Early diagnosis and noninvasive monitoring of neurological disorders require sensitivity to elusive cellular-level alterations that emerge much earlier than volumetric changes observable with millimeter-resolution medical imaging.

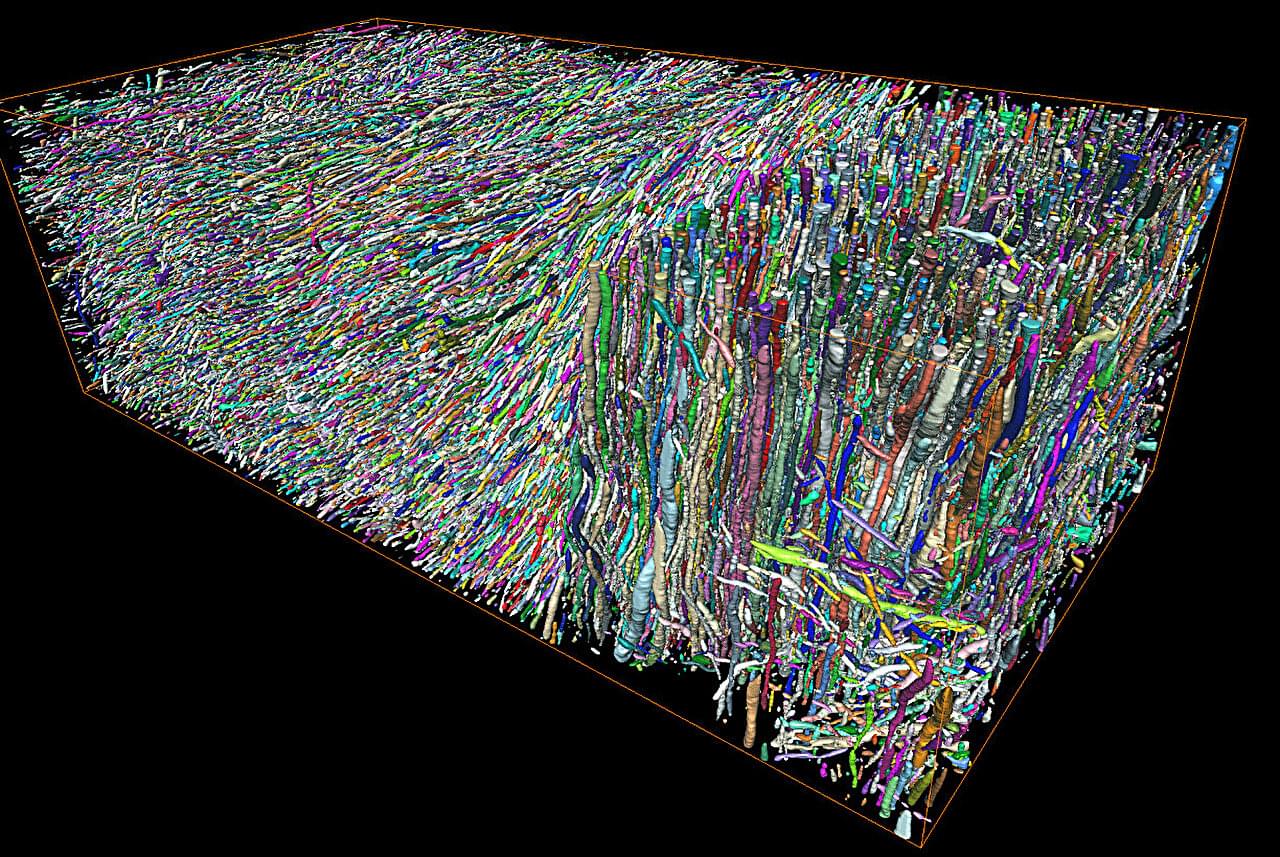

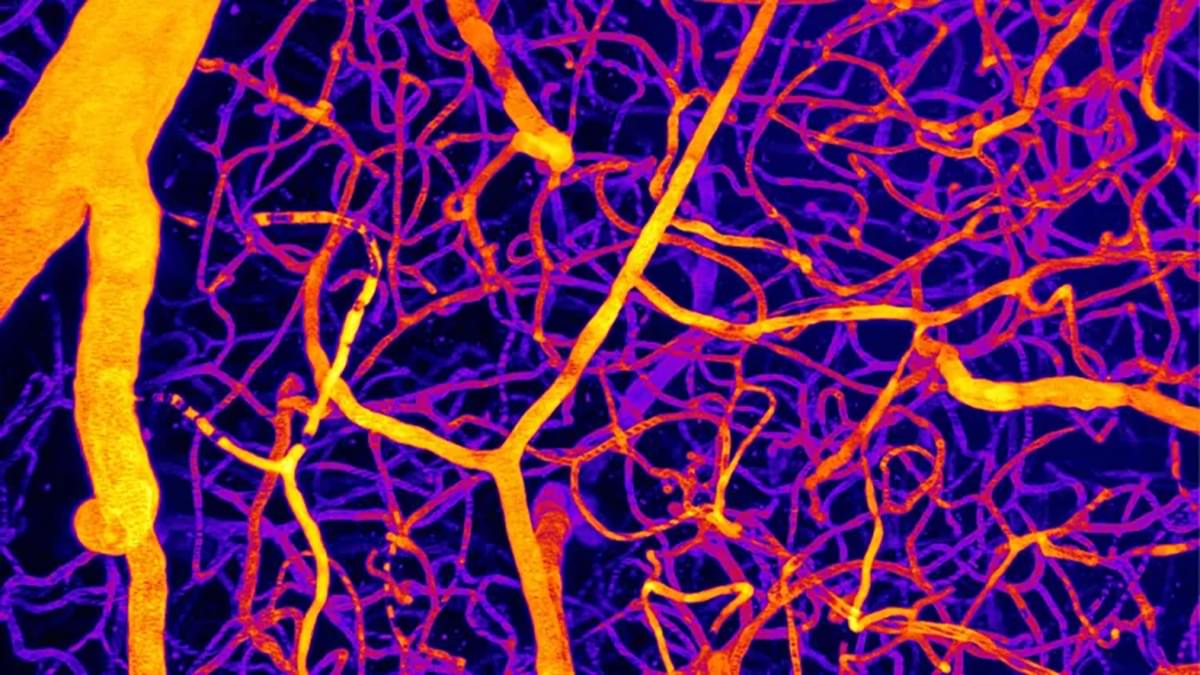

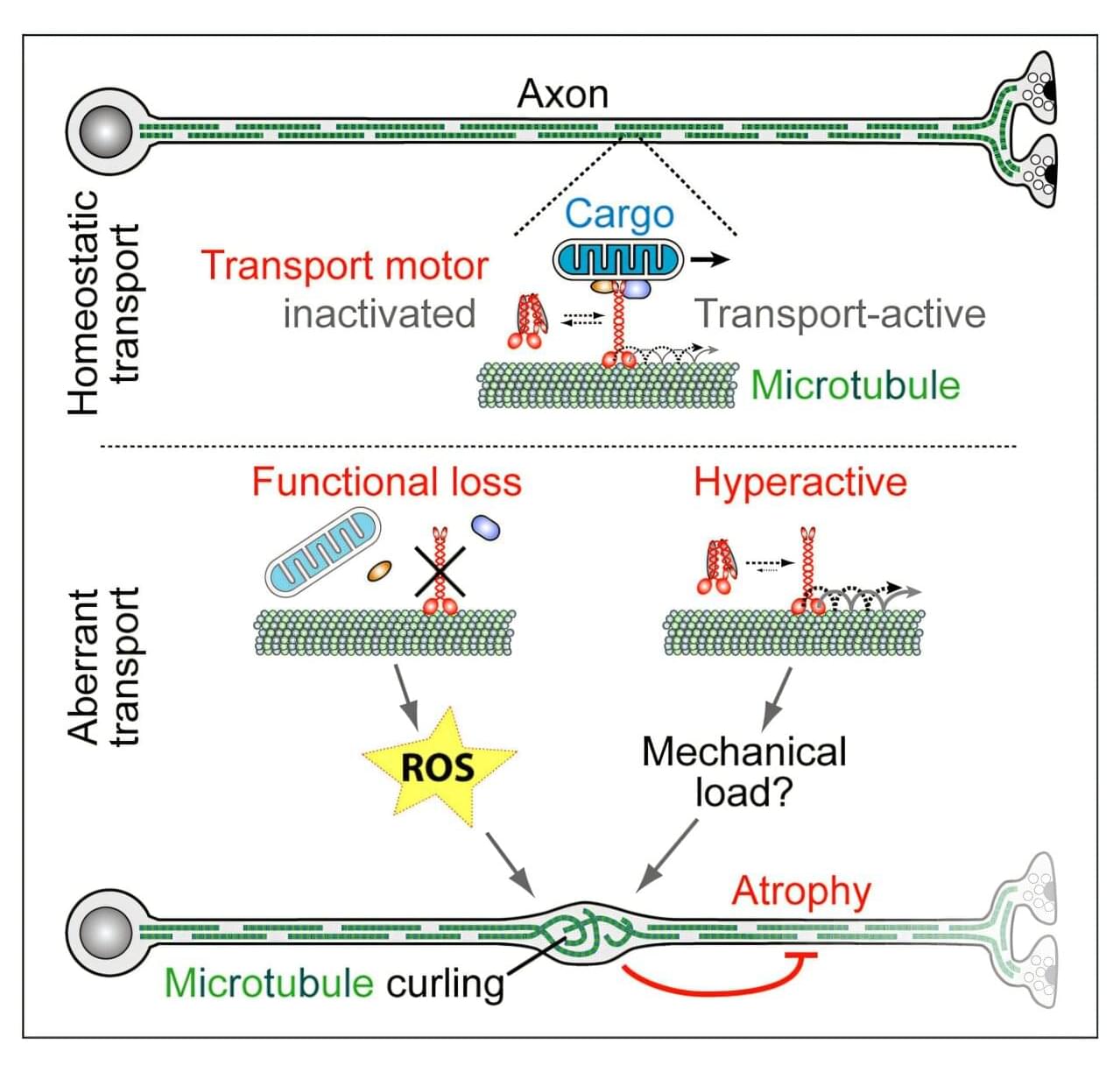

Morphological changes in axons—the tube-like projections of neurons that transmit electrical signals and constitute the bulk of the brain’s white matter—are a common hallmark of a wide range of neurological disorders, as well as normal development and aging.

A study from the University of Eastern Finland (UEF) and the New York University (NYU) Grossman School of Medicine establishes a direct analytical link between the axonal microgeometry and noninvasive, millimeter-scale diffusion MRI (dMRI) signals—diffusion MRI measures the diffusion of water molecules within biological tissues and is sensitive to tissue microstructure.