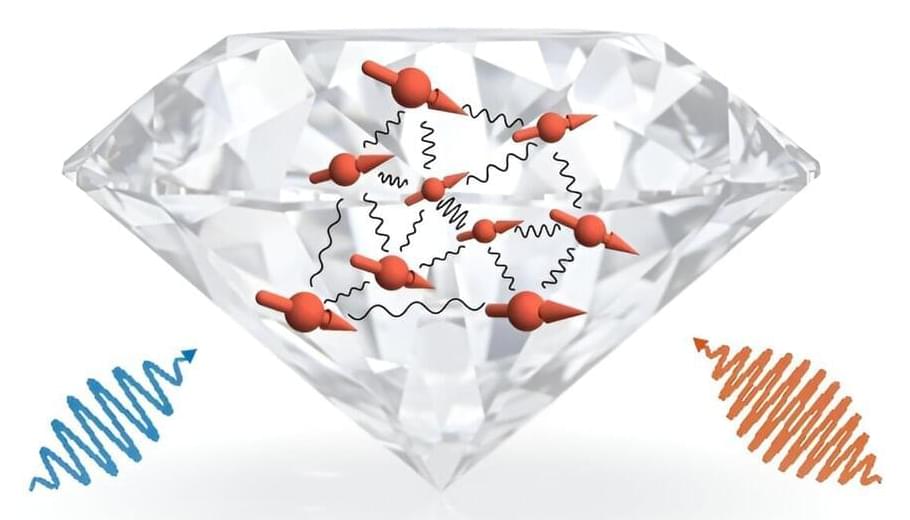

Quantum entanglement is one of the most astonishing properties of quantum mechanics. If two particles are entangled, the state of one particle cannot be described independently from the other. This is a unique property of the quantum world and forms a crucial difference between classical and quantum theories of physics. It is so important, the 2022 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Alain Aspect, John F. Clauser and Anton Zeilinger “for experiments with entangled photons, establishing the violation of Bell inequalities and pioneering quantum information science”.

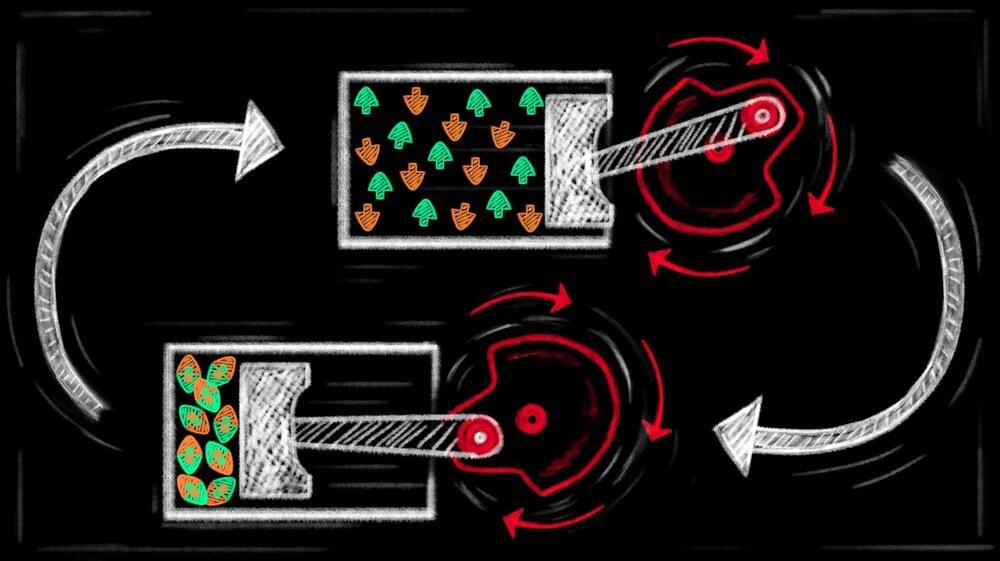

The large mass of the top quark, which is greater than any other particle, remains one of the most enduring mysteries of the Standard Model. Why this is so remains unexplained, however, the top quark has many unique properties to exploit as a result. The top quark is so heavy that it is extremely unstable and decays before it has time to hadronise, transferring all of its quantum numbers to its decay particles. Physicists can detect these decay particles and thus reconstruct the quantum state of a top quark, a feat that is impossible with any other quark. Most importantly, they can measure its spin and use it to show that entanglement can be studied in top-quark-pair production at the LHC.

Entanglement has indeed been measured in the past, but not quite like this. Most previous entanglement measurements involved low non-relativistic energies, typically utilising photons or electrons. The LHC collides protons with an incredibly high centre-of-mass energy. The data used in ATLAS’ new measurement were obtained from collisions at 13 TeV collected between 2015 and 2018. This means researchers are delving into an energy scale over 12 orders of magnitude (a thousand billion times) higher than typical laboratory experiments.