OpenAI will begin testing ads in ChatGPT for logged-in U.S. adults on free and Go tiers, stating ads won’t affect answers or sell user conversations.

Get the latest international news and world events from around the world.

Ingram Micro says ransomware attack affected 42,000 people

Information technology giant Ingram Micro has revealed that a ransomware attack on its systems in July 2025 led to a data breach affecting over 42,000 individuals.

Ingram Micro, one of the world’s largest business-to-business service providers and technology distributors, has over 23,500 associates, more than 161,000 customers, and reported net sales of $48 billion in 2024.

In data breach notification letters filed with Maine’s Attorney General and sent to those affected by the incident, the company said the attackers stole documents containing a wide range of personal information, including Social Security numbers.

Credential-stealing Chrome extensions target enterprise HR platforms

Malicious Chrome extensions on the Chrome Web Store masquerading as productivity and security tools for enterprise HR and ERP platforms were discovered stealing authentication credentials or blocking management pages used to respond to security incidents.

The campaign was discovered by cybersecurity firm Socket, which says it identified five Chrome extensions targeting Workday, NetSuite, and SAP SuccessFactors, collectively installed more than 2,300 times.

“The campaign deploys three distinct attack types: cookie exfiltration to remote servers, DOM manipulation to block security administration pages, and bidirectional cookie injection for direct session hijacking,” reports Socket.

Microsoft releases OOB Windows updates to fix shutdown, Cloud PC bugs

Microsoft has released multiple emergency, out-of-band updates for Windows 10, Windows 11, and Windows Server to fix two issues caused by the January Patch Tuesday updates.

The first issue impacts Windows 11, Windows 10, and Windows Server and blocks access to Microsoft 365 Cloud PC sessions. After installing the January 2026 security updates, some users may encounter credential prompt failures in remote connection applications.

“After installing the January 2026 Windows security update (the Originating KBs listed above), credential prompt failures might occur in some remote connection applications,” explained Microsoft.

Fake ad blocker extension crashes the browser for ClickFix attacks

A malvertising campaign is using a fake ad-blocking Chrome and Edge extension named NexShield that intentionally crashes the browser in preparation for ClickFix attacks.

The attacks were spotted earlier this month and delivered a new Python-based remote access tool called ModeloRAT that is deployed in corporate environments.

The NexShield extension, which has been removed from the Chrome Web Store, was promoted as a privacy-first, high-performance, lightweight ad blocker created by Raymond Hill, the original developer of the legitimate uBlock Origin ad blocker with more than 14 million users.

New PDFSider Windows malware deployed on Fortune 100 firm’s network

Ransomware attackers targeting a Fortune 100 company in the finance sector used a new malware strain, dubbed PDFSider, to deliver malicious payloads on Windows systems.

The attackers employed social engineering in their attempt to gain remote access by impersonating technical support workers and to trick company employees into installing Microsoft’s Quick Assist tool.

Researchers at cybersecurity company Resecurity found PDFSider during an incident response and describe it as a stealthy backdoor for long-term access, noting that it shows “characteristics commonly associated with APT tradecraft.”

Hacker admits to leaking stolen Supreme Court data on Instagram

A Tennessee man has pleaded guilty to hacking the U.S. Supreme Court’s electronic filing system and breaching accounts at the AmeriCorps U.S. federal agency and the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Federal prosecutors said that 24-year-old Nicholas Moore, of Springfield, Tennessee, had accessed the Supreme Court’s restricted electronic filing system at least 25 times between August and October 2023 using stolen credentials.

Additionally, he sometimes logged into the Supreme Court’s systems multiple times per day using the same compromised credentials.

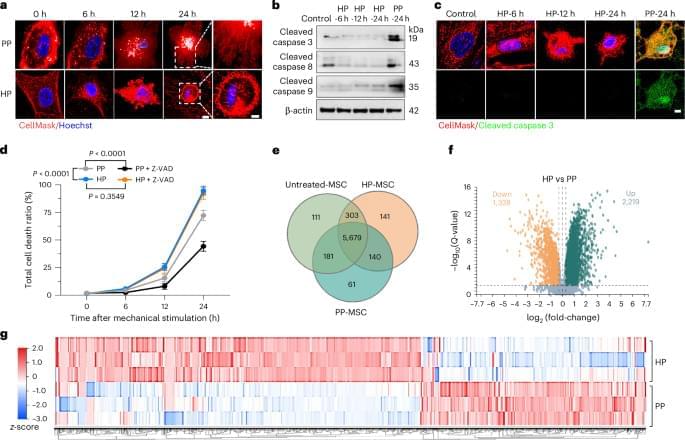

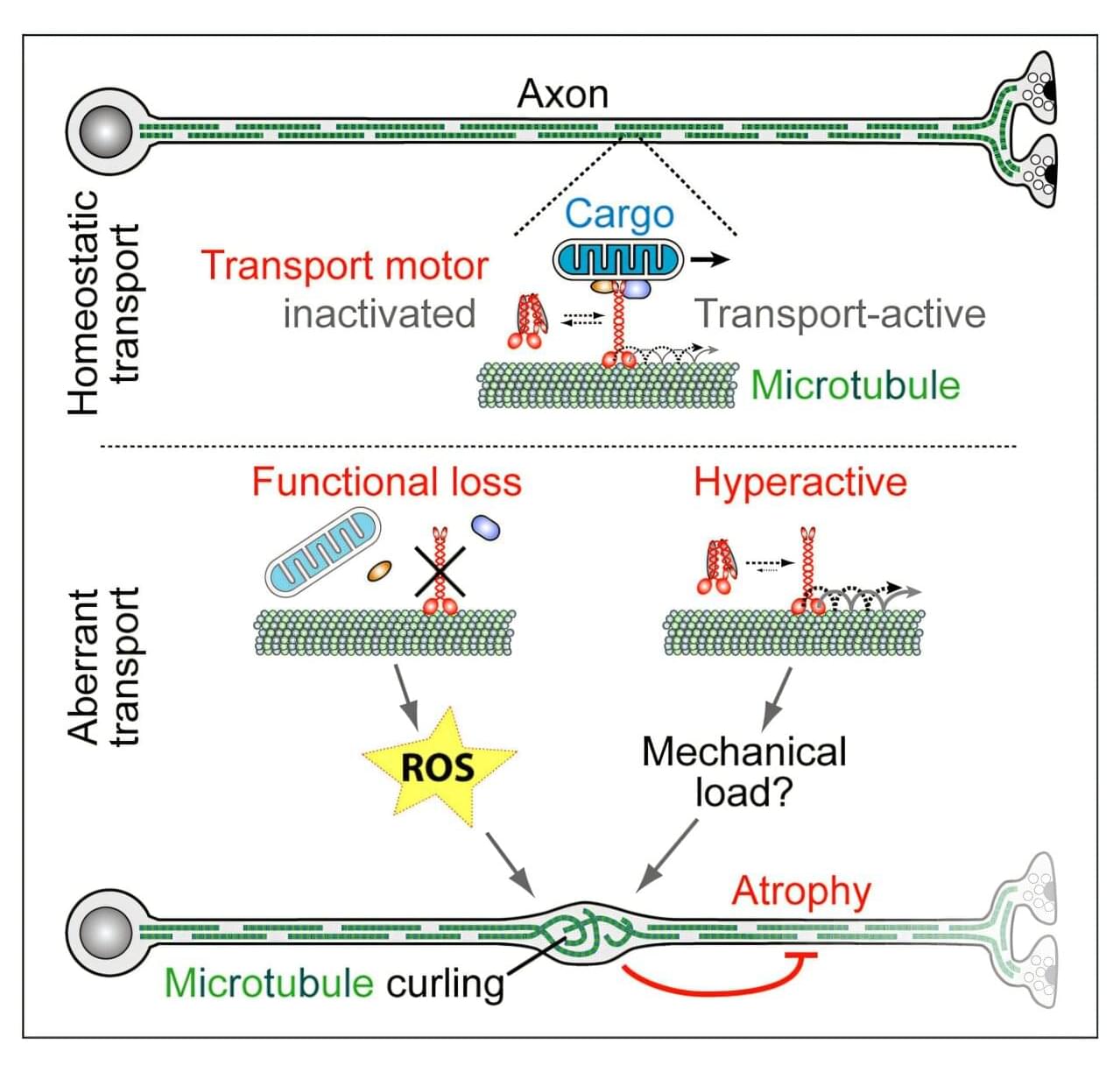

Motor protein discovery in fruit flies may unlock neurodegenerative secrets

Scientists have long known that inherited neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s or motor neuron disease, can be traced back to genetic mutations. However, how they cause the diseases remains unanswered.

In today’s issue of the journal Current Biology Professor Andreas Prokop revealed that so-called “motor proteins” can provide key answers in this quest.

The research by the Prokop group focuses on nerve fibers, also called axons. Axons are the delicate biological cables that send messages between the brain and body to control our movements and behavior. Intriguingly, axons need to survive and stay functional for our entire lifetime.