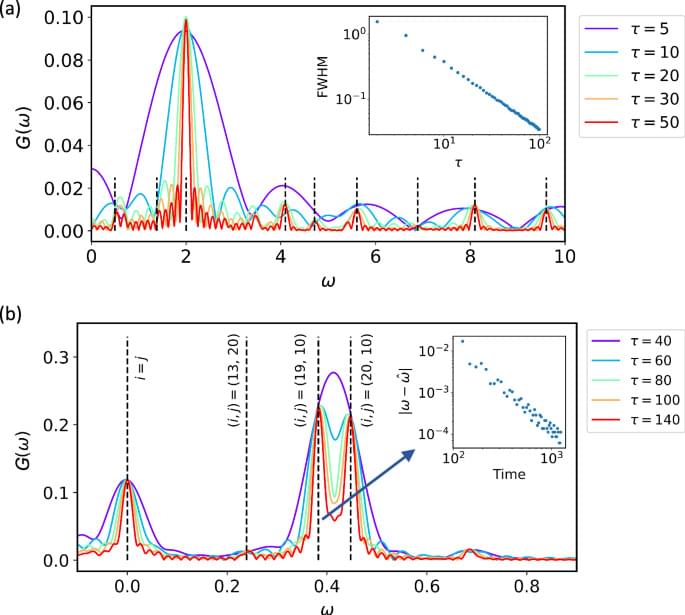

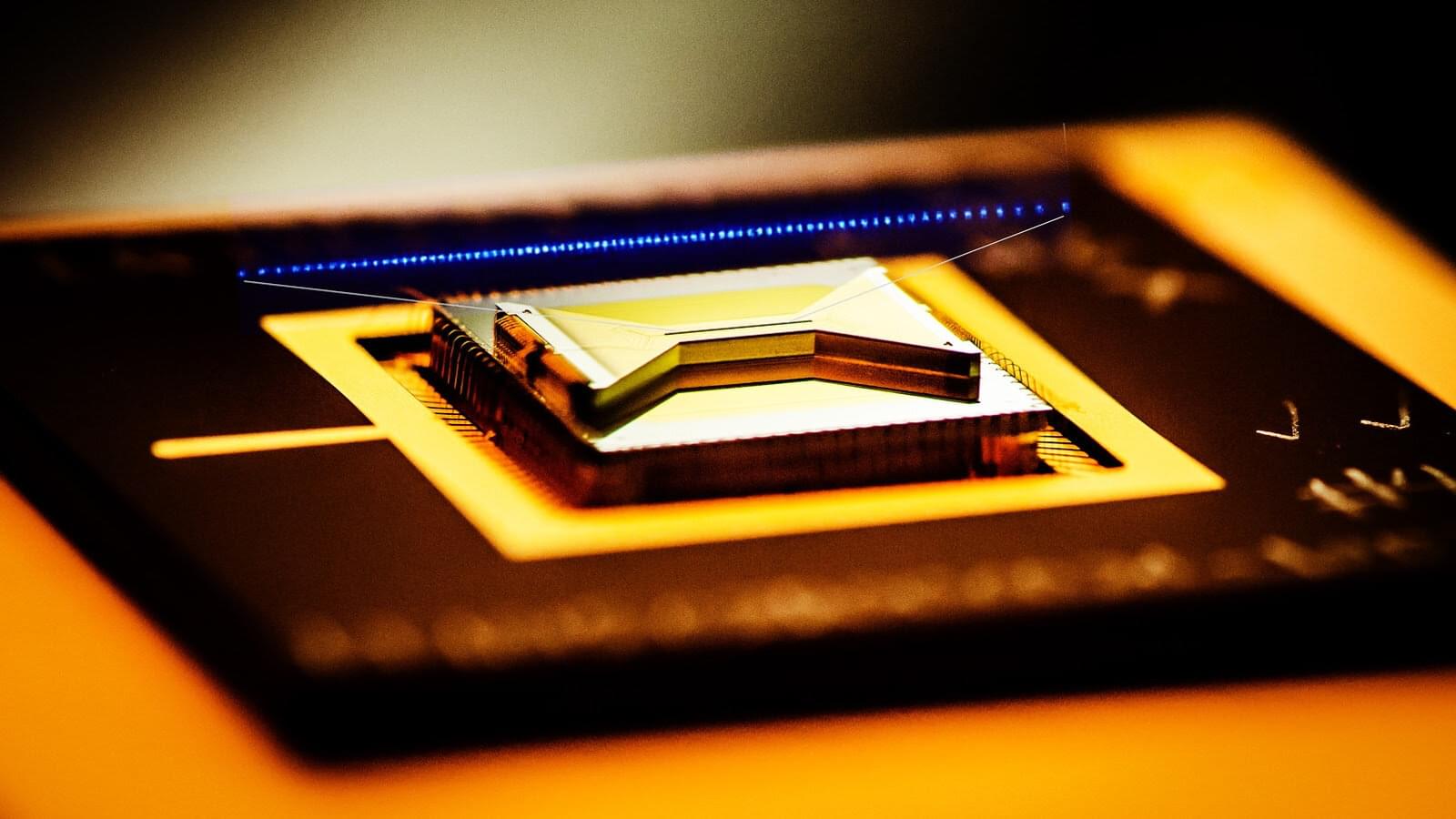

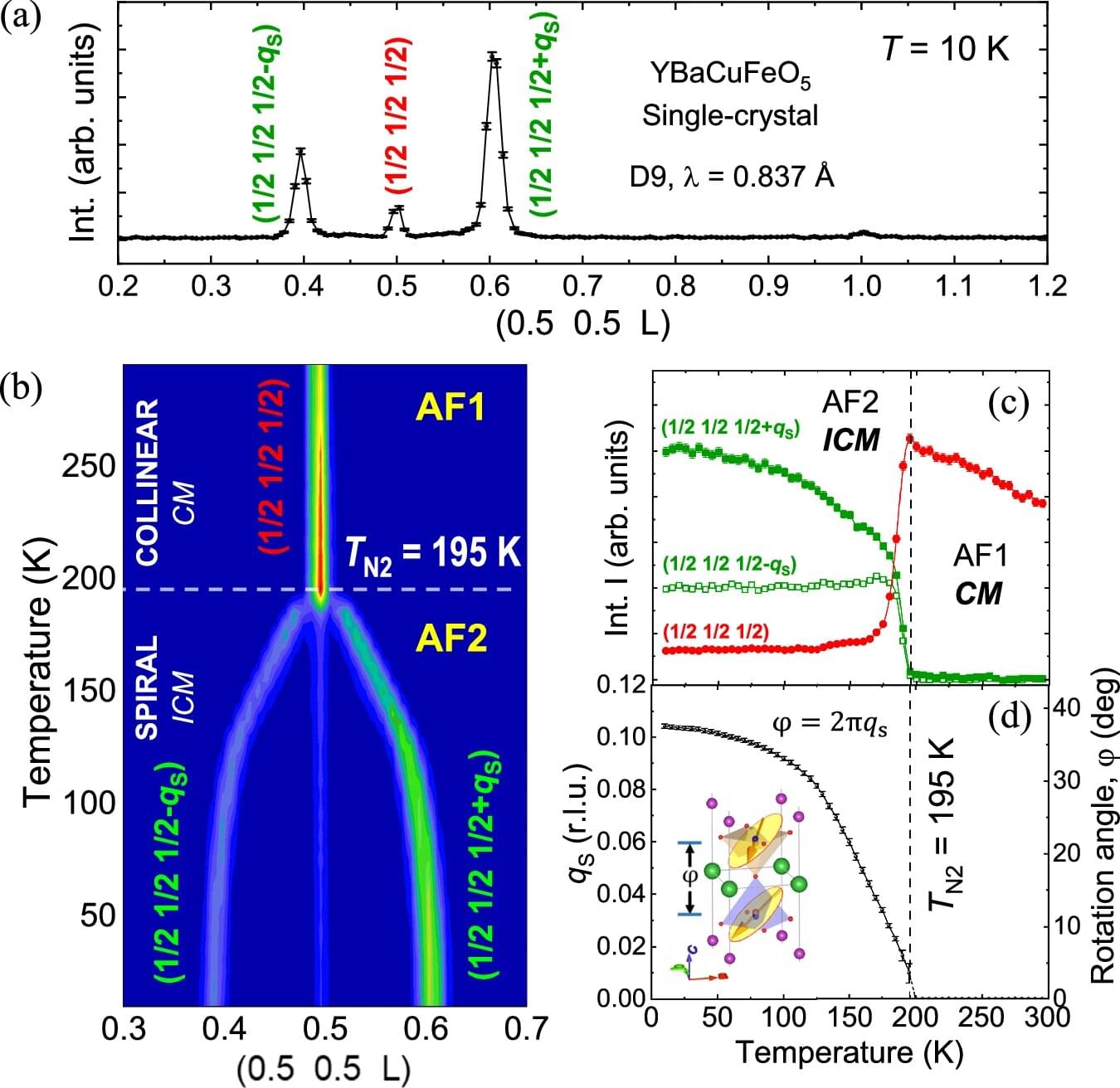

Estimating spectral features of quantum many-body systems has attracted great attention in condensed matter physics and quantum chemistry. To achieve this task, various experimental and theoretical techniques have been developed, such as spectroscopy techniques1,2,3,4,5,6,7 and quantum simulation either by engineering controlled quantum devices8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16 or executing quantum algorithms17,18,19,20 such as quantum phase estimation and variational algorithms. However, probing the behaviour of complex quantum many-body systems remains a challenge, which demands substantial resources for both approaches. For instance, a real probe by neutron spectroscopy requires access to large-scale facilities with high-intensity neutron beams, while quantum computation of eigenenergies typically requires controlled operations with a long coherence time17,18. Efficient estimation of spectral properties has become a topic of increasing interest in this noisy intermediate-scale quantum era21.

A potential solution to efficient spectral property estimation is to extract the spectral information from the dynamics of observables, rather than relying on real probes such as scattering spectroscopy, or direct computation of eigenenergies. This approach capitalises on the basics in quantum mechanics that spectral information is naturally carried by the observable’s dynamics10,20,22,23,24,25,26. In a solid system with translation invariance, for instance, the dynamic structure factor, which can be probed in spectroscopy experiments7,26, reaches its local maximum when both the energy and momentum selection rules are satisfied. Therefore, the energy dispersion can be inferred by tracking the peak of intensities in the energy excitation spectrum.