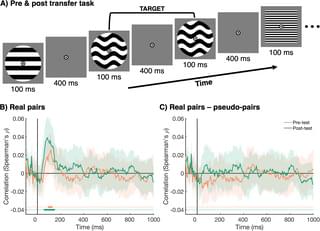

Whether great minds think alike is up for debate, but the collaborating minds of two people working on a shared task process information alike, according to a study published in PLOS Biology by Denise Moerel and colleagues from Western Sydney University in Australia.

Humans rely on collaboration for everything from raising food to raising children. But to cooperate successfully, people need to make sure that they are seeing the same things and working within the same rules. We must agree that the red fruits are the ones that are ripe and that we will leave green fruits alone.

Behavioral collaboration requires that people think in the same way and follow the same instructions. To better understand people’s cognitive processes during a shared task, the authors of this study collected data from 24 pairs of people.