The U.S. Treasury has removed three individuals linked to Intellexa and Predator spyware from its sanctions list, without explaining the decision.

Grid storage batteries, for their part, collect excess power from various green energy sources, like wind farms. They can be charged and then discharged at times of higher demand and lower supply. Having plentiful, economical batteries is a key factor in pitching this kind of facility to nations and communities that are considering using renewables, or larger portions of renewables.

But setting up a mine to extract the massive deposit of lithium in Thacker Pass is not a simple task: it will require a wholly new process to separate the lithium from its natural clay deposit.

Lithium is all around us. The U.S. Geological Survey estimates there are 89 million tons of lithium in deposits on Earth, just two one-thousandths of 1 percent of Earth’s elemental abundance. Experts believe more than half of that lithium can be found in one triangular area of desert in western South America; but Thacker Pass in the United States, we now know, could contain as much as 40 million tons of lithium.

Best advice is simply disinfect with vinegar because it kills it on contact.

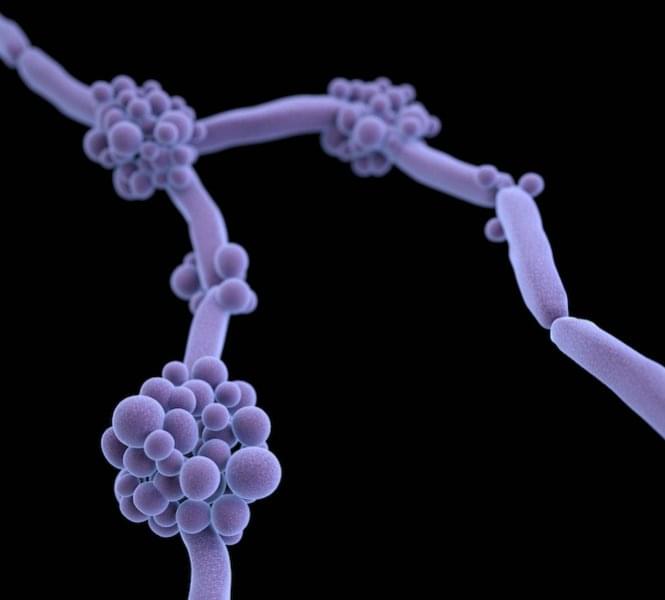

The fungal species Candida auris is spreading across the globe, and gaining in virulence, according to a new review by a Hackensack Meridian Center for Discovery and Innovation (CDI) scientist and colleagues.

But there are strategies available and underway to combat the invasive and drug-resistant germ, says the work in Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews.

The paper summarizes and analyzes the latest developments—and needs—in mycology in 2025. Neeraj Chauhan, Ph.D., of the CDI, is co-author with Anuradha Chowdhary, Ph.D., of the Medical Mycology Unit at the Vallabhbhai Patel Chest Institute at the University of Delhi, who is a global leader in identifying and combating fungal threats, and was one of the first scientists to identify C. auris as a major public health threat in India in 2014. Chowdhary is also a visiting researcher at the CDI.

Basically every year 1 billion people get infected by influenza causing extreme resource shortages still it is getting better to keep the death count down with vaccines but still its potential is still very dangerous and is not quite contained. Along with the super k version of influenza causing a spike in cases globally now. I still think that we need better protection against certain diseases so the resources are not drained globally. Perhaps we can use tricorder like devices on our phones that essentially heal us from diseases which I believe radio nanotransfection could lead to breakthroughs in the future.

Credit: WHO / Lindsay Mackenzie.

Influenza, or the flu, is both a seasonal and a pandemic virus. Every year, mainly during the winter season, seasonal influenza infects as many as 1 billion people. This makes it one of the most common infectious respiratory viruses, after the common cold. Thankfully, the WHO Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System, or GISRS, monitors what viruses are circulating and twice a year recommends which viruses to target in the flu vaccine for the upcoming season. The flu vaccine is the best way to prevent infection and may reduce symptoms if you do get the flu. For those who are more vulnerable to flu, what we call ‘high risk groups’, the vaccine can save your life. Good hygiene practices can also reduce the risk of infection (for more information, see the factsheet here ). Thankfully, although there are hundreds of millions of cases every year, the vast majority of these are not serious. Nevertheless, WHO estimates that there are 3 to 5 million cases of severe illness and between 290 000 to 650 000 respiratory deaths annually.

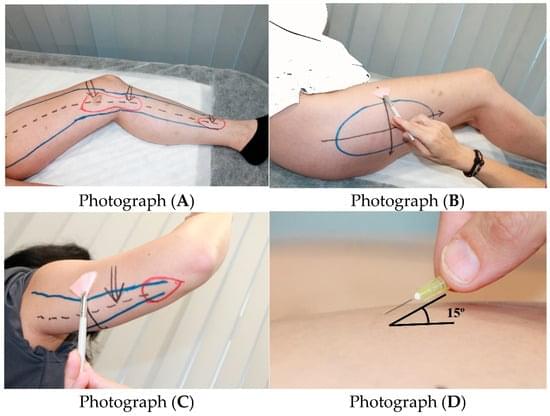

By Simarro Blasco, J. L., et al. (2025). Biomedicines, 13(12), 3049. 📖Read the full text: https://brnw.ch/21wYJvv.

Large clinical study of 1,800+ women with lipedema identifies key clinical signs and frequent comorbidities, supporting a systemic, connective-tissue–based understanding of the disease.

Background/Objectives: Lipedema is a chronic disorder that affects almost exclusively women and is characterized by bilateral, symmetrical accumulation of subcutaneous fat, typically in the buttocks, hips, and lower limbs, and in some cases the arms.

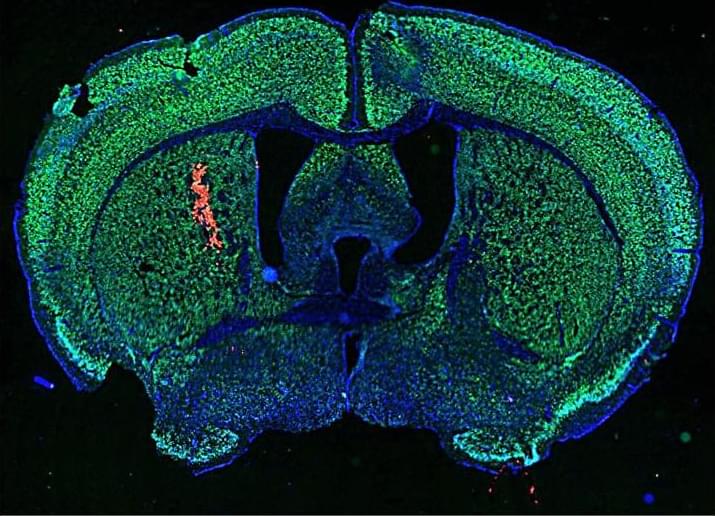

Harnessing antibodies found in patients with lupus, researchers test a new cancer therapy that turns autoimmune responses against tumor cells in mice, suggesting similar approaches could be integrated into immunotherapy regimens.

Learn more in Science Signaling.

Delivery of autoimmune disease–associated antibodies activates the immune system to fight glioblastomas.

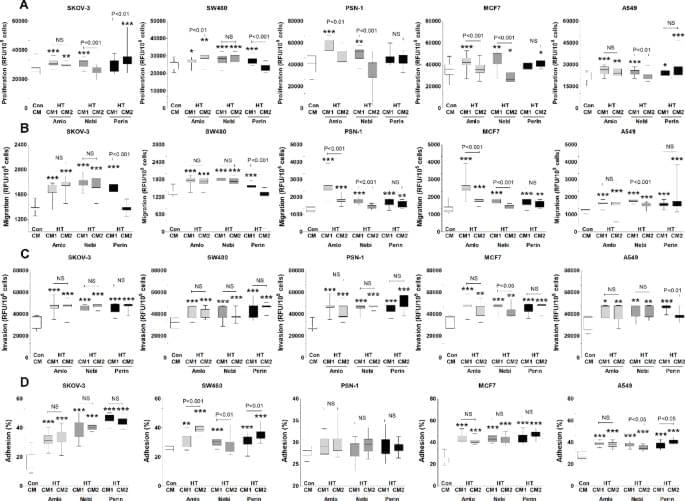

Uruski, P., Mikuła-Pietrasik, J., Tykarski, A. et al. Sci Rep 15, 43,463 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27414-x.

Cardiovascular risk factors can spark inflammation by eliciting misdirected responses of intrinsic vascular cells and leukocytes, culminating in lesion initiation, progression, and complication. Soehnlein and Libby review key underlying inflammatory mechanisms in atherosclerosis and discuss how new understanding based on increasingly sophisticated tools has enabled translation to the clinic.