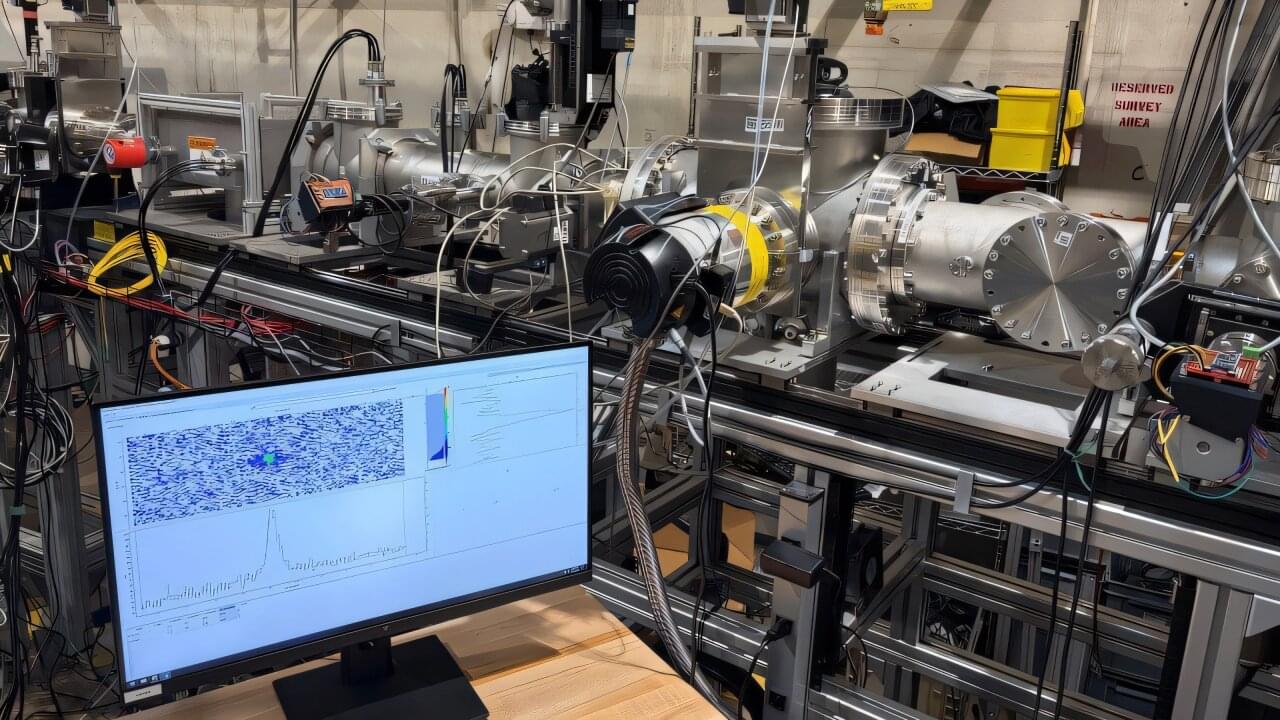

Plasma mirrors capable of withstanding the intensity of powerful lasers are being designed through an emerging machine learning framework. Researchers in Physics and Computer Science at the University of Strathclyde have pooled their knowledge of lasers and artificial intelligence to produce a technology that can dramatically reduce the time it takes to design advanced optical components for lasers—and could pave the way for new discoveries in science.

High-power lasers can be used to develop tools for health care, manufacturing and nuclear fusion. However, these are becoming large and expensive due to the size of their optical components, which is currently necessary to keep the laser beam intensity low enough not to damage them. As the peak power of lasers increases, the diameters of mirrors and other optical components will need to rise from approximately one meter to more than 10 meters. These would weigh several tons, making them difficult and expensive to manufacture.