Tech giant’s researchers say advance could lead to vastly more powerful computers.

Have you ever questioned the true nature of time? Some physicists claim that time is just an illusion, but our lived experience suggests otherwise. In his latest work, Temporal Mechanics: D-Theory as a Critical Upgrade to Our Understanding of the Nature of Time, cyberneticist Alex M. Vikoulov explores how time is deeply rooted in information processing by conscious systems. From species-specific time perception to the implications of Quantum AI’s accelerated mentation, this video presents some mind-bending ideas in the physics of time. Could an advanced superintelligence manipulate its own past states? Could time itself be an editable construct? Could an AI with advanced temporal modeling actually see every possible future simultaneously?

*Preview TEMPORAL MECHANICS eBook/Audiobook on Amazon:

*Preview Audiobook on Audible:

https://www.audible.com/pd/Audiobook/B0CY9HXWXX

#TemporalMechanics #PhysicsofTime #TimeTravel

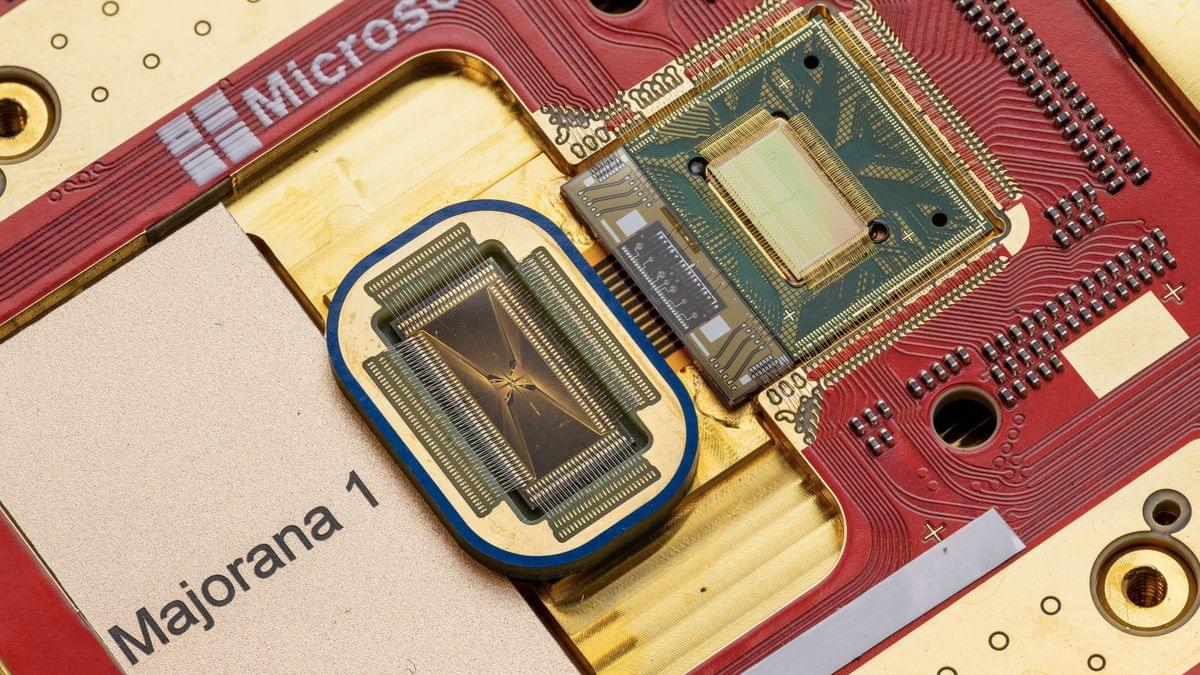

Majorana’s theory proposed that a particle could be its own antiparticle. That means it’s theoretically possible to bring two of these particles together, and they will either annihilate each other in a massive release of energy (as is normal) or can coexist stably when pairing up together — priming them to store quantum information.

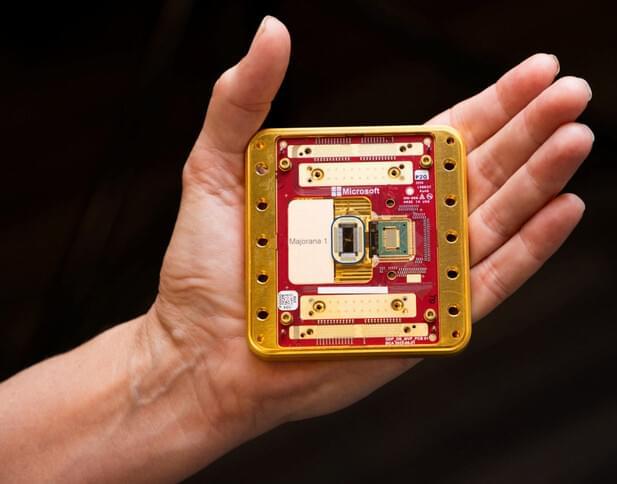

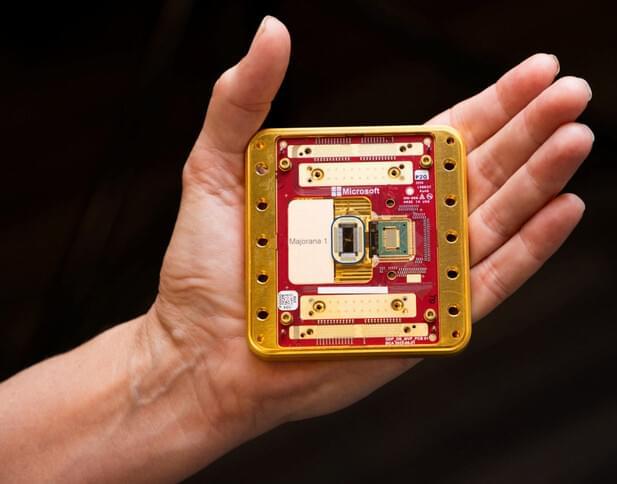

These subatomic particles do not exist in nature, so to nudge them into being, Microsoft scientists had to make a series of breakthroughs in materials science, fabrication methods and measurement techniques. They outlined these discoveries — the culmination of a 17-year-long project — in a new study published Feb. 19 in the journal Nature.

Chief among these discoveries was the creation of this specific topoconductor, which is used as the basis of the qubit. The scientists built their topoconductor from a material stack that combined a semiconductor made of indium arsenide (typically used in devices like night vision goggles) with an aluminum superconductor.

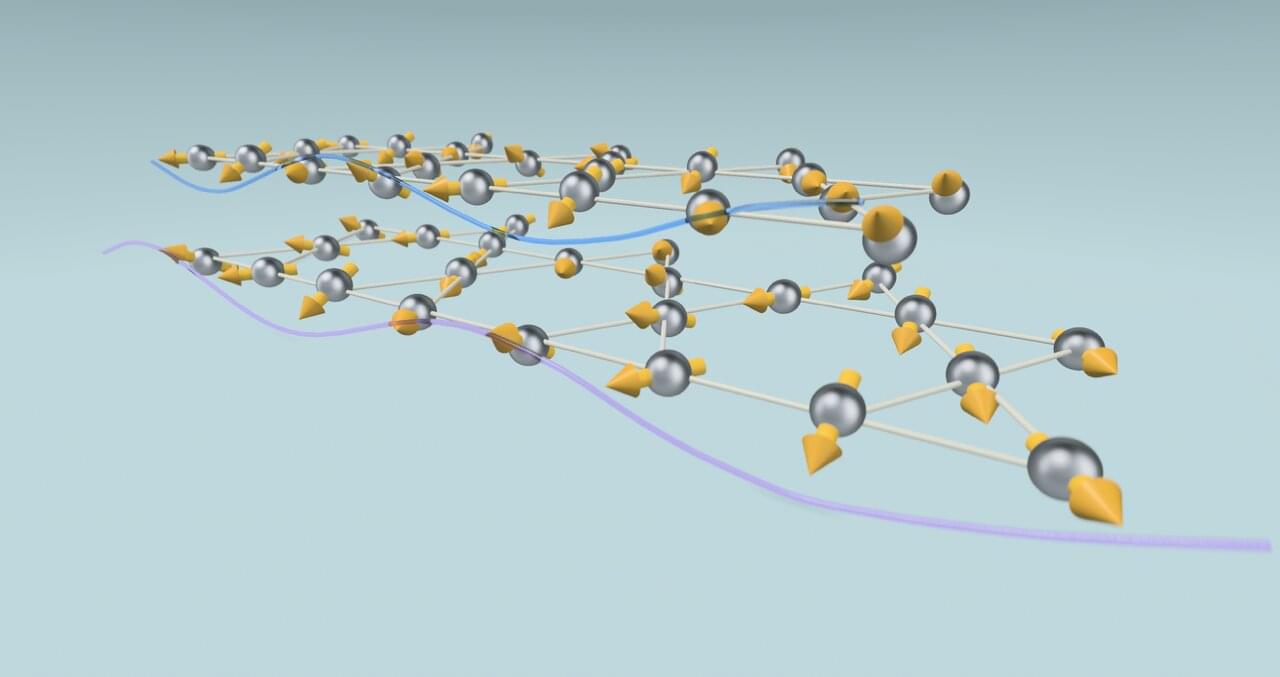

A quantum “miracle material” could support magnetic switching, a team of researchers at the University of Regensburg and University of Michigan has shown.

The study “Controlling Coulomb correlations and fine structure of quasi-one-dimensional excitons by magnetic order” was published in Nature.

This recently discovered capability could help enable applications in quantum computing, sensing and more. While earlier studies identified that quantum entities called excitons are sometimes effectively confined to a single line within the material chromium sulfide bromide, the new research provides a thorough theoretical and experimental demonstration explaining how this is connected to the magnetic order in the material.

In this episode I am looking forward to exploring more about alternate interpretations of Quantum Mechanics. In previous episodes exploring consciousness, I’ve encountered several people who believe that Quantum Mechanics is at the root of consciousness. My current thinking is that it replaces one mystery with another one without really providing an explanation for consciousness. We are still stuck with the options of consciousness being a pre-existing property of the universe or some aspect of it, vs. it being an emergent feature of a processing network. Either way, quantum mechanics is an often misunderstood brilliant theory at the root of physics. It tells us that basic particles don’t exist at a specific position and momentum—they are, however, represented very accurately as a smooth wavefunction that can be used to calculate the distribution of a set of measurements on identical particles. The process of observation seems to cause the wavefunction to randomly collapse to a localized spot. Nobody knows for certain what causes this collapse. This is known as the measurement problem. The many worlds theorem says the wavefunction doesn’t collapse. It claims that the wavefunction describes all the possible universes that exist and the process of measurement just tells us which universe we are living in.

My guest is a leading proponent of transactional quantum mechanics.

Dr. Ruth E. Kastner earned her M.S. in Physics and Ph.D. in History and Philosophy of Science from the University of Maryland. Since that time, she has taught widely and conducted research in Foundations of Physics, particularly in interpretations of quantum theory. She was one of three winners of the 2021 Alumni Research Award at the University of Maryland, College Park (https://tinyurl.com/2t56yrp2). She is the author of 3 books: The Transactional Interpretation of Quantum Theory: The Reality of Possibility (Cambridge University Press, 2012; 2nd edition just published, 2022), Understanding Our Unseen Reality: Solving Quantum Riddles (Imperial College Press, 2015); and Adventures In Quantumland: Exploring Our Unseen Reality (World Scientific, 2019). She has presented talks and interviews throughout the world and in video recordings on the interpretational challenges of quantum theory, and has a blog at transactionalinterpretation.org. She is also a dedicated yoga practitioner and received her 200-Hour Yoga Alliance Instructor Certification in February, 2020.

Visit my website at www.therationalview.ca.

Join the Facebook conversation @TheRationalView.

Twitter @AlScottRational.

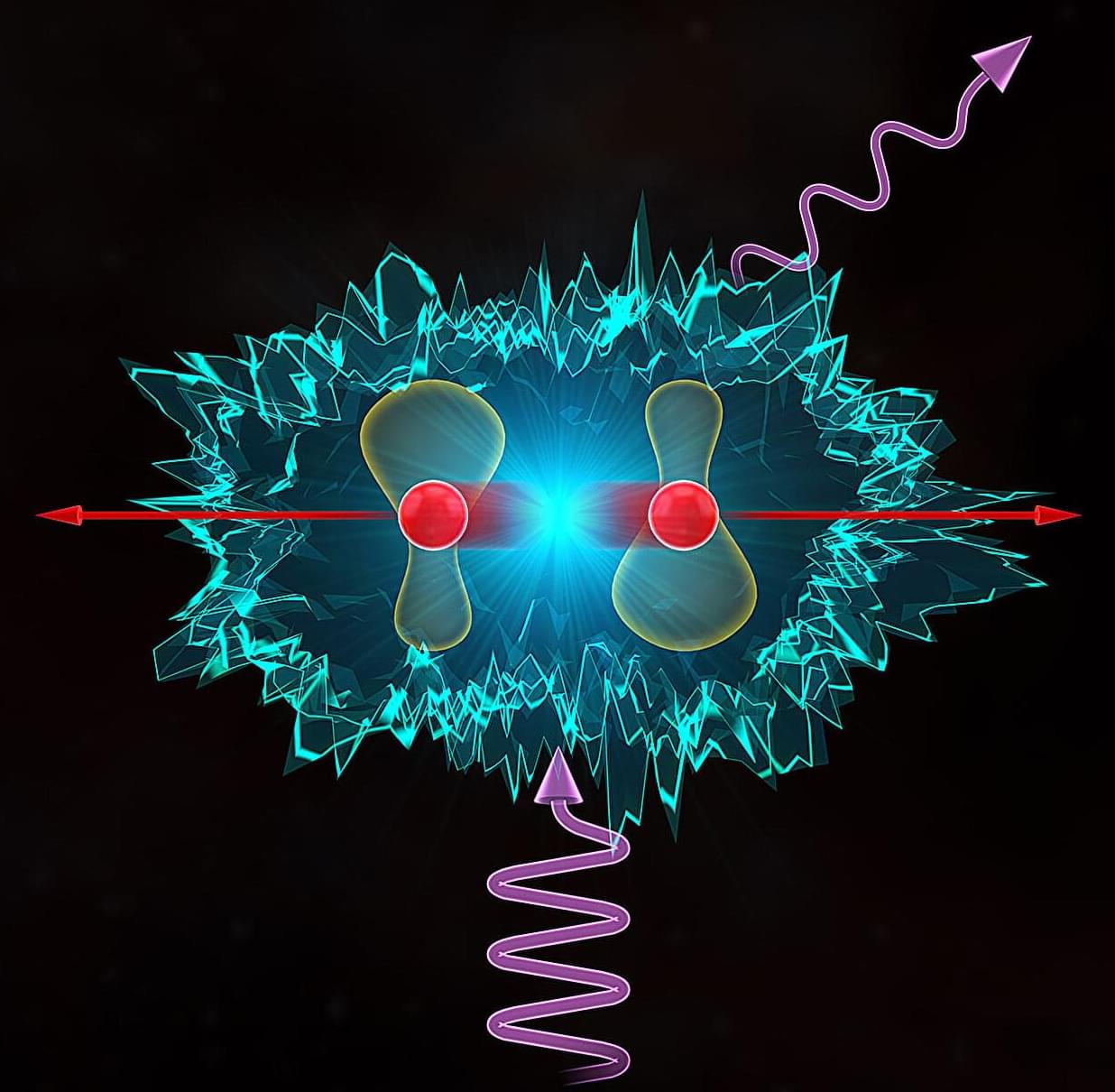

When atoms collide, their exact structure—for example, the number of electrons they have or even the quantum spin of their nuclei—has a lot to say about how they bounce off each other. This is especially true for atoms cooled to near-zero Kelvin, where quantum mechanical effects give rise to unexpected phenomena. Collisions of these cold atoms can sometimes be caused by incoming laser light, resulting in the colliding atom-pair forming a short-lived molecular state before disassociating and releasing an enormous amount of energy.

These so-called light-assisted collisions, which can happen very quickly, impact a broad range of quantum science applications, yet many details of the underlying mechanisms are not well understood.

In a new study published in Physical Review Letters, JILA Fellow and University of Colorado Boulder physics professor Cindy Regal, along with former JILA Associate Fellow Jose D’Incao (currently an assistant professor of physics at the University of Massachusetts, Boston) and their teams developed new experimental and theoretical techniques for studying the rates at which light-assisted collisions occur in the presence of small atomic energy splittings.

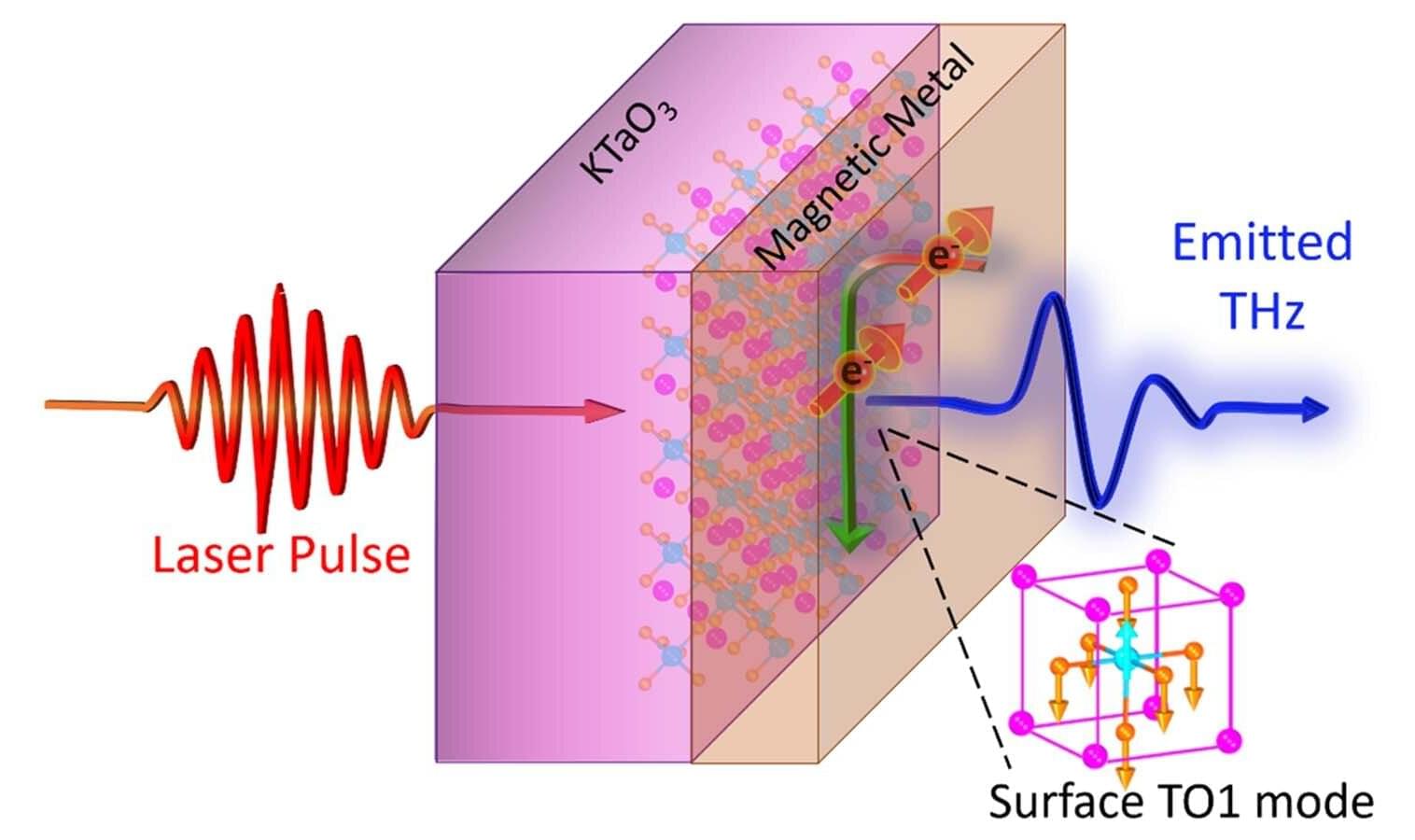

Scientists are racing to develop new materials for quantum technologies in computing and sensing for ultraprecise measurements. For these future technologies to transition from the laboratory to real-world applications, a much deeper understanding is needed of the behavior near surfaces, especially those at interfaces between materials.

Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory have unveiled a new technique that could help advance the development of quantum technology. Their innovation, surface-sensitive spintronic terahertz spectroscopy (SSTS), provides an unprecedented look at how quantum materials behave at interfaces.

The work is published in the journal Science Advances.

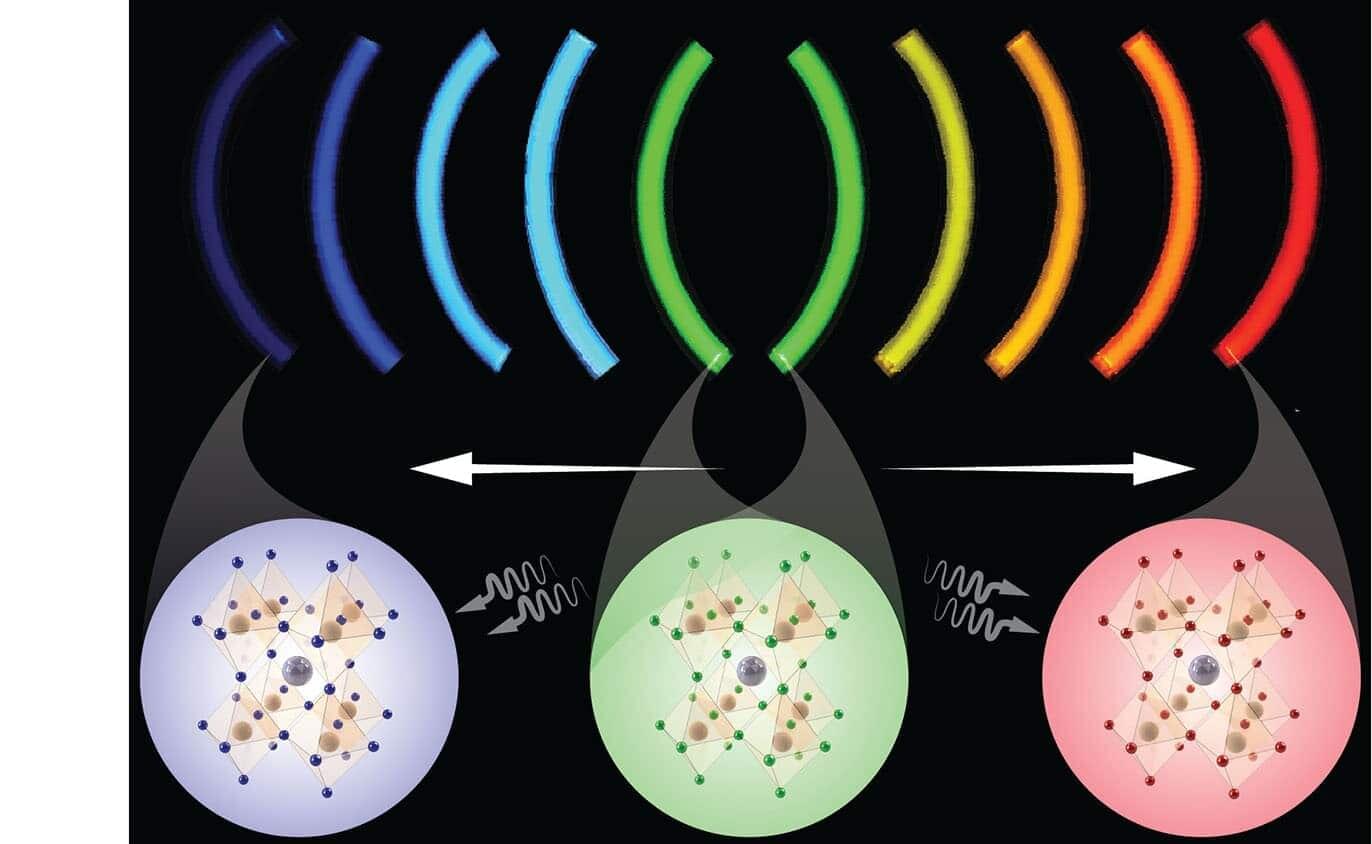

Researchers at North Carolina State University have demonstrated a new technique that uses light to tune the optical properties of quantum dots—making the process faster, more energy-efficient and environmentally sustainable—without compromising material quality.

The findings are published in the journal Advanced Materials.

“The discovery of quantum dots earned the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 2023 because they are used in so many applications,” says Milad Abolhasani, corresponding author of a paper on the work and ALCOA Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering at NC State. “We use them in LEDs, solar cells, displays, quantum technologies and so on. To tune their optical properties, you need to tune the bandgap of quantum dots—the minimum energy required to excite an electron from a bound state to a free-moving state—since this directly determines the color of light they emit.

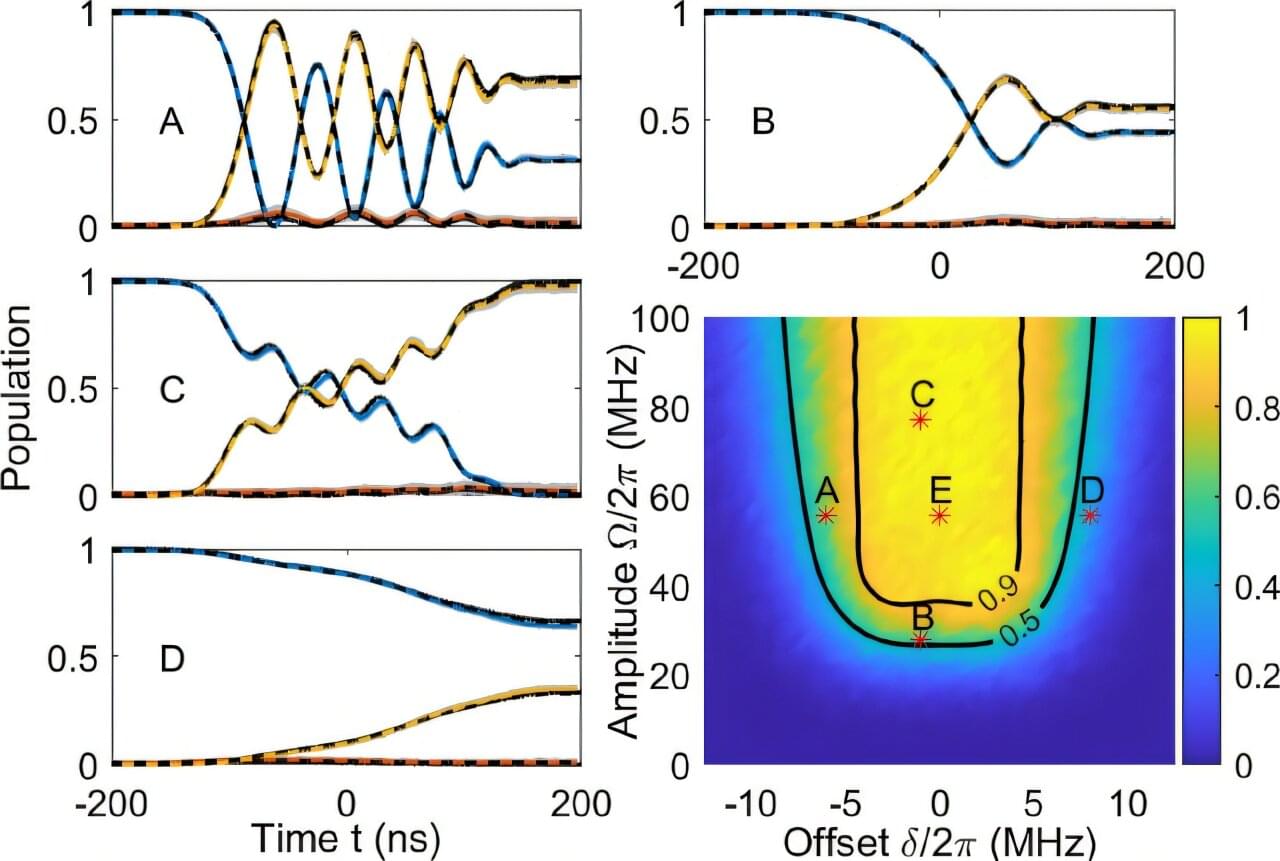

Physicists have found a simple and effective way to skip over an energy level in a three-state system, potentially leading to increased quantum computational power with fewer qubits.

Nearly a century ago, Lev Landau, Clarence Zener, Ernst Stückelberg, and Ettore Majorana found a mathematical formula for the probability of jumps between two states in a system whose energy is time-dependent. Their formula has since had countless applications in various systems across physics and chemistry.

Now physicists at Aalto University’s Department of Applied Physics have shown that the jump between different states can be realized in systems with more than two energy levels via a virtual transition to an intermediate state and by a linear chirp of the drive frequency. This process can be applied to systems where it is not possible to modify the energy of the levels.

When it comes to layered quantum materials, current understanding only scratches the surface; so demonstrates a new study from the Paul Scherrer Institute PSI. Using advanced X-ray spectroscopy at the Swiss Light Source SLS, researchers uncovered magnetic phenomena driven by unexpected interactions between the layers of a kagome ferromagnet made from iron and tin. This discovery challenges assumptions about layered alloys of common metals, providing a starting point for developing new magnetoelectric devices and rare-earth-free motors.

The research is published in the journal Nature Communications.

Patterns are everything. With quantum materials, it’s not just what they’re made of but how their atoms or molecules are organized that gives rise to the exotic properties that excite researchers with their promise for future technologies.