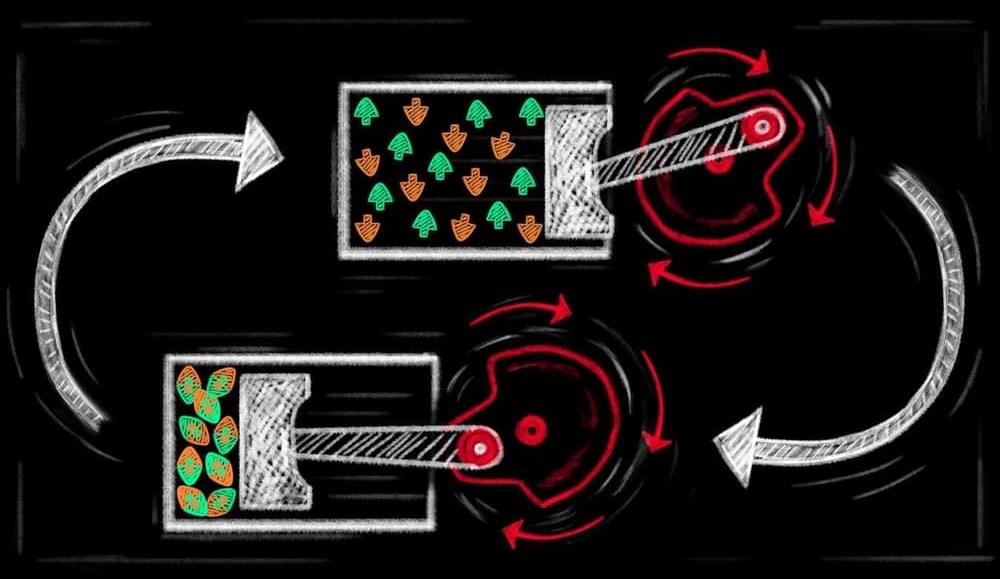

Researchers have turned an optical lattice into a ratchet that moves atoms from one site to the next.

The 2024 Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics goes to John Cardy and Alexander Zamolodchikov for their work in applying field theory to diverse problems.

Many physicists hear the words “quantum field theory,” and their thoughts turn to electrons, quarks, and Higgs bosons. In fact, the mathematics of quantum fields has been used extensively in other domains outside of particle physics for the past 40 years. The 2024 Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics has been awarded to two theorists who were instrumental in repurposing quantum field theory for condensed-matter, statistical physics, and gravitational studies.

“I really want to stress that quantum field theory is not the preserve of particle physics,” says John Cardy, a professor emeritus from the University of Oxford. He shares the Breakthrough Prize with Alexander Zamolodchikov from Stony Brook University, New York.

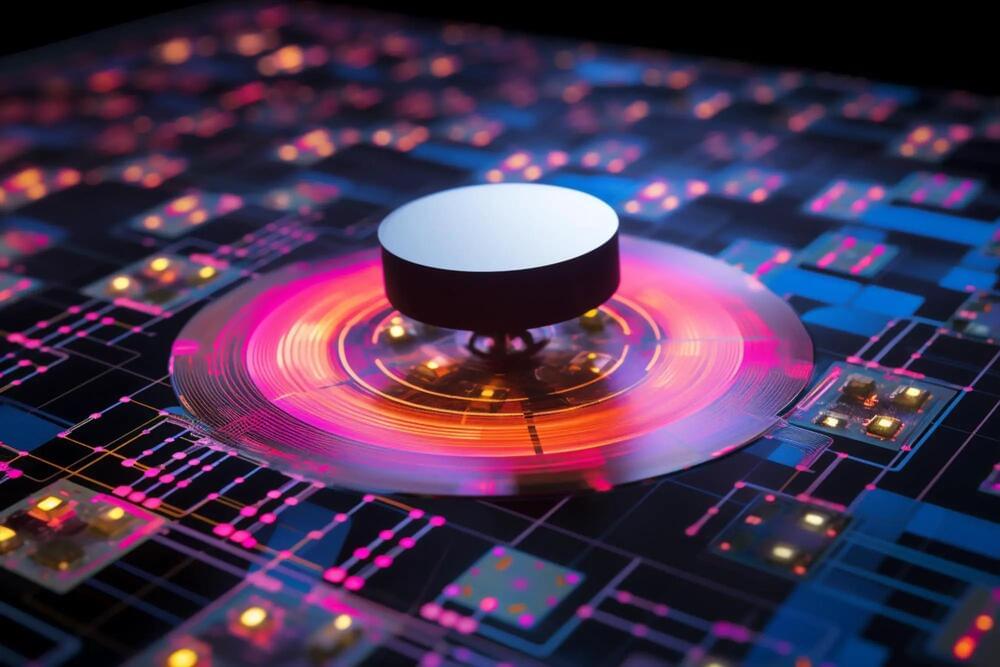

A complete quantum computing system could be as large as a two-car garage when one factors in all the paraphernalia required for smooth operation. But the entire processing unit, made of qubits, would barely cover the tip of your finger.

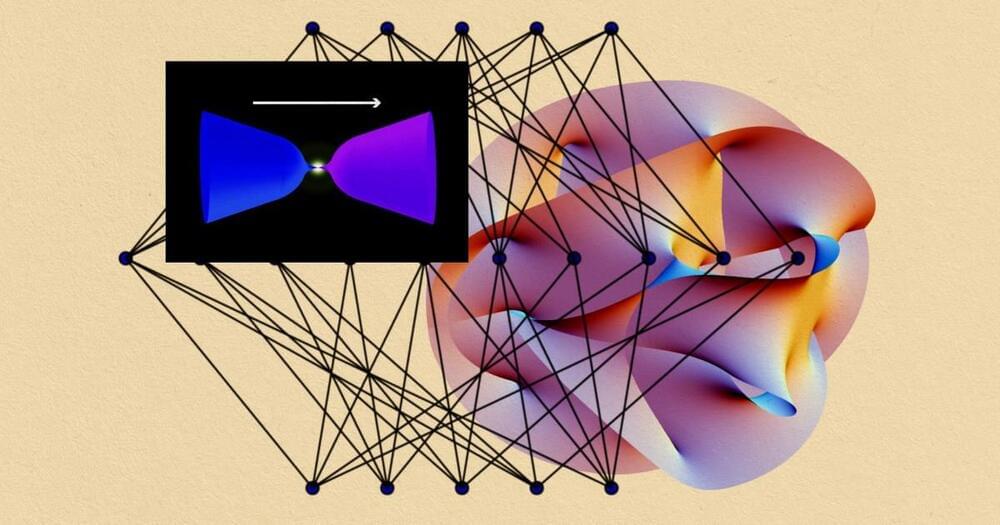

Today’s smartphones, laptops and supercomputers contain billions of tiny electronic processing elements called transistors that are either switched on or off, signifying a 1 or 0, the binary language computers use to express and calculate all information. Qubits are essentially quantum transistors. They can exist in two well-defined states—say, up and down—which represent the 1 and 0. But they can also occupy both of those states at the same time, which adds to their computing prowess. And two—or more—qubits can be entangled, a strange quantum phenomenon where particles’ states correlate even if the particles lie across the universe from each other. This ability completely changes how computations can be carried out, and it is part of what makes quantum computers so powerful, says Nathalie de Leon, a quantum physicist at Princeton University. Furthermore, simply observing a qubit can change its behavior, a feature that de Leon says might create even more of a quantum benefit. “Qubits are pretty strange. But we can exploit that strangeness to develop new kinds of algorithms that do things classical computers can’t do,” she says.

Scientists are trying a variety of materials to make qubits. They range from nanosized crystals to defects in diamond to particles that are their own antiparticles. Each comes with pros and cons. “It’s too early to call which one is the best,” says Marina Radulaski of the University of California, Davis. De Leon agrees. Let’s take a look.

A quantum engine that works by toggling the properties of an ultracold atom cloud could one day be used to charge quantum batteries.

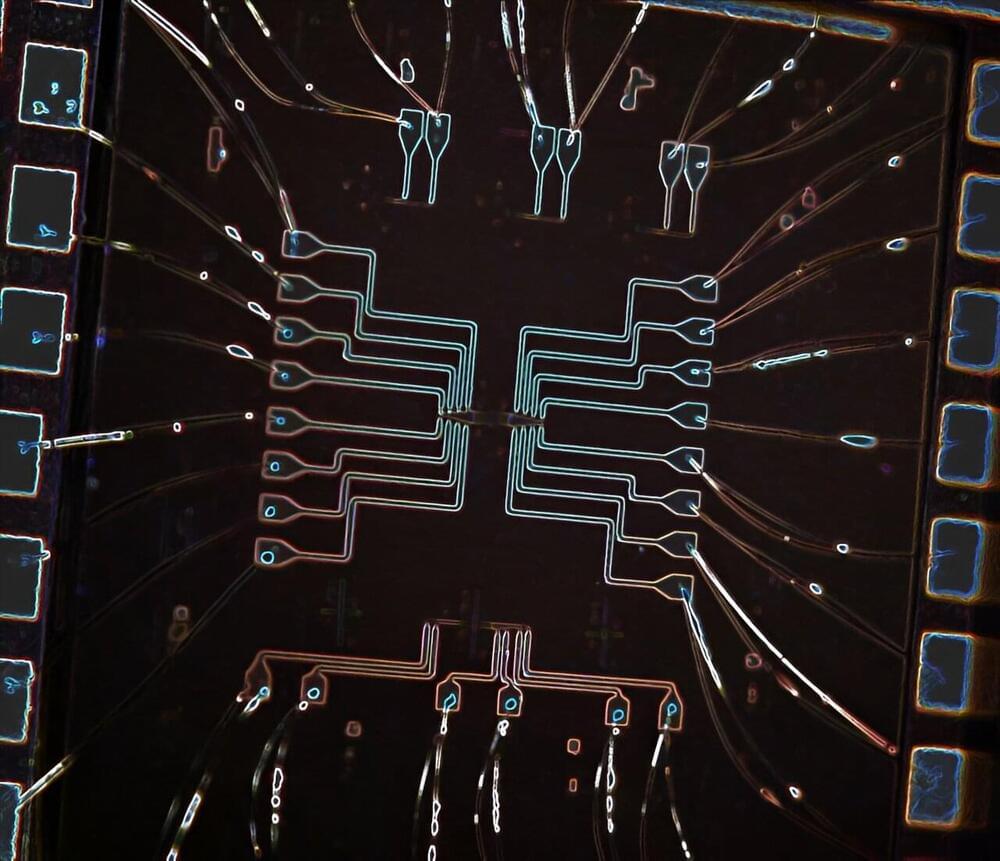

Advance lays the groundwork for miniature devices for spectroscopy, communications, and quantum computing. Researchers have created chip-based photonic resonators that operate in the ultraviolet (UV) and visible regions of the spectrum and exhibit a record low UV light loss. The new resonators lay the groundwork for increasing the size, complexity, and fidelity of UV photonic integrated circuit (PIC) design, which could enable new miniature chip-based devices for applications such as spectroscopic sensing, underwater communication, and quantum information processing.

Today, we are living in the midst of a race to develop a quantum computer, one that could be used for practical applications. This device, built on the principles of quantum mechanics, holds the potential to perform computing tasks far beyond the capabilities of today’s fastest supercomputers. Quantum computers and other quantum-enabled technologies could foster significant advances in areas such as cybersecurity and molecular simulation, impacting and even revolutionizing fields such as online security, drug discovery and material fabrication.

An offshoot of this technological race is building what is known in scientific and engineering circles as a “quantum simulator”—a special type of quantum computer, constructed to solve one equation model for a specific purpose beyond the computing power of a standard computer. For example, in medical research, a quantum simulator could theoretically be built to help scientists simulate a specific, complex molecular interaction for closer study, deepening scientific understanding and speeding up drug development.

But just like building a practical, usable quantum computer, constructing a useful quantum simulator has proven to be a daunting challenge. The idea was first proposed by mathematician Yuri Manin in 1980. Since then, researchers have attempted to employ trapped ions, cold atoms and superconducting qubits to build a quantum simulator capable of real-world applications, but to date, these methods are all still a work in progress.

Quantum technology holds immense promise, yet it is riddled with complexity. Anticipated to usher in a slew of technological advancements in the upcoming decades, it is set to offer us more compact and accurate sensors, robustly secure communication networks, and high-capacity computers. These advancements will outpace the capabilities of present computing technologies, aiding in the swift development of new drugs and materials, controlling financial markets, and enhancing weather forecasting.

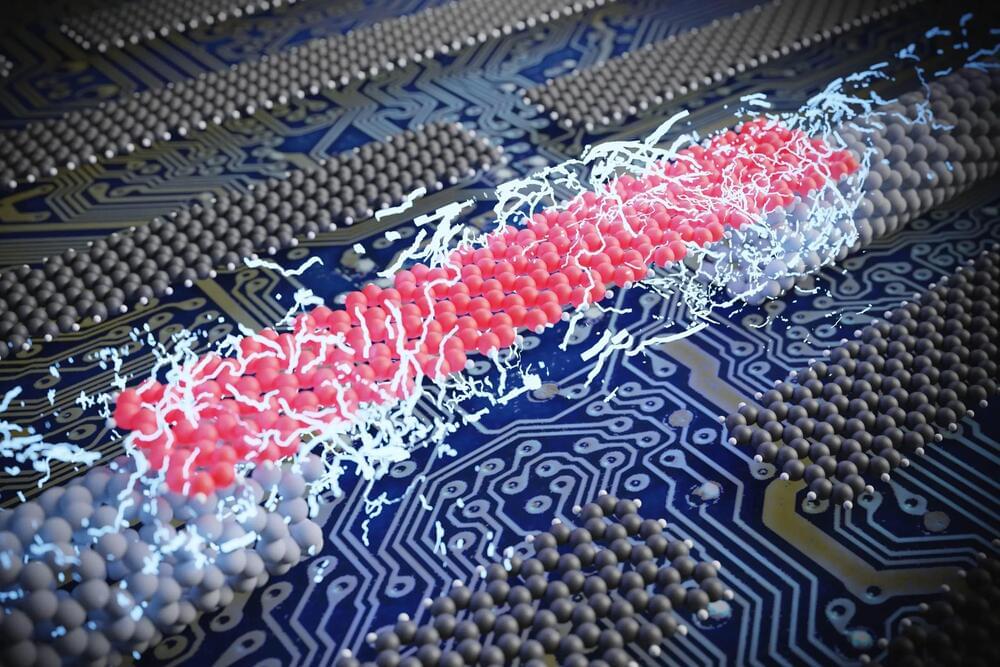

To realize these benefits, we require what are termed as quantum materials, which display significant quantum physical effects. One such material is graphene.

Graphene is an allotrope of carbon in the form of a single layer of atoms in a two-dimensional hexagonal lattice in which one atom forms each vertex. It is the basic structural element of other allotropes of carbon, including graphite, charcoal, carbon nanotubes, and fullerenes. In proportion to its thickness, it is about 100 times stronger than the strongest steel.

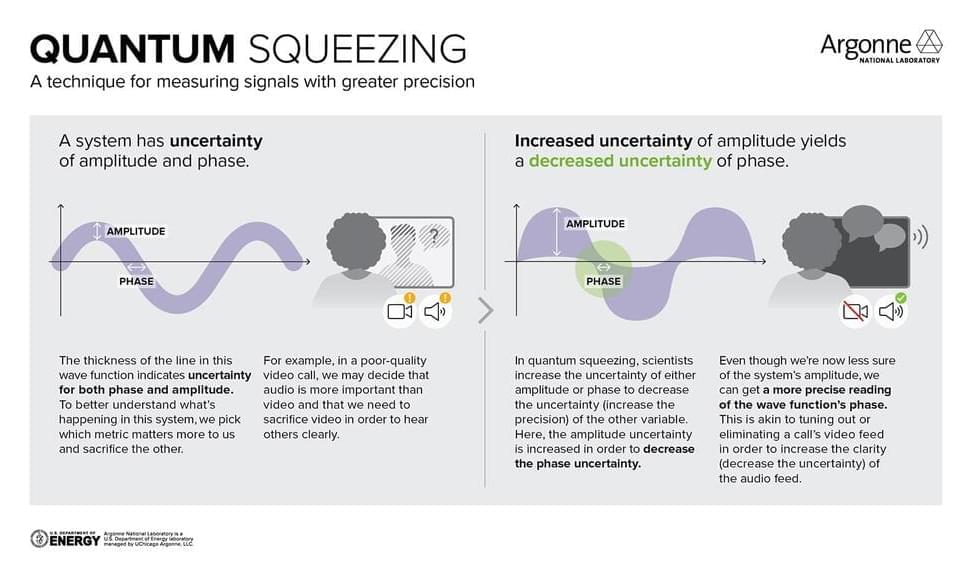

How many times have you shown up to a video meeting with people at work only to find you have terrible internet that day? Maybe the others on the call are cutting in and out, or maybe your own signal is being corrupted on their screen. Regardless, many remote workers have found a simple solution—turn down the video quality and focus on audio.

In a very general sense, this is the same technique that researchers leverage when using quantum squeezing to improve the performance of their sensors. Mark Kasevich, a professor of physics and applied physics at Stanford University and a member of Q-NEXT, uses quantum squeezing in his work developing quantum sensors.

Q-NEXT is a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) National Quantum Information Science Research Center led by DOE’s Argonne National Laboratory. Center researchers use quantum squeezing to make better measurements of quantum systems.

In the future, quantum computers may be able to solve problems that are far too complex for today’s most powerful supercomputers. To realize this promise, quantum versions of error correction codes must be able to account for computational errors faster than they occur.

However, today’s quantum computers are not yet robust enough to realize such error correction at commercially relevant scales.

On the way to overcoming this roadblock, MIT researchers demonstrated a novel superconducting qubit architecture that can perform operations between qubits—the building blocks of a quantum computer—with much greater accuracy than scientists have previously been able to achieve.