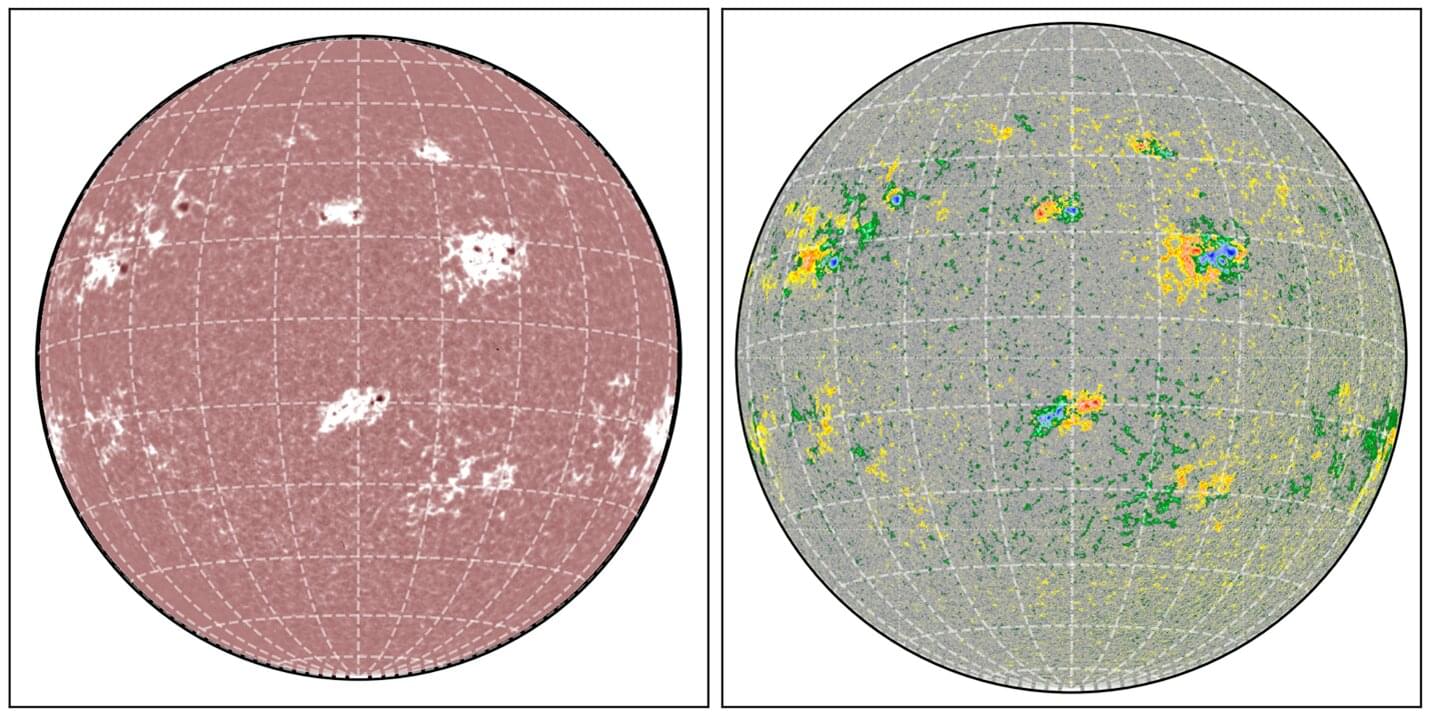

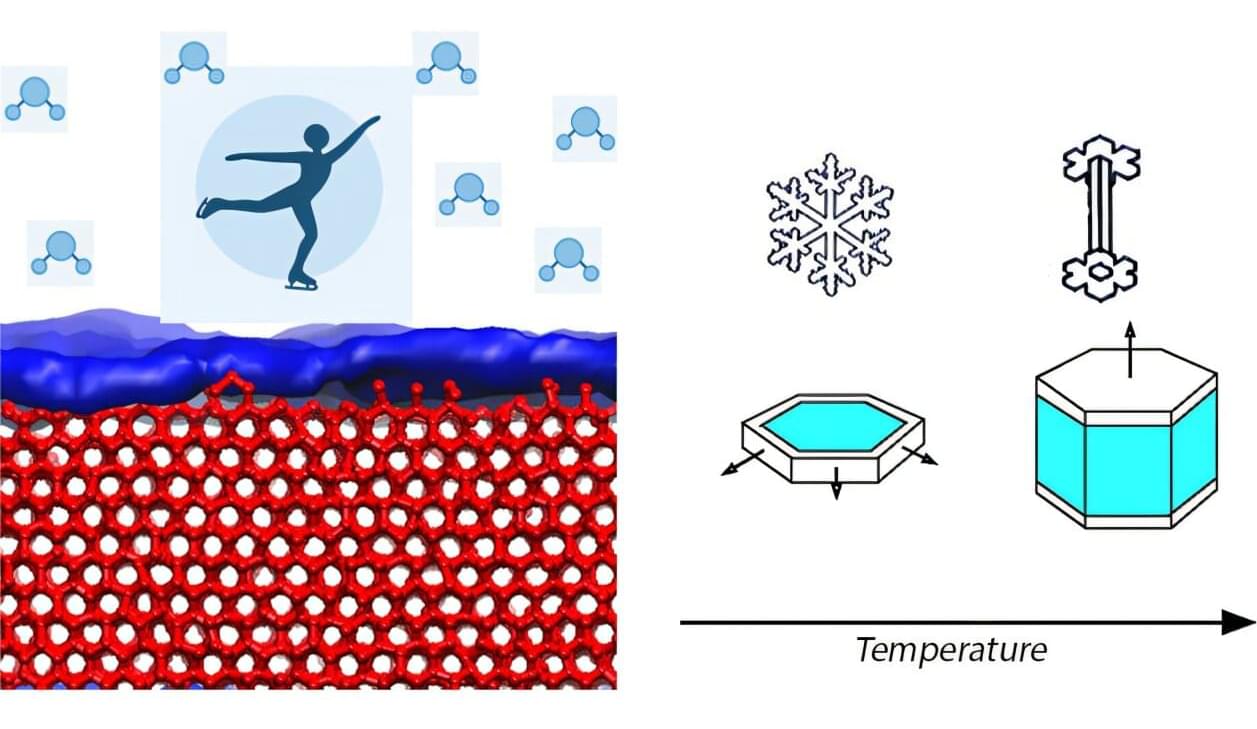

Scientists have used a NASA-grade supercomputer to push our planet to its limits, virtually fast‑forwarding the clock until complex organisms can no longer survive. The result is a hard upper bound on how long Earth can sustain breathable air and liquid oceans, and it is far less about sudden catastrophe than a slow suffocation driven by the Sun itself. The work turns a hazy, far‑future question into a specific timeline for the end of life as we know it.

Instead of fireballs or rogue asteroids, the simulations point to a world that quietly runs out of oxygen, with only hardy microbes clinging on before even they disappear. It is a stark reminder that Earth’s habitability is not permanent, yet it also stretches over such vast spans of time that our immediate crises still depend on choices made this century, not on the Sun’s distant evolution.

The new modeling effort starts from a simple premise: if I know how the Sun brightens over time and how Earth’s atmosphere responds, I can calculate when conditions for complex life finally fail. Researchers fed a high‑performance system with detailed physics of the atmosphere, oceans and carbon cycle, then let it run through hundreds of thousands of scenarios until the planet’s chemistry tipped past a critical point. One study describes a supercomputer simulation that projects life on Earth ending in roughly 1 billion years, once rising solar heat strips away most atmospheric oxygen.