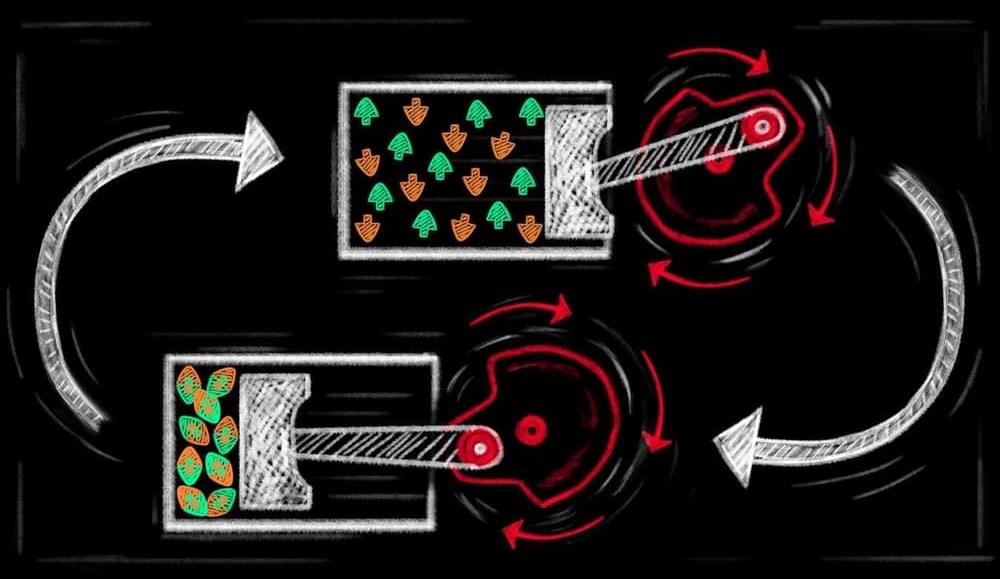

A quantum engine that works by toggling the properties of an ultracold atom cloud could one day be used to charge quantum batteries.

A quantum engine that works by toggling the properties of an ultracold atom cloud could one day be used to charge quantum batteries.

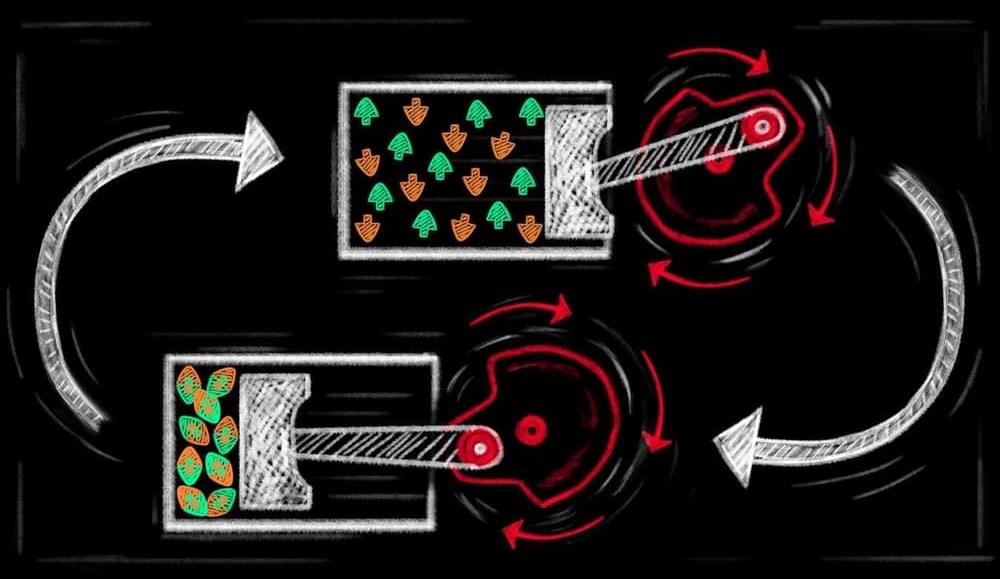

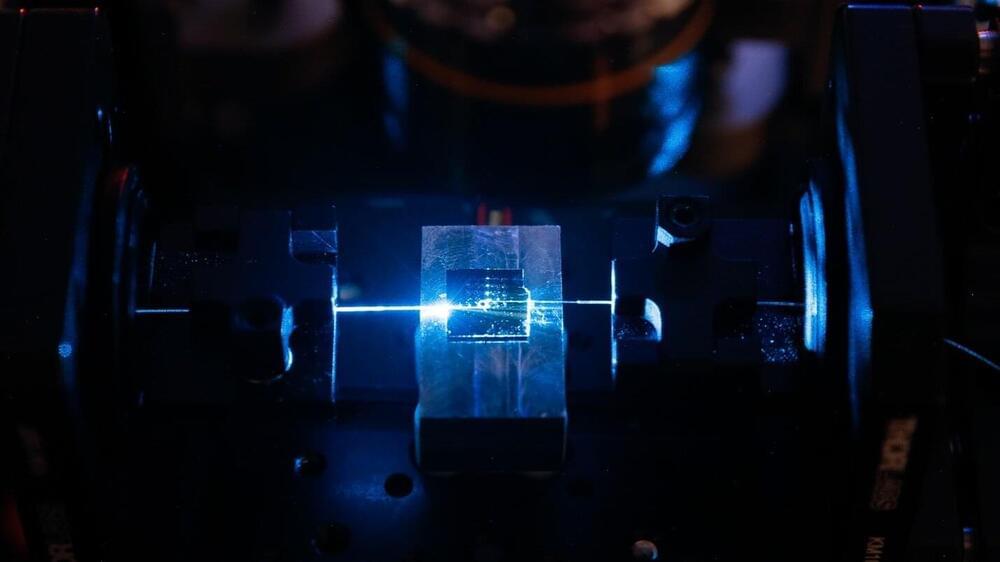

Advance lays the groundwork for miniature devices for spectroscopy, communications, and quantum computing. Researchers have created chip-based photonic resonators that operate in the ultraviolet (UV) and visible regions of the spectrum and exhibit a record low UV light loss. The new resonators lay the groundwork for increasing the size, complexity, and fidelity of UV photonic integrated circuit (PIC) design, which could enable new miniature chip-based devices for applications such as spectroscopic sensing, underwater communication, and quantum information processing.

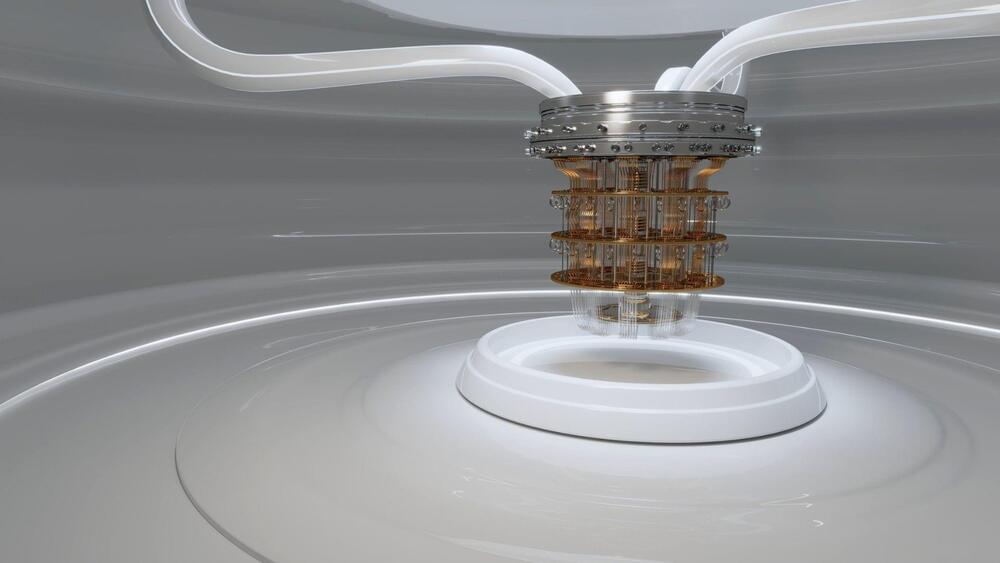

Today, we are living in the midst of a race to develop a quantum computer, one that could be used for practical applications. This device, built on the principles of quantum mechanics, holds the potential to perform computing tasks far beyond the capabilities of today’s fastest supercomputers. Quantum computers and other quantum-enabled technologies could foster significant advances in areas such as cybersecurity and molecular simulation, impacting and even revolutionizing fields such as online security, drug discovery and material fabrication.

An offshoot of this technological race is building what is known in scientific and engineering circles as a “quantum simulator”—a special type of quantum computer, constructed to solve one equation model for a specific purpose beyond the computing power of a standard computer. For example, in medical research, a quantum simulator could theoretically be built to help scientists simulate a specific, complex molecular interaction for closer study, deepening scientific understanding and speeding up drug development.

But just like building a practical, usable quantum computer, constructing a useful quantum simulator has proven to be a daunting challenge. The idea was first proposed by mathematician Yuri Manin in 1980. Since then, researchers have attempted to employ trapped ions, cold atoms and superconducting qubits to build a quantum simulator capable of real-world applications, but to date, these methods are all still a work in progress.

Quantum technology holds immense promise, yet it is riddled with complexity. Anticipated to usher in a slew of technological advancements in the upcoming decades, it is set to offer us more compact and accurate sensors, robustly secure communication networks, and high-capacity computers. These advancements will outpace the capabilities of present computing technologies, aiding in the swift development of new drugs and materials, controlling financial markets, and enhancing weather forecasting.

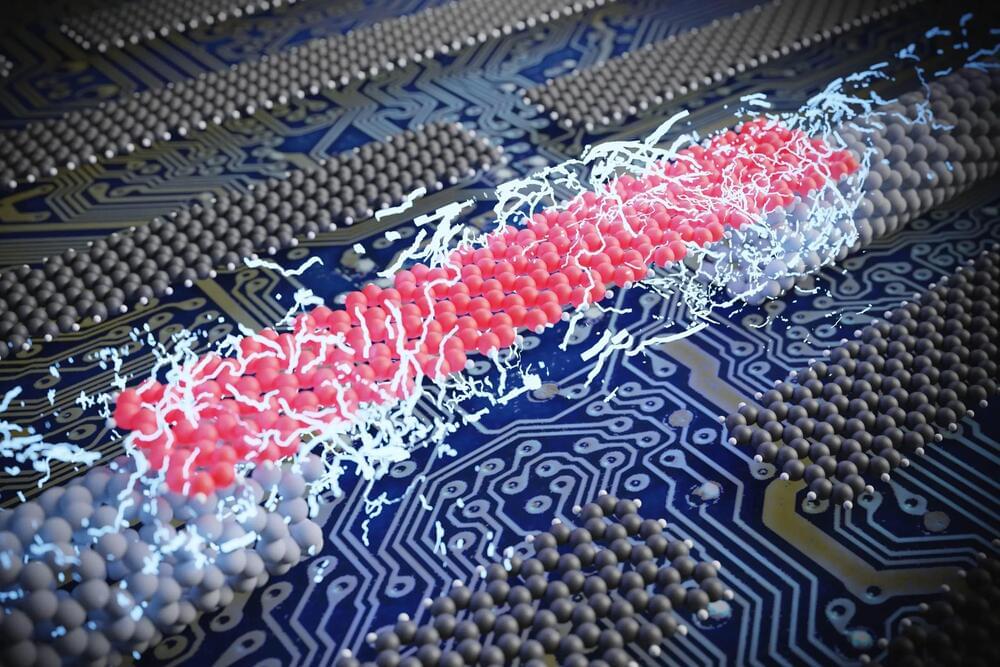

To realize these benefits, we require what are termed as quantum materials, which display significant quantum physical effects. One such material is graphene.

Graphene is an allotrope of carbon in the form of a single layer of atoms in a two-dimensional hexagonal lattice in which one atom forms each vertex. It is the basic structural element of other allotropes of carbon, including graphite, charcoal, carbon nanotubes, and fullerenes. In proportion to its thickness, it is about 100 times stronger than the strongest steel.

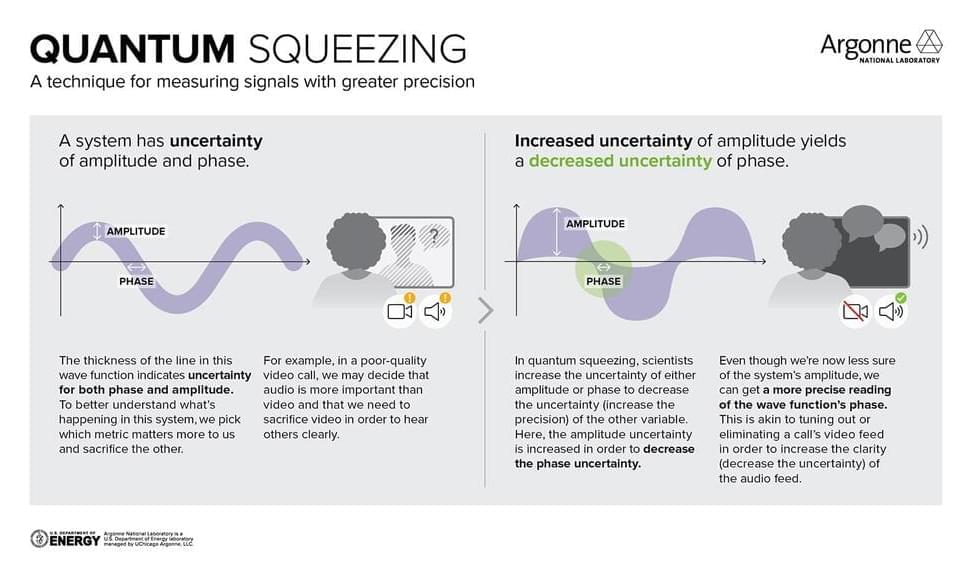

How many times have you shown up to a video meeting with people at work only to find you have terrible internet that day? Maybe the others on the call are cutting in and out, or maybe your own signal is being corrupted on their screen. Regardless, many remote workers have found a simple solution—turn down the video quality and focus on audio.

In a very general sense, this is the same technique that researchers leverage when using quantum squeezing to improve the performance of their sensors. Mark Kasevich, a professor of physics and applied physics at Stanford University and a member of Q-NEXT, uses quantum squeezing in his work developing quantum sensors.

Q-NEXT is a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) National Quantum Information Science Research Center led by DOE’s Argonne National Laboratory. Center researchers use quantum squeezing to make better measurements of quantum systems.

In the future, quantum computers may be able to solve problems that are far too complex for today’s most powerful supercomputers. To realize this promise, quantum versions of error correction codes must be able to account for computational errors faster than they occur.

However, today’s quantum computers are not yet robust enough to realize such error correction at commercially relevant scales.

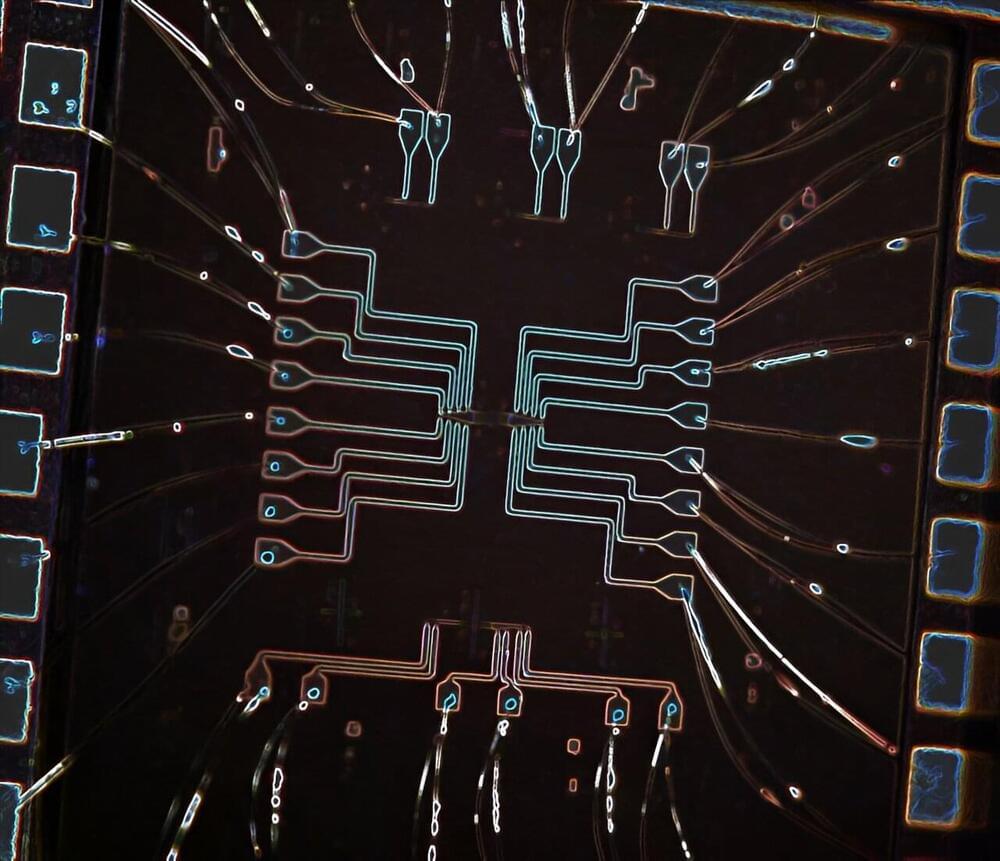

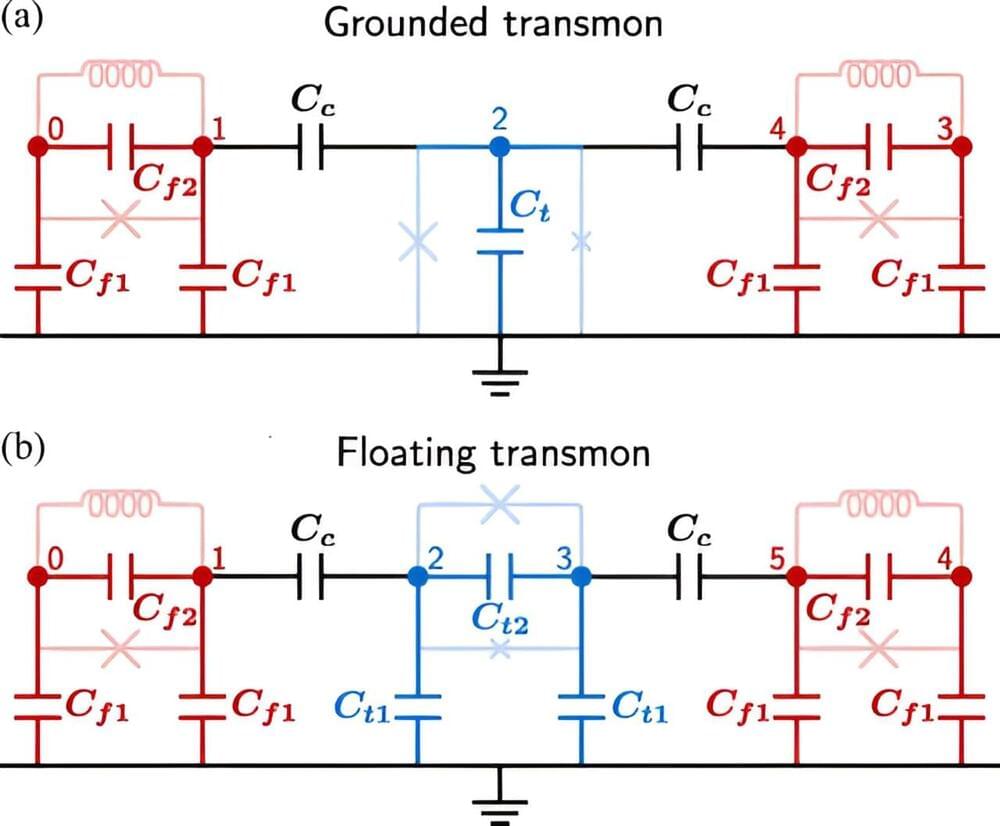

On the way to overcoming this roadblock, MIT researchers demonstrated a novel superconducting qubit architecture that can perform operations between qubits—the building blocks of a quantum computer—with much greater accuracy than scientists have previously been able to achieve.

Researchers have created chip-based photonic resonators that operate in the ultraviolet (UV) and visible regions of the spectrum and exhibit a record low UV light loss. The new resonators lay the groundwork for increasing the size, complexity and fidelity of UV photonic integrated circuit (PIC) design, which could enable new miniature chip-based devices for applications such as spectroscopic sensing, underwater communication and quantum information processing.

“Compared to the better-established fields like telecom photonics and visible photonics, UV photonics is less explored even though UV wavelengths are needed to access certain atomic transitions in atom/ion-based quantum computing and to excite certain fluorescent molecules for biochemical sensing,” said research team member Chengxing He from Yale University. “Our work sets a good basis toward building photonic circuits that operate at UV wavelengths.”

In Optics Express, the researchers describe the alumina-based optical microresonators and how they achieved an unprecedented low loss at UV wavelengths by combining the right material with optimized design and fabrication.

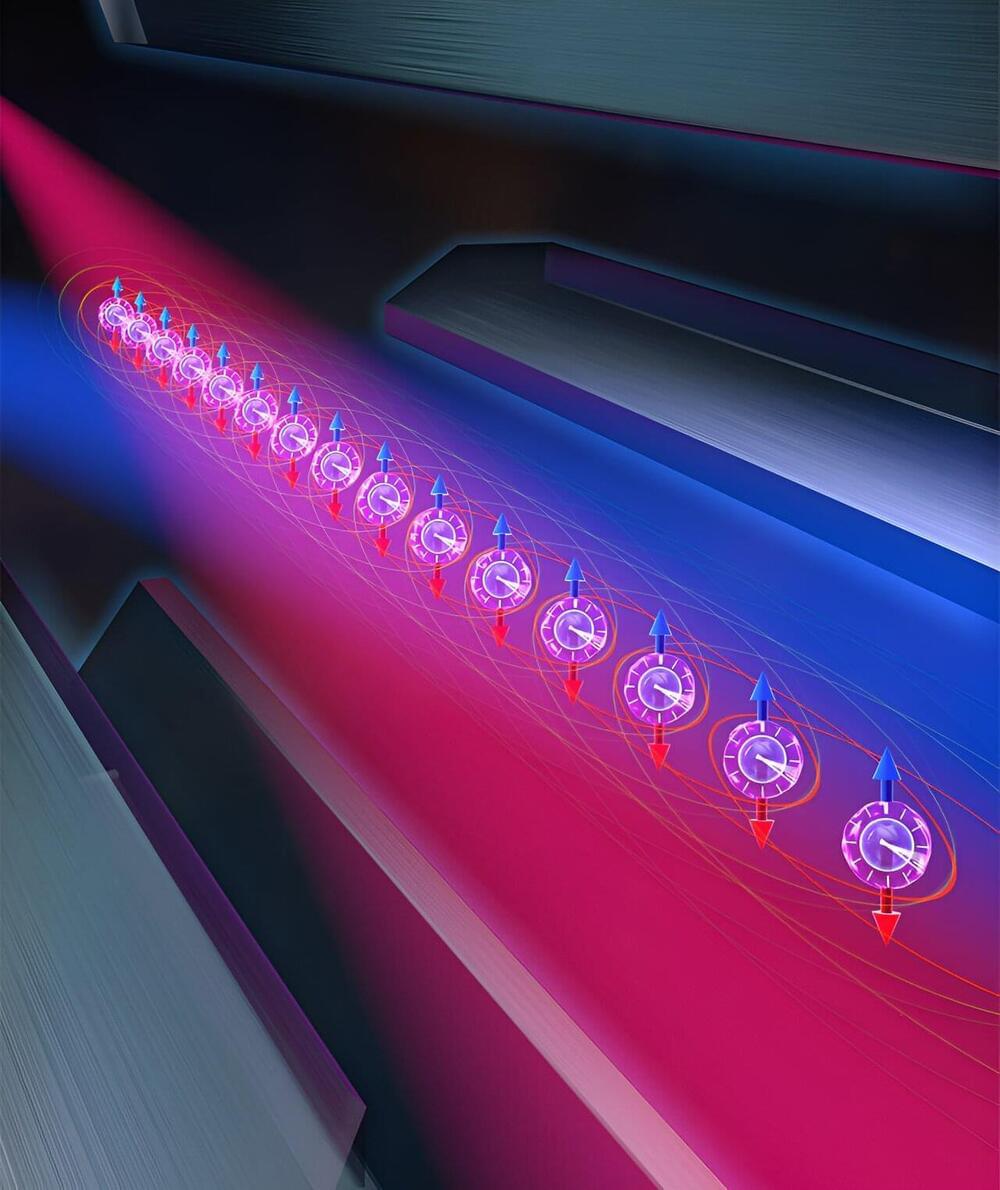

Opening new possibilities for quantum sensors, atomic clocks and tests of fundamental physics, JILA researchers have developed new ways of “entangling” or interlinking the properties of large numbers of particles. In the process they have devised ways to measure large groups of atoms more accurately even in disruptive, noisy environments.

The new techniques are described in a pair of papers published in Nature. JILA is a joint institute of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the University of Colorado Boulder.

“Entanglement is the holy grail of measurement science,” said Ana Maria Rey, a theoretical physicist and a JILA and NIST Fellow. “Atoms are the best sensors ever. They’re universal. The problem is that they’re quantum objects, so they’re intrinsically noisy. When you measure them, sometimes they’re in one energy state, sometimes they’re in another state. When you entangle them, you can manage to cancel the noise.”

The team achieved 99.99 percent accuracy with a single-qubit gate and 99.9 percent accuracy with a two-qubit gate.

Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have developed a new circuit that can do quantum computation with a high degree of accuracy. The researchers used a new type of superconducting qubit called the fluxonium, a press release said.

Quantum computers are considered the next frontier of computing since they can perform calculations at speeds that are decades ahead of supercomputers being used today. The flip side of such high speeds is that they can accumulate errors equally fast.