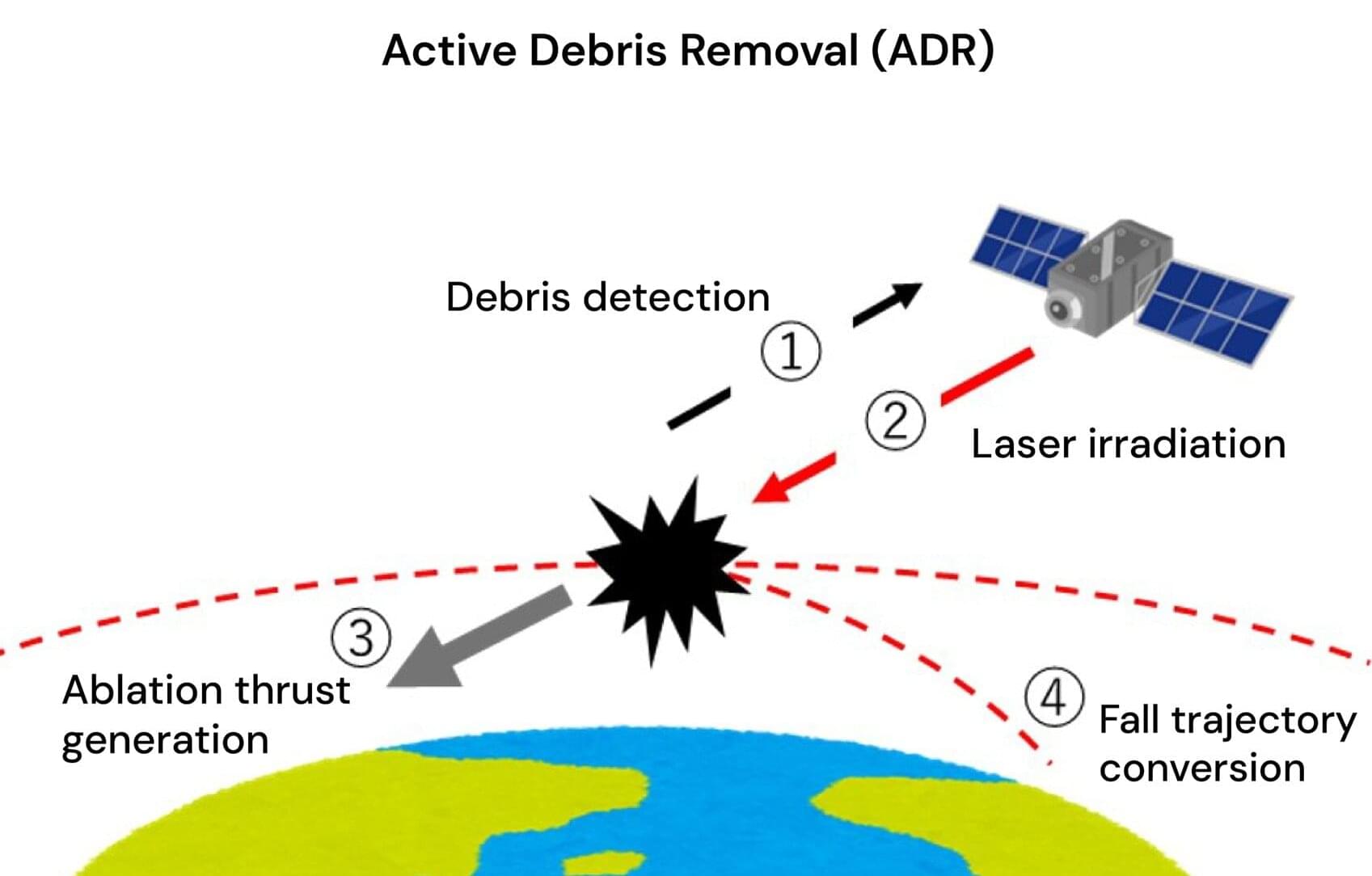

A possible alternative to active debris removal (ADR) by laser is ablative propulsion by a remotely transmitted electron beam (e-beam). The e-beam ablation has been widely used in industries, and it might provide higher overall energy efficiency of an ADR system and a higher momentum-coupling coefficient than laser ablation. However, transmitting an e-beam efficiently through the ionosphere plasma over a long distance (10 m–100 km) and focusing it to enhance its intensity above the ablation threshold of debris materials are new technical challenges that require novel methods of external actions to support the beam transmission.

Therefore, Osaka Metropolitan University researchers conducted a preliminary study of the relevant challenges, divergence, and instabilities of an e-beam in an ionospheric atmosphere, and identified them quantitatively through numerical simulations. Particle-in-cell simulations were performed systematically to clarify the divergence and the instability of an e-beam in an ionospheric plasma.

The major phenomena, divergence and instability, depended on the densities of the e-beam and the atmosphere. The e-beam density was set slightly different from the density of ionospheric plasma in the range from 1010 to 1012 m−3. The e-beam velocity was changed from 106 to 108 m/s, in a nonrelativistic range.