New in JNeurosci from Wei, Tao, Bi et al: Smokers who have quit their nicotine use have altered brain activity linked to heightened pain sensitivity and a need for more postoperative pain relief.

▶️

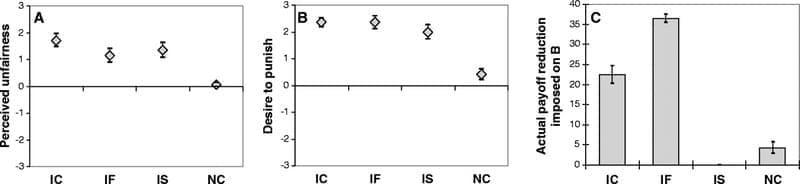

Perioperative abstinent smokers experience heightened pain sensitivity and increased postoperative analgesic requirements, likely due to nicotine withdrawal-induced hyperalgesia. However, the underlying neural mechanisms in humans remain unclear. To address this issue, this study enrolled 60 male patients (30 abstinent smokers and 30 nonsmokers) undergoing partial hepatectomy, collecting clinical data, smoking history, pain-related measures, and resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI). Compared to nonsmokers, abstinent smokers showed lower pain threshold and higher postoperative analgesic requirements. Neuroimaging revealed altered brain function in abstinent smokers, including reduced fractional amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations (fALFF, 0.01 – 0.1 Hz) in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), increased regional homogeneity (ReHo) in the left middle occipital gyrus, and decreased functional connectivity (FC) between the vmPFC to both the bilateral middle temporal gyrus and precuneus. Preoperative pain threshold was positively correlated with abstinence duration and specific regional brain activities and connectivity. Further, the observed association between abstinent time and pain threshold was mediated by the calcarine and posterior cingulate cortex activity. The dysfunction in vmPFC and left anterior cingulate cortex was totally mediated by the association between withdrawal symptoms and postoperative analgesic requirements. These findings suggest that nicotine withdrawal might alter brain functional activity and contribute to hyperalgesia for the abstinent smokers. This study provided novel insights into the supraspinal neurobiological mechanisms underlying nicotine withdrawal-induced hyperalgesia and potential therapeutic targets for postoperative pain in abstinent smokers.

Significance statement Abstinent smokers experienced heightened pain and require more analgesics after surgery, yet the underlying neural mechanisms remain poorly understood. This prospective cohort study identified altered regional brain activity associated with reduced pain thresholds and increased postoperative analgesic requirements in abstinent smokers. We found specific brain regions that were functionally altered and correlated with pain-related outcomes, which mediated the relationship between abstinence and pain-related behaviors. These findings provided novel insights into the supraspinal mechanisms of nicotine withdrawal-induced hyperalgesia and point to potential therapeutic targets for improving postoperative pain management in abstinent smokers.