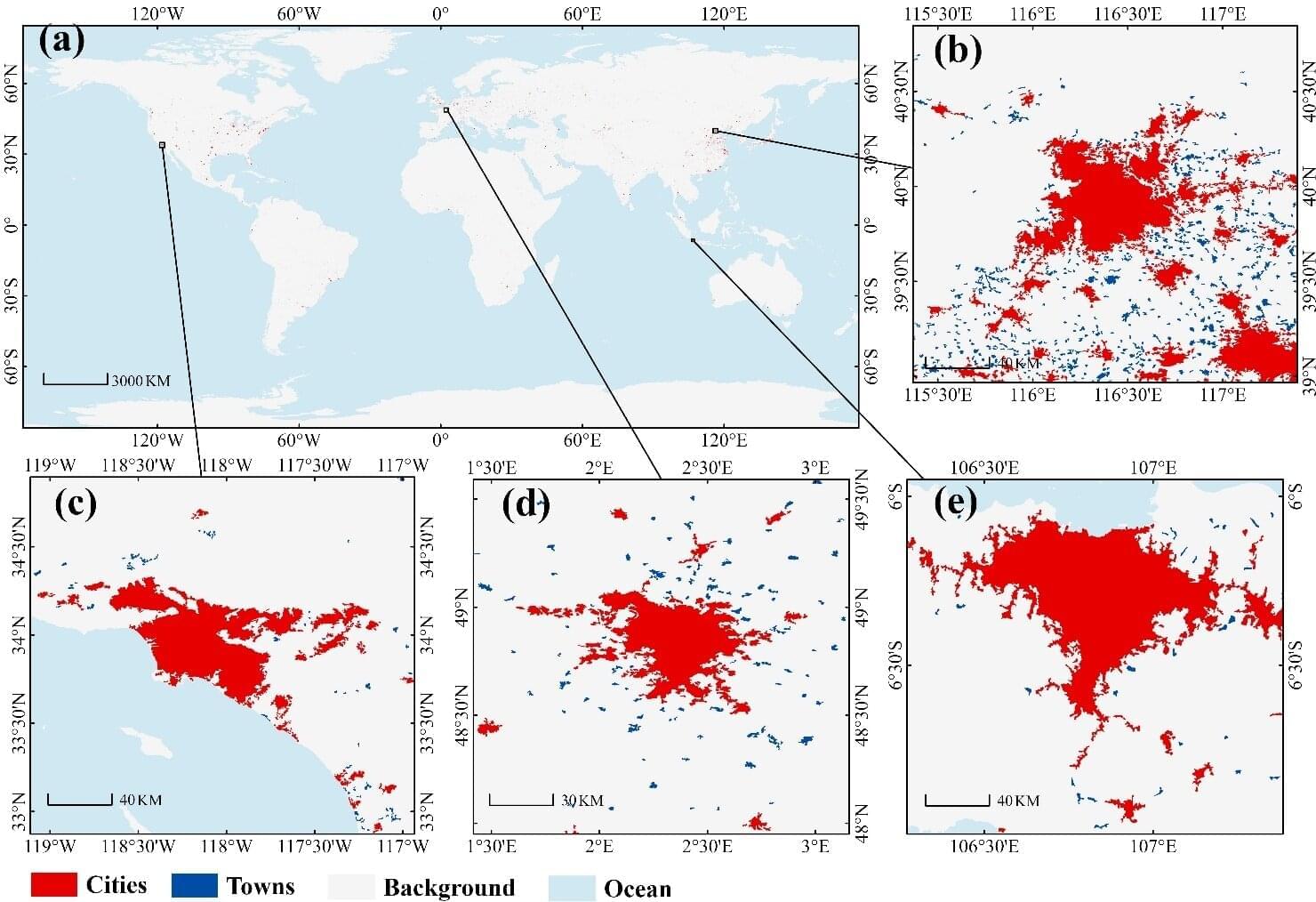

A research team led by Prof. Liu Liangyun from the Aerospace Information Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (AIRCAS) has produced the first comprehensive, high-resolution map of global city and town boundaries, offering a view of how urban boundaries have expanded and transformed over the past two decades. The new dataset—derived from 30-meter-resolution satellite observations—fills a long-standing gap in global urban studies.

Cities and towns are the dominant form of human settlement, playing a crucial role in sustaining ecological balance and advancing sustainable development. However, their complex spatial structures and rapid evolution have made high-resolution global urban boundary datasets scarce. To address this gap, the team integrated the GISD30 global impervious surface dynamic dataset with LandScan global population data to develop the Global City and Town Boundaries (GCTB) Dataset, which covers the period from 2000 to 2022.

Published in Scientific Data, the study details the researchers’ development of a morphology-oriented boundary delineation framework that combines kernel density estimation (KDE) and cellular automata (CA) to accurately map urban boundaries. When compared with multiple reference datasets, the GCTB Dataset showed the strongest agreement with the manually curated Atlas of Urban Expansion, achieving an R2 value of approximately 0.88—indicating high reliability in capturing urban extents.

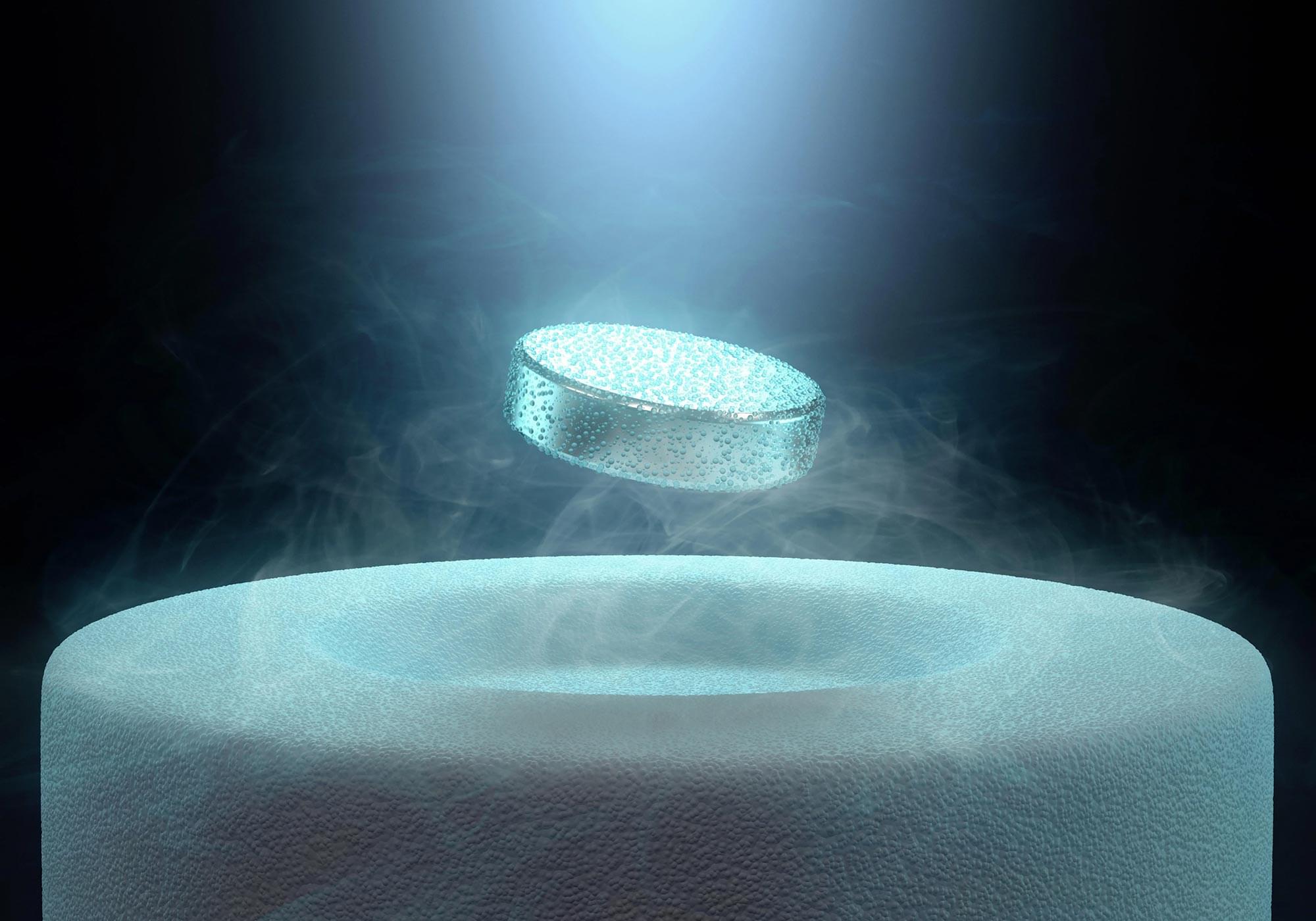

Superconductors are materials that allow electrical current to flow without any resistance, a property that typically appears only at extremely low temperatures. While most known superconductors follow established theoretical frameworks, strontium ruthenate, Sr₂RuO₄, has remained difficult to explain since researchers first identified its superconducting behavior in 1994.

The material is widely regarded as one of the purest and most thoroughly examined examples of unconventional superconductivity. Even so, scientists have not reached agreement on the exact nature of the electron pairing within Sr₂RuO₄, including its symmetry and internal structure, which are central to understanding how its superconductivity arises.

The threat actor behind two malicious browser extension campaigns, ShadyPanda and GhostPoster, has been attributed to a third attack campaign codenamed DarkSpectre that has impacted 2.2 million users of Google Chrome, Microsoft Edge, and Mozilla Firefox.

The activity is assessed to be the work of a Chinese threat actor that Koi Security is tracking under the moniker DarkSpectre. In all, the campaigns have collectively affected over 8.8 million users spanning a period of more than seven years.

ShadyPanda was first unmasked by the cybersecurity company earlier this month as targeting all three browser users to facilitate data theft, search query hijacking, and affiliate fraud. It has been found to affect 5.6 million users, including 1.3 newly identified victims stemming from over 100 extensions flagged as connected to the same cluster.

IBM has disclosed details of a critical security flaw in API Connect that could allow attackers to gain remote access to the application.

The vulnerability, tracked as CVE-2025–13915, is rated 9.8 out of a maximum of 10.0 on the CVSS scoring system. It has been described as an authentication bypass flaw.

“IBM API Connect could allow a remote attacker to bypass authentication mechanisms and gain unauthorized access to the application,” the tech giant said in a bulletin.