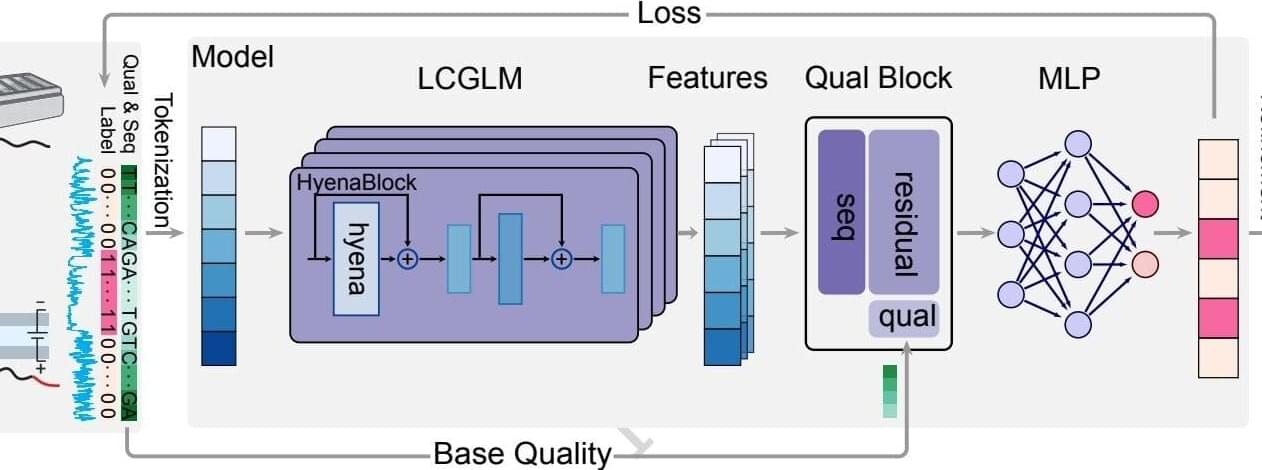

Scientists in the laboratory of Rendong Yang, Ph.D., associate professor of Urology, have developed a new large language model that can interpret transcriptomic data in cancer cell lines more accurately than conventional approaches, as detailed in a recent study published in Nature Communications.

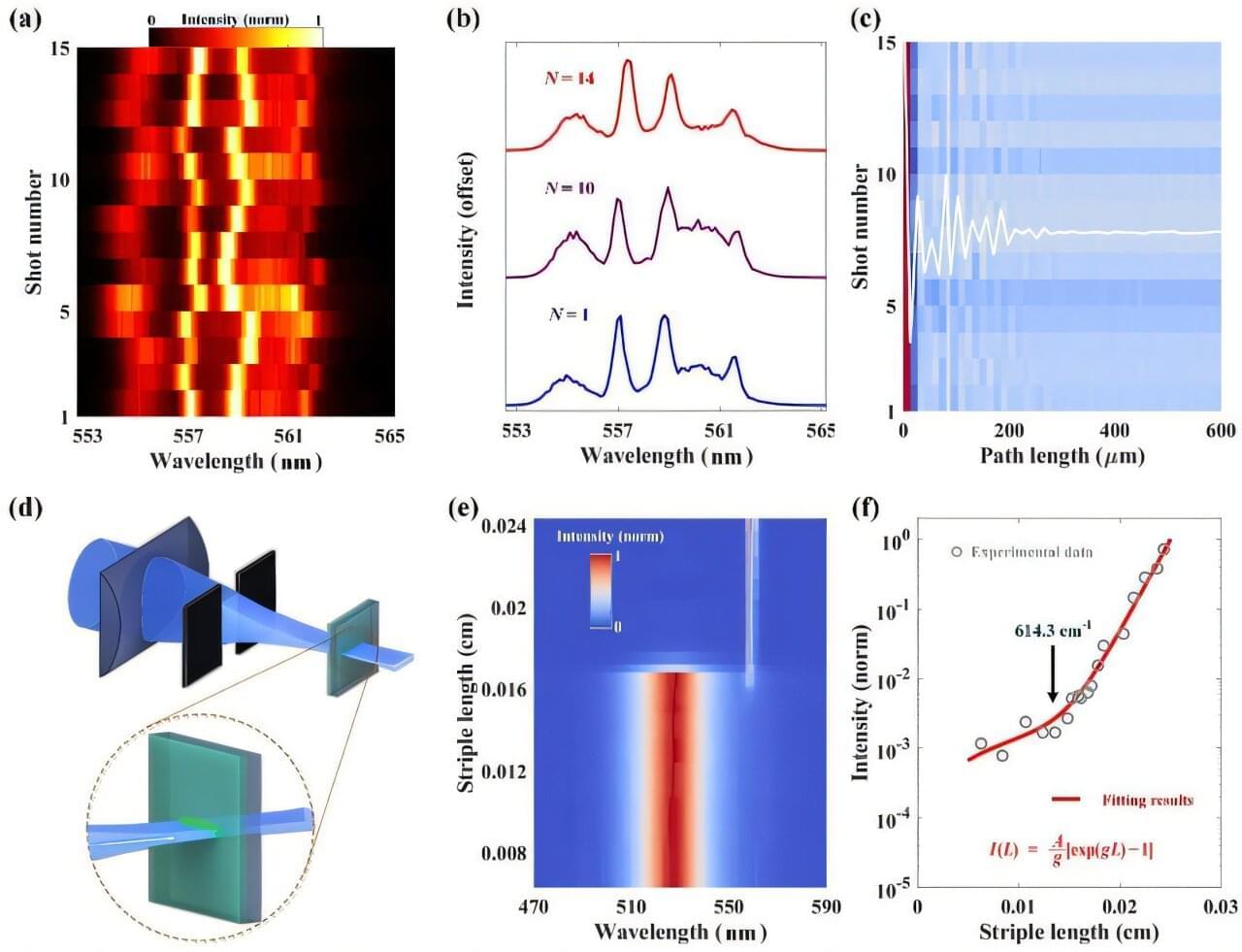

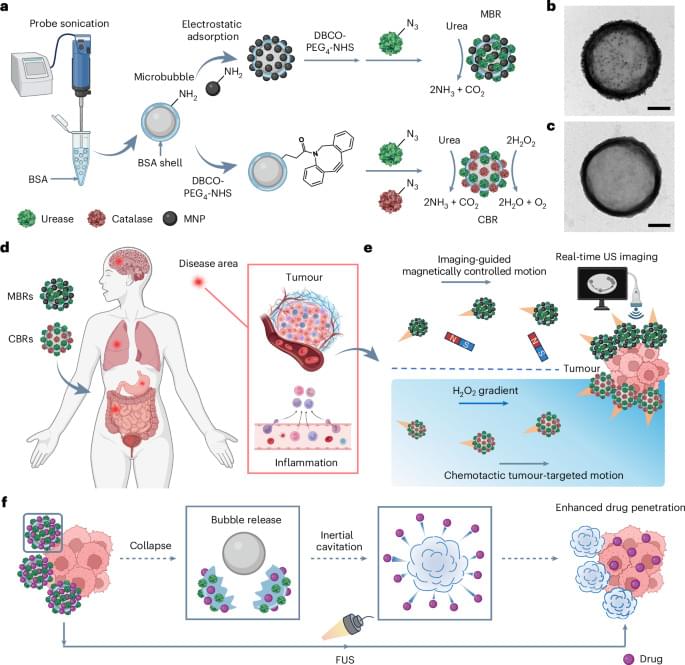

Long-read RNA sequencing technologies have transformed transcriptomics research by detecting complex RNA splicing and gene fusion events that have often been missed by conventional short-read RNA-sequencing methods.

Among these technologies includes nanopore direct RNA sequencing (dRNA-seq), which can sequence full-length RNA molecules directly and produce more accurate analyses of RNA biology. However, previous work suggests this approach may generate chimera artifacts—in which multiple RNA sequences incorrectly join to form a single RNA sequence—and limit the reliability and utility of the data.