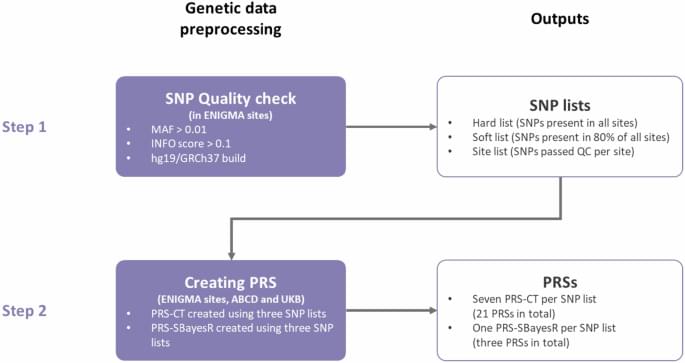

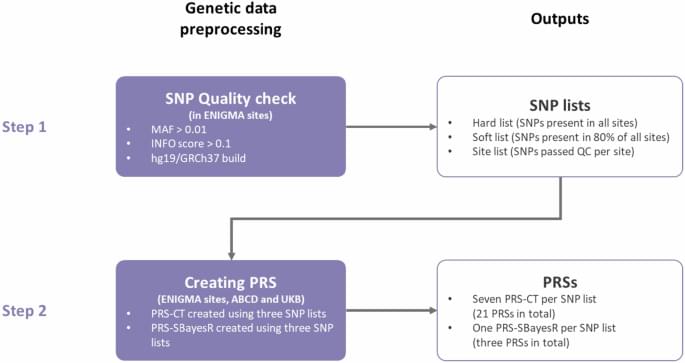

Shen, X., Toenders, Y.J., Han, L.K.M. et al. Mol Psychiatry (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-025-03136-4

Shen, X., Toenders, Y.J., Han, L.K.M. et al. Mol Psychiatry (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-025-03136-4

Their previous work revealed that ILC2s are a major source of a tissue-healing growth factor called amphiregulin and have the capacity to receive neuronal signals that modulate their function and can impact disease progression and recovery.

In the new study, they demonstrated that the tissue-protective function of ILC2s depends on production of a molecule called adrenomedullin 2 (ADM2) from the enteric nervous system; administering the molecule expanded this group of ILC2s and provided therapeutic benefit in a preclinical model of inflammatory bowel disease, whereas loss of ADM2 signaling exacerbated disease due to the lack of these protective cells.

Using a corkscrew, writing a letter with a pen or unlocking a door by turning a key are actions that seem simple but actually require a complex orchestration of precise movements. So, how does the brain do it?

According to a new study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, by researchers from Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Coimbra, the human brain has a specialized system that builds these actions in a surprisingly systematic way.

Analogous to how all of the words in a language can be created by recombining the letters of its alphabet, the full repertoire of human hand actions can be built out of a small number of basic building block movements.

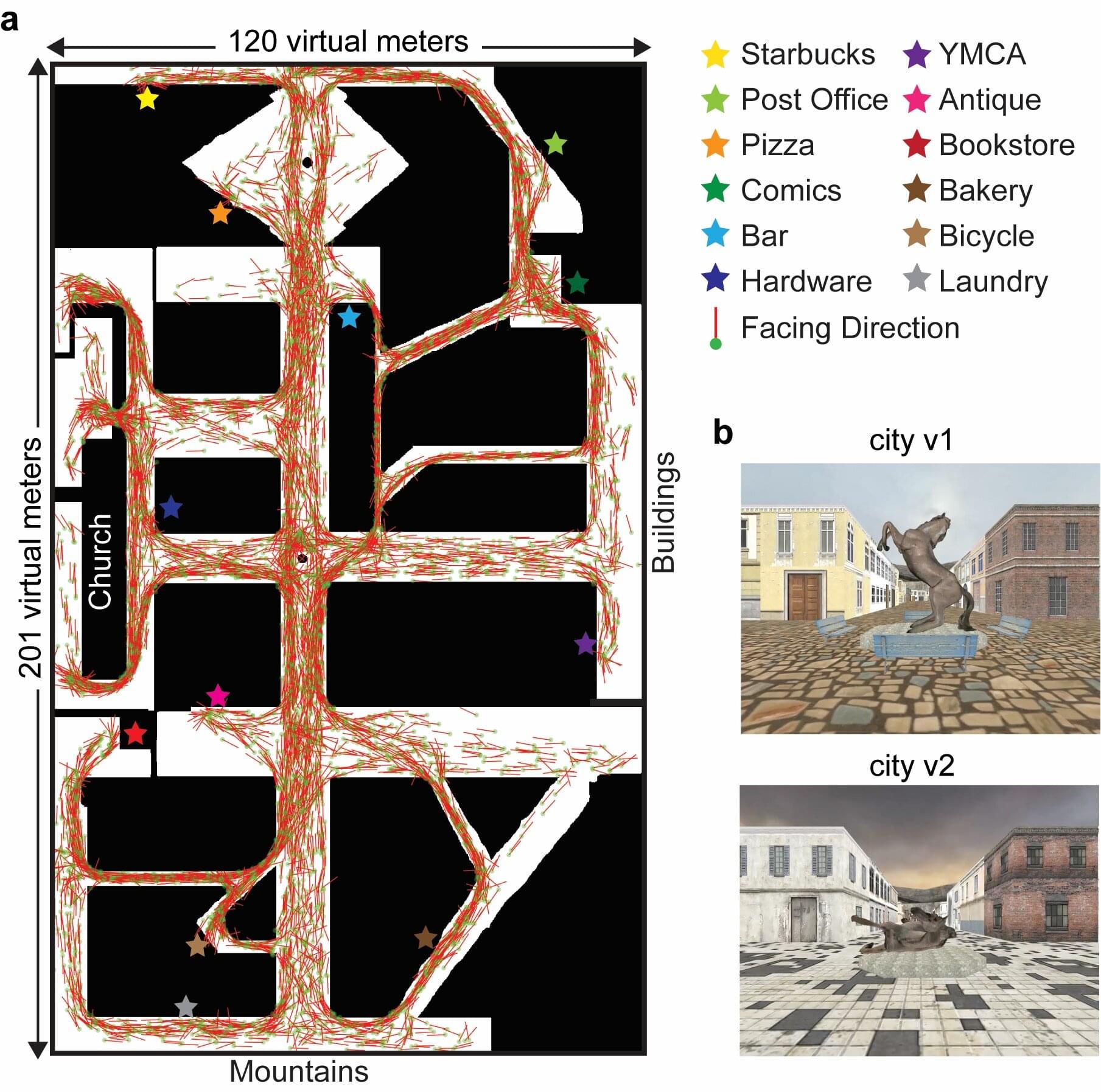

Zhengang Lu and Russell Epstein, from the University of Pennsylvania, led a study to explore how people maintain their sense of direction while navigating naturalistic, virtual reality cities.

As reported in their JNeurosci paper, the researchers collected neuroimaging data while 15 participants performed a taxi-driving task in a virtual reality city. Two brain regions represented a forward-facing direction as people moved around. This neural signal was consistent across variations of the city with different visual features.

The signal was also consistent across different phases of the task (i.e., picking up a passenger versus driving a passenger to their drop-off location) and various locations in the city. Additional analyses suggest that these brain regions represent a broad range of facing directions by keeping track of direction relative to the north–south axis of the environment.

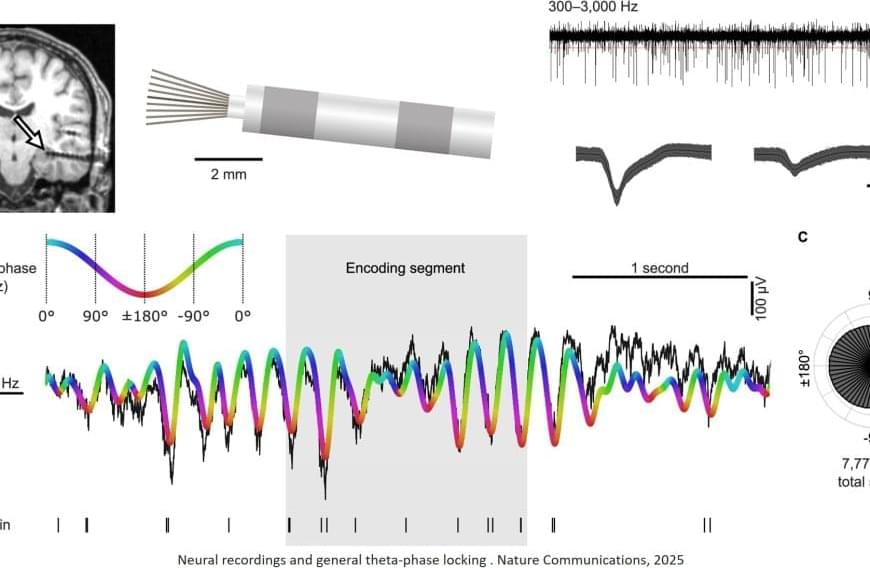

“This suggests that theta-phase locking is a general phenomenon of the human memory system, but does not alone determine successful recall,” says the corresponding author.

While most nerve cells always fired at the same oscillation time, some nerve cells interestingly changed their preferred timing between learning and remembering. “This supports the theory that our brain can separate learning and retrieval processes within a brain wave, similar to members of an orchestra who start playing at different times in a piece of music,” says the author.

A research team has gained new insights into the brain processes involved in encoding and retrieving new memory content. The study is based on measurements of individual nerve cells in people with epilepsy and shows how they follow an internal rhythm. The work has now been published in the journal Nature Communications.

“Similar to members of an orchestra who follow a common beat, the activity of nerve cells appears to be linked to electrical oscillations in the brain, occurring one to ten times per second. The cells prefer to fire at specific times within these brain waves, a phenomenon known as theta-phase locking,” says the first author.

The research team found that the interaction between nerve cells and brain waves is active in both the learning and remembering of new information – specifically in the medial temporal lobe, a central area for human memory. However, in the study on spatial memory, the strength of theta-phase locking of nerve cells during memory formation was independent of whether the test subjects were later able to correctly recall the memory content.