Despite decades of research, the mechanisms behind fast flashes of insight that change how a person perceives their world, termed “one-shot learning,” have remained unknown. A mysterious type of one-shot learning is perceptual learning, in which seeing something once dramatically alters our ability to recognize it again.

Now a new study, the researchers address the moments when we first recognize a blurry object, a primal ability that enabled our ancestors to avoid threats.

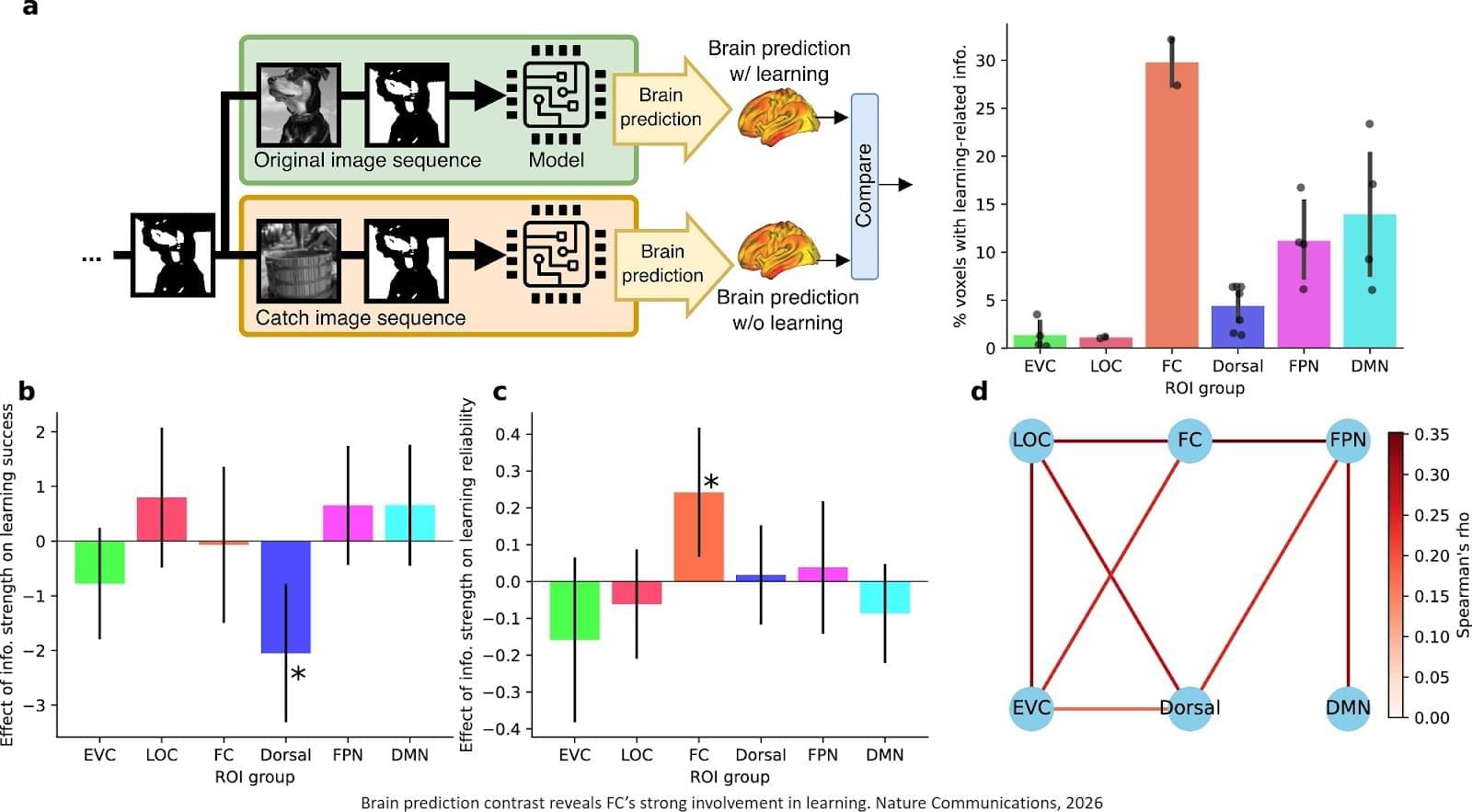

Published in Nature Communications, the new work pinpoints for the first time the brain region called the high-level visual cortex (HLVC) as the place where “priors” — images seen in the past and stored — are accessed to enable one-shot perceptual learning.

“Our work revealed, not just where priors are stored, but also the brain computations involved,” said co-senior study author.

Importantly, past studies had shown that patients with schizophrenia and Parkinson’s disease have abnormal one-shot learning, such that previously stored priors overwhelm what a person is presently looking at to generate hallucinations.

“This study yielded a directly testable theory on how priors act up during hallucinations, and we are now investigating the related brain mechanisms in patients with neurological disorders to reveal what goes wrong,” added the author.

The research team is also looking into likely connections between the brain mechanisms behind visual perception and the better-known type of “aha moment” when we comprehend a new idea. ScienceMission sciencenewshighlights.