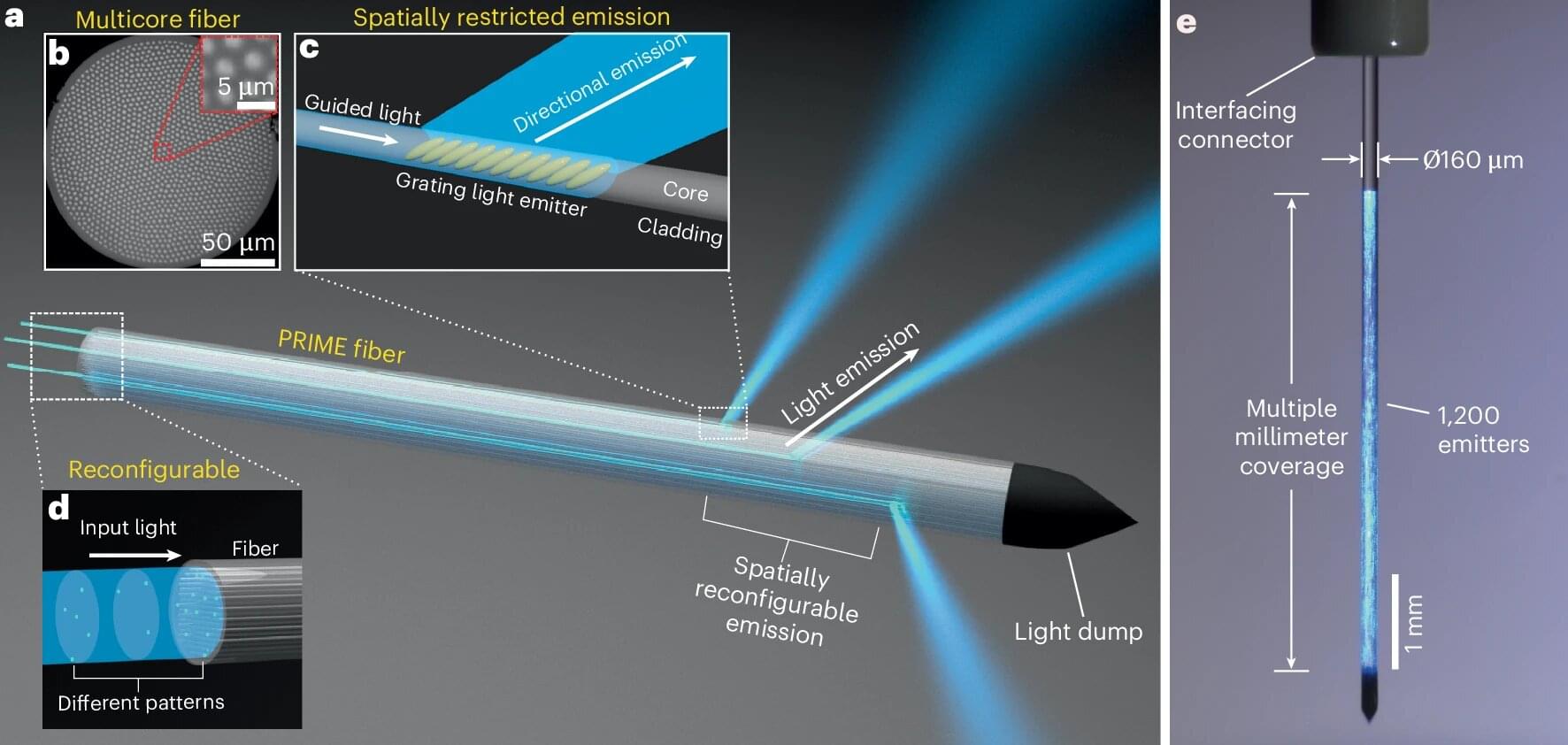

Fiber-optic technology revolutionized the telecommunications industry and may soon do the same for brain research.

A group of researchers from Washington University in St. Louis in both the McKelvey School of Engineering and WashU Medicine have created a new kind of fiber-optic device to manipulate neural activity deep in the brain. The device, called PRIME (Panoramically Reconfigurable IlluMinativE) fiber, delivers multi-site, reconfigurable optical stimulation through a single, hair-thin implant.

“By combining fiber-based techniques with optogenetics, we can achieve deep-brain stimulation at unprecedented scale,” said Song Hu, a professor of biomedical engineering at McKelvey Engineering, who collaborated with the laboratory of Adam Kepecs, a professor of neuroscience and of psychiatry at WashU Medicine.