Quantum computing is drawing more attention now than generative AI did before ChatGPT’s release. This sparks big questions about what QC could achieve in 2025.

Even so, many wonder: If the universe is at bottom deterministic (via stable laws of physics), how do these quantum-like phenomena arise, and could they show up in something as large and complex as the human brain?

Quantum-Prime Computing is a new theoretical framework offering a surprising twist: it posits that prime numbers — often celebrated as the “building blocks” of integers — can give rise to “quantum-like” behavior in a purely mathematical or classical environment. The kicker? This might not only shift how we view computation but also hint at new ways to understand the brain and the nature of consciousness.

Below, we explore why prime numbers are so special, how they can host quantum-like states, and what that might mean for free will, consciousness, and the future of computational science.

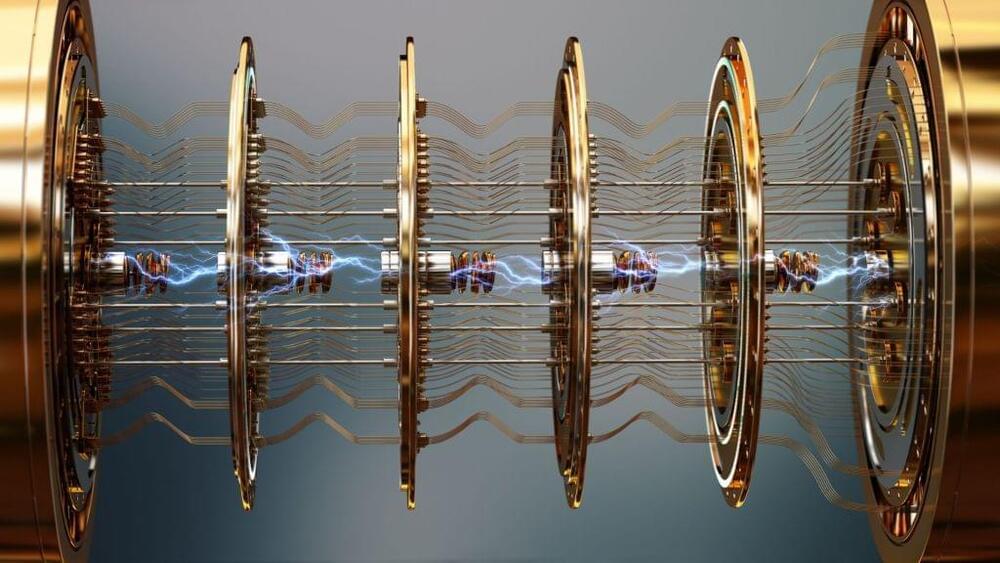

Theoretical physicists predict the existence of exotic “paraparticles” that defy classification and could have quantum computing applications.

By Davide Castelvecchi & Nature magazine

Theoretical physicists have proposed the existence of a new type of particle that doesn’t fit into the conventional classifications of fermions and bosons. Their ‘paraparticle’, described in Nature on January 8, is not the first to be suggested, but the detailed mathematical model characterizing it could lead to experiments in which it is created using a quantum computer. The research also suggests that undiscovered elementary paraparticles might exist in nature.

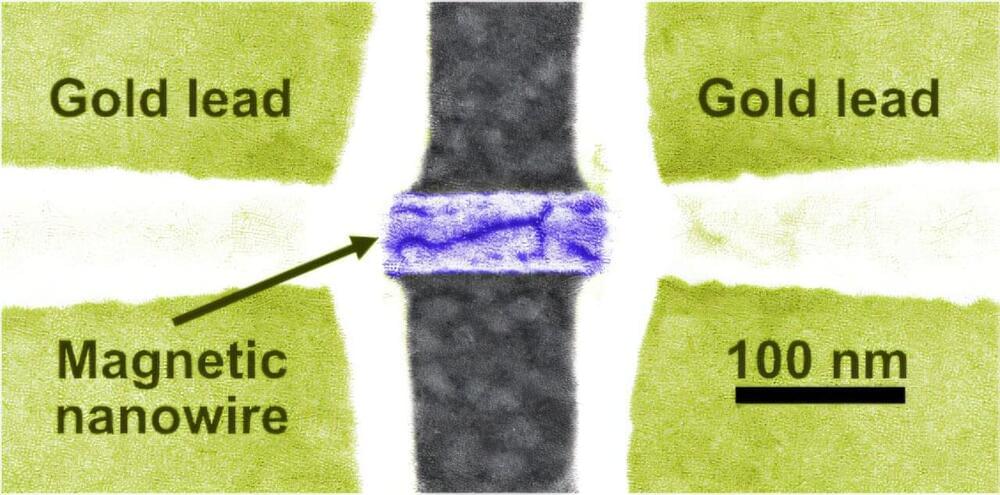

Our data-driven world demands more—more capacity, more efficiency, more computing power. To meet society’s insatiable need for electronic speed, physicists have been pushing the burgeoning field of spintronics.

Traditional electronics use the charge of electrons to encode, store and transmit information. Spintronic devices utilize both the charge and spin-orientation of electrons. By assigning a value to electron spin (up=0 and down=1), spintronic devices offer ultra-fast, energy-efficient platforms.

To develop viable spintronics, physicists must understand the quantum properties within materials. One property, known as spin-torque, is crucial for the electrical manipulation of magnetization that’s required for the next generation of storage and processing technologies.

Observing the effects of special relativity doesn’t necessarily require objects moving at a significant fraction of the speed of light. In fact, length contraction in special relativity explains how electromagnets work. A magnetic field is just an electric field seen from a different frame of reference.

So, when an electron moves in the electric field of another electron, this special relativistic effect results in the moving electron interacting with a magnetic field, and hence with the electron’s spin angular momentum.

The interaction of spin in a magnet field was, after all, how spin was discovered in the 1920 Stern Gerlach experiment. Eight years later, the pair spin-orbit interaction (or spin-orbit coupling) was made explicit by Gregory Breit in 1928 and then found in Dirac’s special relativistic quantum mechanics. This confirmed an equation for energy splitting of atomic energy levels developed by Llewellyn Thomas in 1926, due to 1) the special relativistic magnetic field seen by the electron due to its movement (“orbit”) around the positively charged nucleus, and 2) the electron’s spin magnetic moment interacting with this magnetic field.