The experiment provided further proof of the reality of photons, yet Millikan didn’t accept their existence until later in his career.

MIT researchers are developing techniques to make quantum gates, the basic operations of a quantum computer, as fast as possible in order to reduce the impact of decoherence. However, as gates get faster, another type of error, arising from counter-rotating dynamics, can be introduced because of the way qubits are controlled using electromagnetic waves.

Single-qubit gates are usually implemented with a resonant pulse, which induces Rabi oscillations between the qubit states. When the pulses are too fast, however, “Rabi gates” are not so consistent, due to unwanted errors from counter-rotating effects. The faster the gate, the more the counter-rotating error is manifest. For low-frequency qubits such as fluxonium, counter-rotating errors limit the fidelity of fast gates.

“Getting rid of these errors was a fun challenge for us,” says Rower. “Initially, Leon had the idea to utilize circularly polarized microwave drives, analogous to circularly polarized light, but realized by controlling the relative phase of charge and flux drives of a superconducting qubit. Such a circularly polarized drive would ideally be immune to counter-rotating errors.”

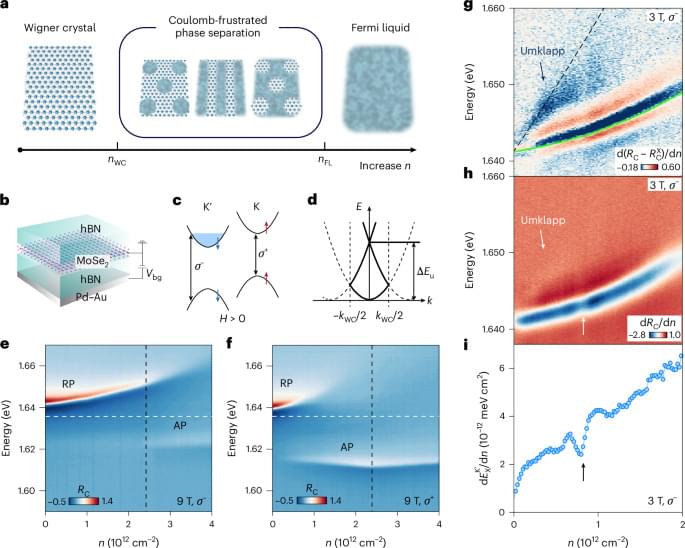

Competition between different possible ground states of strongly correlated electron systems can lead to the emergence of mixed states called microemulsions. Now this phenomenon is reported at the meltingion of a Wigner crystal.

In the world of tiny particles and quantum physics, scientists often study how electrons—the fundamental particles that carry electricity—behave under different conditions. When electrons interact strongly with each other, they can form various states of matter, much like how water can turn into ice or steam. Sometimes, these states compete, leading to complex and fascinating patterns. One such pattern is called a microemulsion phase, where tiny regions of different electron states mix together, creating a kind of quantum “patchwork quilt.”

In this study, researchers explored a special material called a MoSe₂ monolayer, which is an ultra-thin layer of atoms that can host electrons. By cooling this material to extremely low temperatures and using advanced light-based techniques, they observed something remarkable: aion between two electron states—a rigid Wigner crystal (where electrons are locked in place) and a flowing electron liquid. During thision, the electrons formed a microemulsion phase, blending crystal-like and liquid-like regions in a unique, self-organized pattern.

The team detected this phase by looking for specific clues, such as changes in how light reflects off the material, how the electrons respond to magnetic fields, and how they scatter off each other. These clues confirmed that the microemulsion is a distinct and exotic state of electronic matter, offering new insights into how electrons can organize themselves in surprising ways. This discovery not only deepens our understanding of quantum materials but also opens the door to exploring new phases of matter that could one day power advanced technologies.

Quantum foam itself released gravitational waves that eventually shaped the cosmic universe.

Over billions of years, these stretched ripples grew into clumps of matter, forming the first stars and galaxies. Eventually, they created a massive network of galaxies and dark matter called the cosmic web, which spans the entire universe today.

A new study suggests that the cosmic web could have formed without relying on inflation driven by a scalar field. Instead, it proposes a novel mechanism that suggests that inflation arises from gravitational wave amplification.

Inflation is believed to have laid the foundation of everything there is out in space. However, nobody knows when it happened, why it happened, or what caused it. Plus, scientists don’t have any solid evidence to confirm whether it happened.

Catch a glimpse of the near future as AI and Quantum Computing transform how we live. Eric Schmidt, decade-long CEO of Google, joins Brian Greene to explore the horizons of innovation, where digital and quantum frontiers collide to spark a new era of discovery.

This program is part of the Big Ideas series, supported by the John Templeton Foundation.

Participants:

Eric Schmidt.

Moderator:

Brian Greene.

WSF Landing Page: https://www.worldsciencefestival.com/.…

SUBSCRIBE to our youtube channel and \.

How Symmetry Shapes the Universe: A Peek into Persistent Symmetry Breaking.

Imagine a world where certain symmetries—like the balance between left and right or up and down—are spontaneously disrupted, but this disruption persists regardless of temperature. Scientists are exploring this fascinating behavior in a special type of mathematical framework known as biconical vector models. These models examine how symmetries behave under specific conditions, especially in a universe with two spatial dimensions and one time dimension (2+1 dimensions).

This study takes a closer look at these models and reveals exciting new insights about symmetry breaking in a way that respects established physical principles. Here’s what the researchers discovered:

1. Symmetry Breaking Basics: The study confirms that symmetry can break persistently when these models are designed to include both continuous and discrete symmetry features (described by the mathematical groups O(N)×Z₂). This breaking shifts from one type of symmetry (O(N)×Z₂) to another (O(N)) as temperature rises, but only under certain conditions.

2. Precision at Zero Temperature: By using advanced computational methods, the team accurately described how these models behave when the temperature is absolute zero. Their findings are valid for a wide range of systems, provided the number of components, N, is 2 or greater.

3. Finite-Temperature Effects: As the temperature increases, the discrete symmetry (Z₂) remains the only one to break, ensuring that the laws of physics, specifically the Hohenberg-Mermin-Wagner theorem, are respected. This theorem essentially states that continuous symmetries cannot break spontaneously in 2D systems at finite temperatures.

4. A Critical Threshold: The researchers calculated that this unusual symmetry-breaking phenomenon can only be observed when N (the number of components in the system) exceeds a critical value, approximately 15.

In the fascinating intersection of quantum computing and the human experience of time, lies a groundbreaking theory that challenges our conventional narratives: the D-Theory of Time. This theory proposes a revolutionary perspective on time not as fundamental but as an emergent phenomenon arising from the quantum mechanical fabric of the universe.

#TemporalMechanics #DTheory #QuantumComputing #QuantumAI

“In a sense, Nature has been continually computing the ‘next state’ of the Universe for billions of years; all we have to do — and actually all we can do — is ‘hitch a ride’ on this huge ongoing [quantum] computation.” — Tommaso Toffoli

In my new book Temporal Mechanics: D-Theory as a Critical Upgrade to Our Understanding of the Nature of Time (2025), I defend the D-Theory of Time, predicated or reversible quantum computing at large, which represents a novel framework that challenges our conventional understanding of time and computing. Here, we explore the foundational principles of D-Theory, its implications for reversible quantum computing, and how it could potentially revolutionize our approach to computing, information processing, and our understanding of the universe.