Why do plants transport energy so efficiently and quickly?

Quantum field theory suggests that the very structure of the universe could change, altering cosmos as we know it. A new quantum machine might help probe this elusive phenomenon, while also helping improve quantum computers.

Nearly 50 years ago, quantum field theory researchers proposed that the universe exists in a “false vacuum”. This would mean that the stable appearance of the cosmos and its physical laws might be on the verge of collapse. The universe, according to this theory, could be transitioning to a “true vacuum” state.

The theory comes from predictions about the behaviour of the Higgs field associated with the Higgs boson, which Cosmos first looked at nearly a decade ago – the article is worth reading.

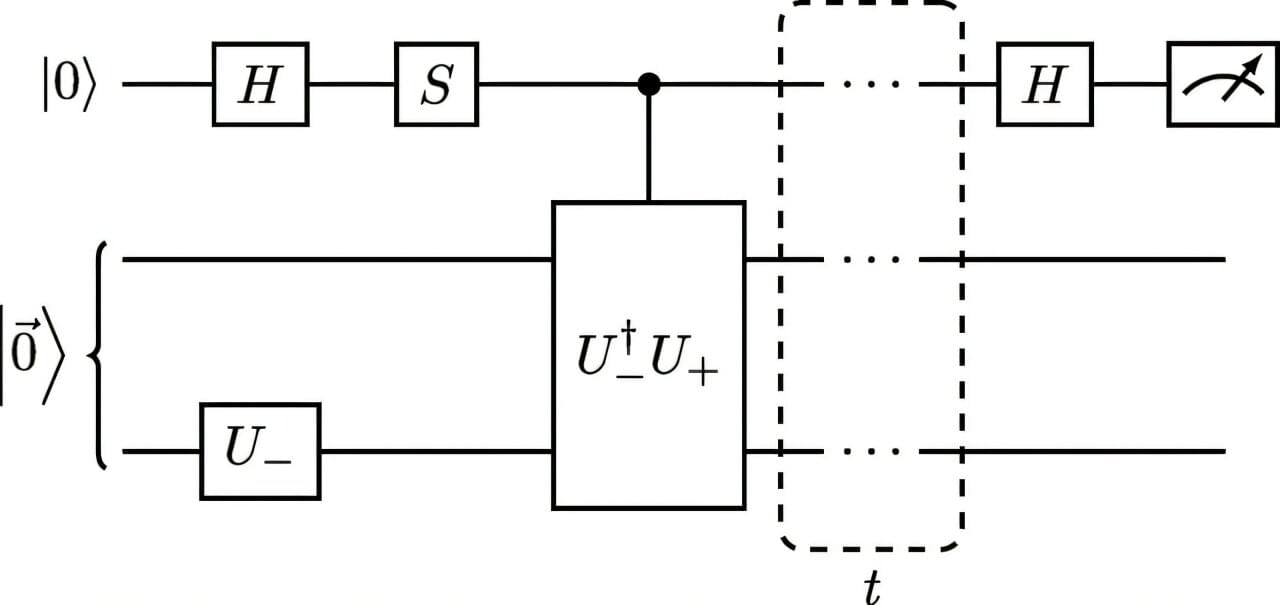

A collaboration between Nordita, the Nordic Institute for Theoretical Physics, hosted by Stockholm University, KTH and Google Quantum AI explores how gravitational fields influence quantum computing hardware, laying the foundation for advances in quantum sensing.

Physicists from Nordita, together with Google Quantum AI, have published a pioneering study that investigates how classical gravitational fields can influence the performance of quantum computing hardware.

The research, led by Professor Alexander Balatsky (Nordita and KTH) and Pedram Roushan (Google’s project leader in quantum computing), highlights a surprising interplay between gravity and quantum systems, breaking new ground in quantum technology. The team also includes Patrick Wong and Joris Schaltegger, researchers at Nordita.

Their work proves that even in isolated quantum systems, disorder naturally grows, aligning quantum mechanics with thermodynamics.

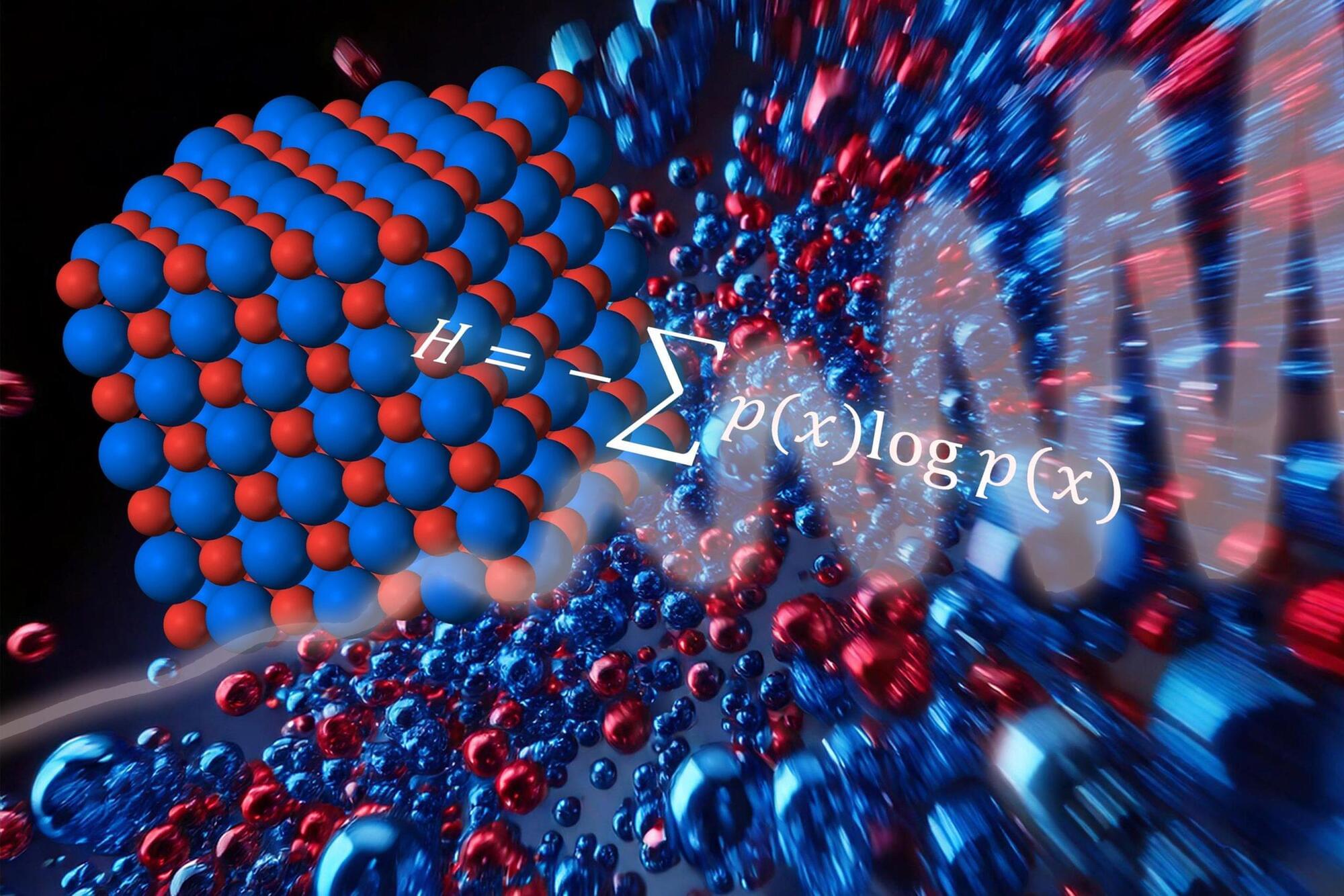

The Paradox of Entropy in Quantum Physics

The second law of thermodynamics is one of the fundamental principles of nature. It states that in a closed system, entropy — the measure of disorder — must always increase over time. This explains why structured systems naturally break down: ice melts into water, and a shattered vase will never reassemble itself. However, quantum physics appears to challenge this rule. Mathematically, entropy in quantum systems seems to remain unchanged, raising a puzzling contradiction.

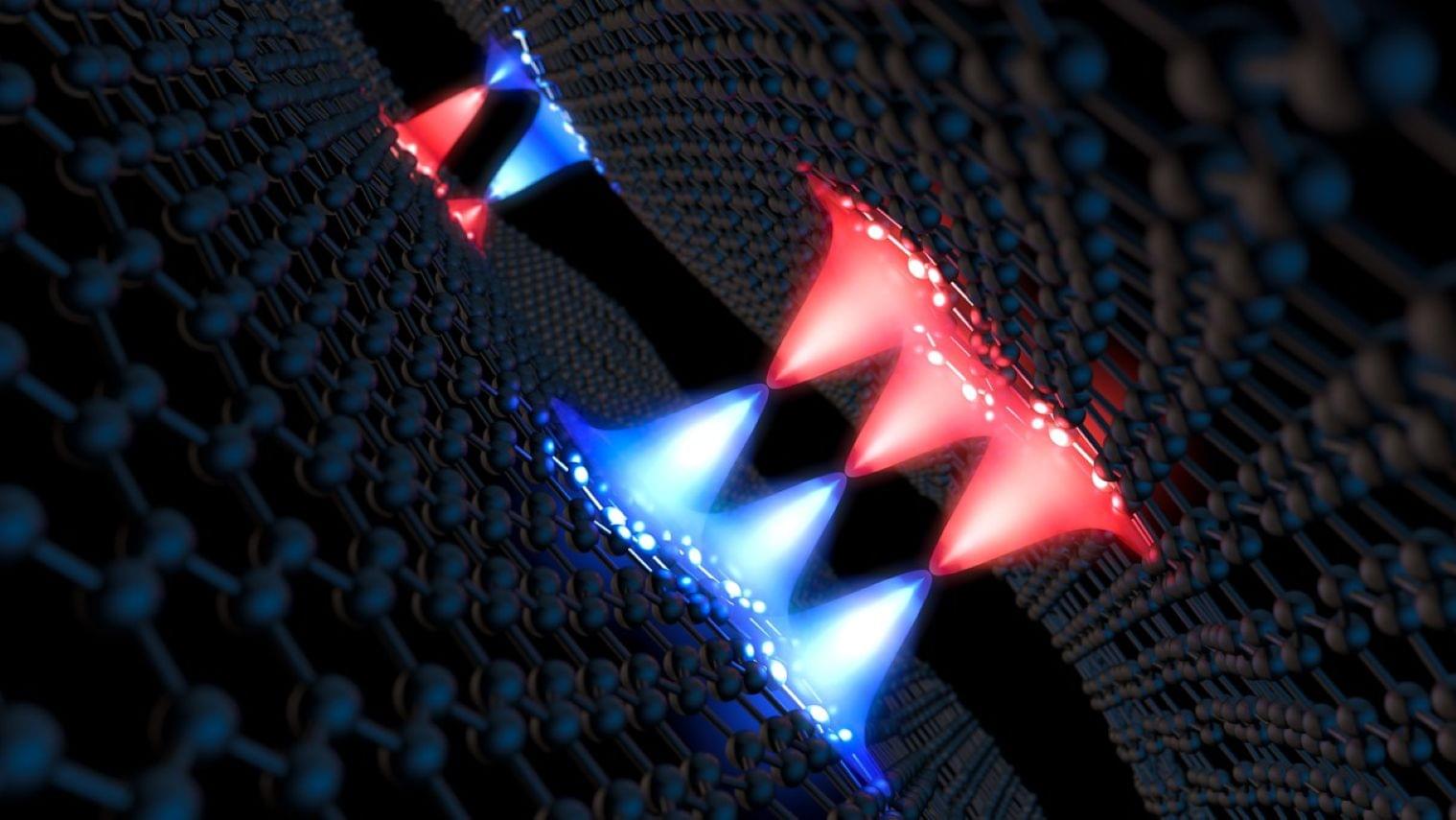

Superconductors can carry electricity without losing energy, a superpower that makes them invaluable for a range of sought-after applications, from maglev trains to quantum computers. Generally, this comes at the price of having to keep them extremely cold, an opportunity cost that has frequently hindered widespread use.

Understanding of how superconductors work has also progressed, but there still remains a great deal about them that is unknown. For example, among many materials known to have superconducting properties, some do not behave according to conventional theory.

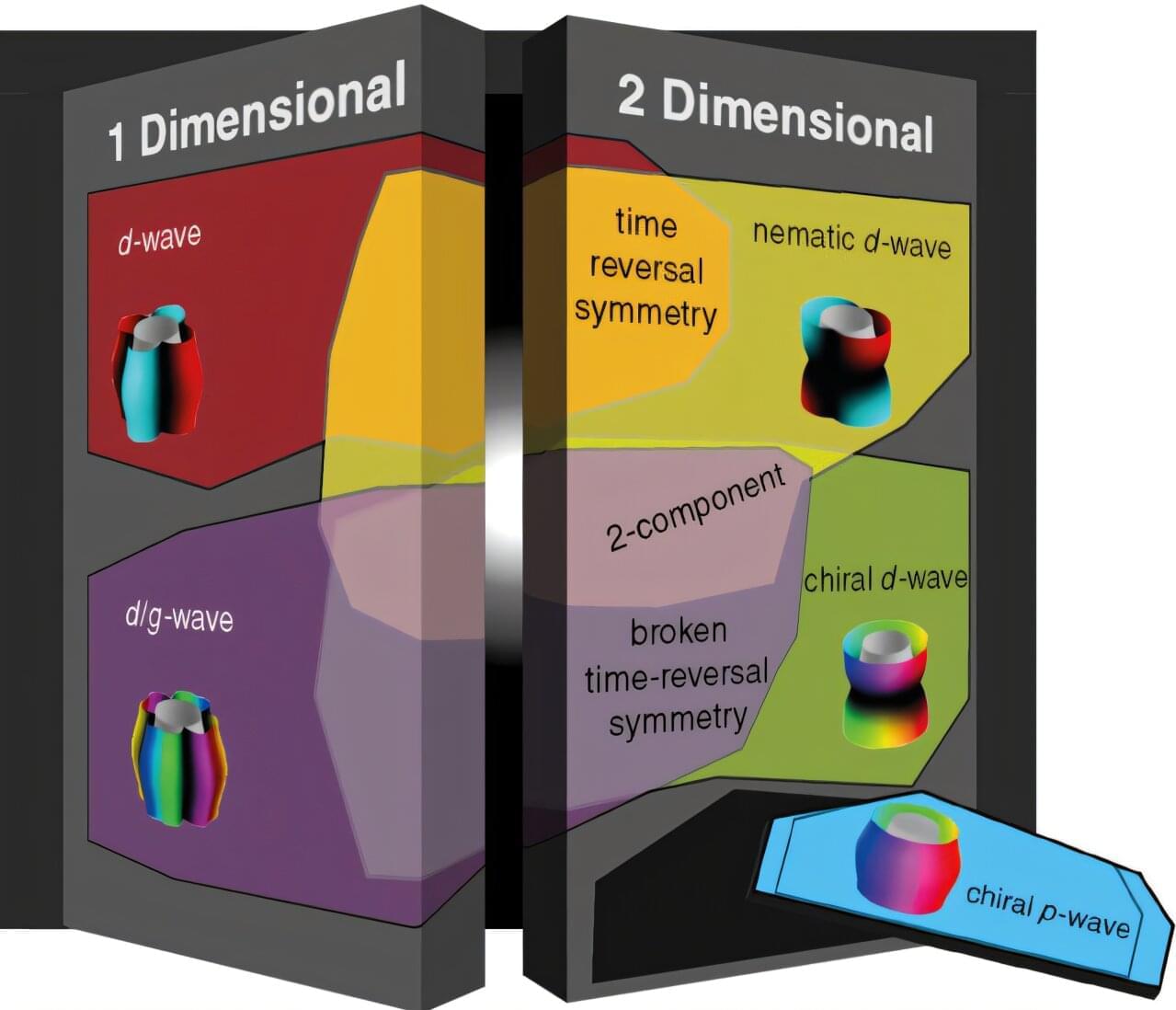

One such puzzling material is strontium ruthenate or Sr2RuO4, which has challenged scientists since it was discovered to be a superconductor in 1994. Initially, researchers thought this material had a special type of superconductivity called a “spin-triplet” state, which is notable for its spin supercurrent. But even after considerable investigation, a full understanding of its behavior has remained a mystery.

In a new study published in Nature Physics, researchers have developed the first controlled method for exciting and observing Kelvin waves in superfluid helium-4.

First described by Lord Kelvin in 1880, Kelvin waves are helical (spiral-shaped) waves that travel along the vortex lines, playing a vital role in how energy dissipates in quantum systems. However, they are difficult to study experimentally.

Creating a controlled setting to observe them has been the biggest challenge that the researchers overcame. Phys.org spoke to the first author of the study, Associate Prof. Yosuke Minowa from Kyoto University.

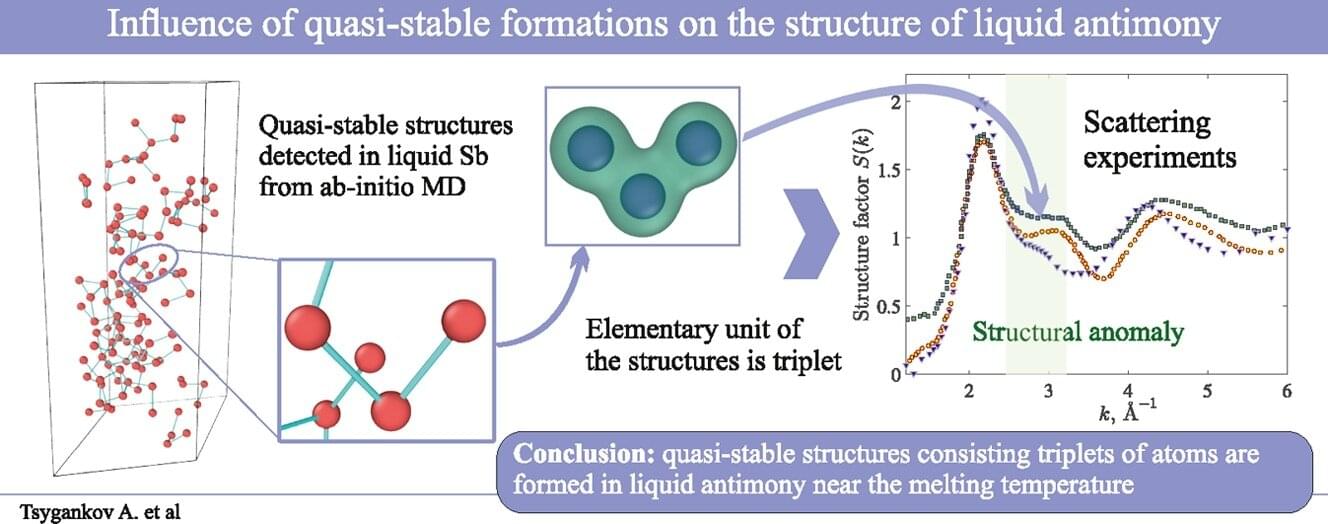

Antimony is widely used in the production of materials for electronics, as well as metal alloys resistant to corrosion and high temperatures.

“Antimony melt is interesting because near the melting point, the atoms in this melt can form bound structures in the form of compact clusters or extended chains and remain in a bound state for quite a long time. We found out that the basic unit of these structures are linked triplets of adjacent atoms, and the centers of mass of these linked atoms are located at the vertices of right triangles. It is from these triplets that larger structures are formed, the presence of which causes anomalous structural features detected in neutron and X-ray diffraction experiments,” explains Dr. Anatolii Mokshin, study supervisor and Chair of the Department of Computational Physics and Modeling of Physical Processes.

The computer modeling method based on quantum-chemical calculations made it possible to reproduce anomalies in the structure of molten antimony with high accuracy.