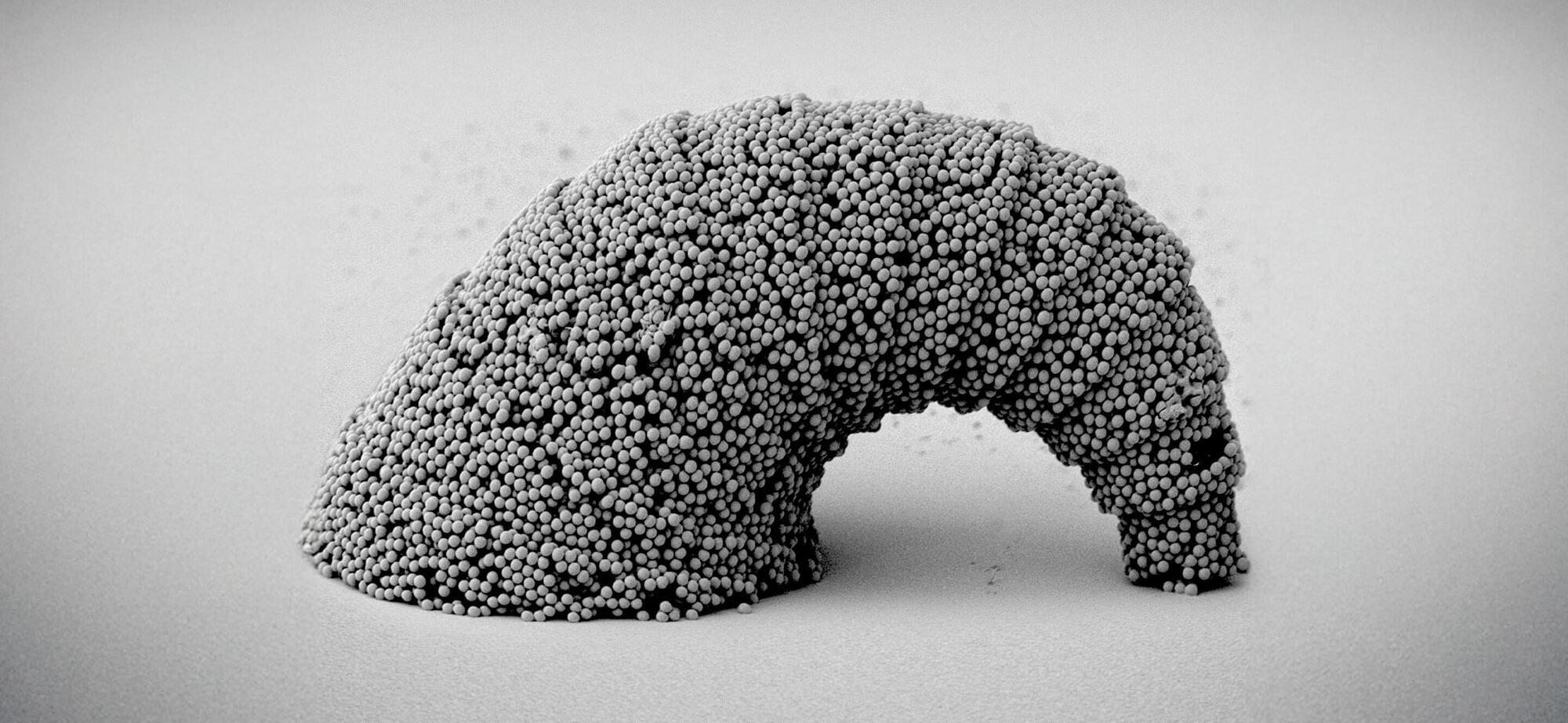

In its first moments, the infant universe was a trillion-degree-hot soup of quarks and gluons. These elementary particles zinged around at light speed, creating a “quark-gluon plasma” that lasted for only a few millionths of a second. The primordial goo then quickly cooled, and its individual quarks and gluons fused to form the protons, neutrons, and other fundamental particles that exist today.

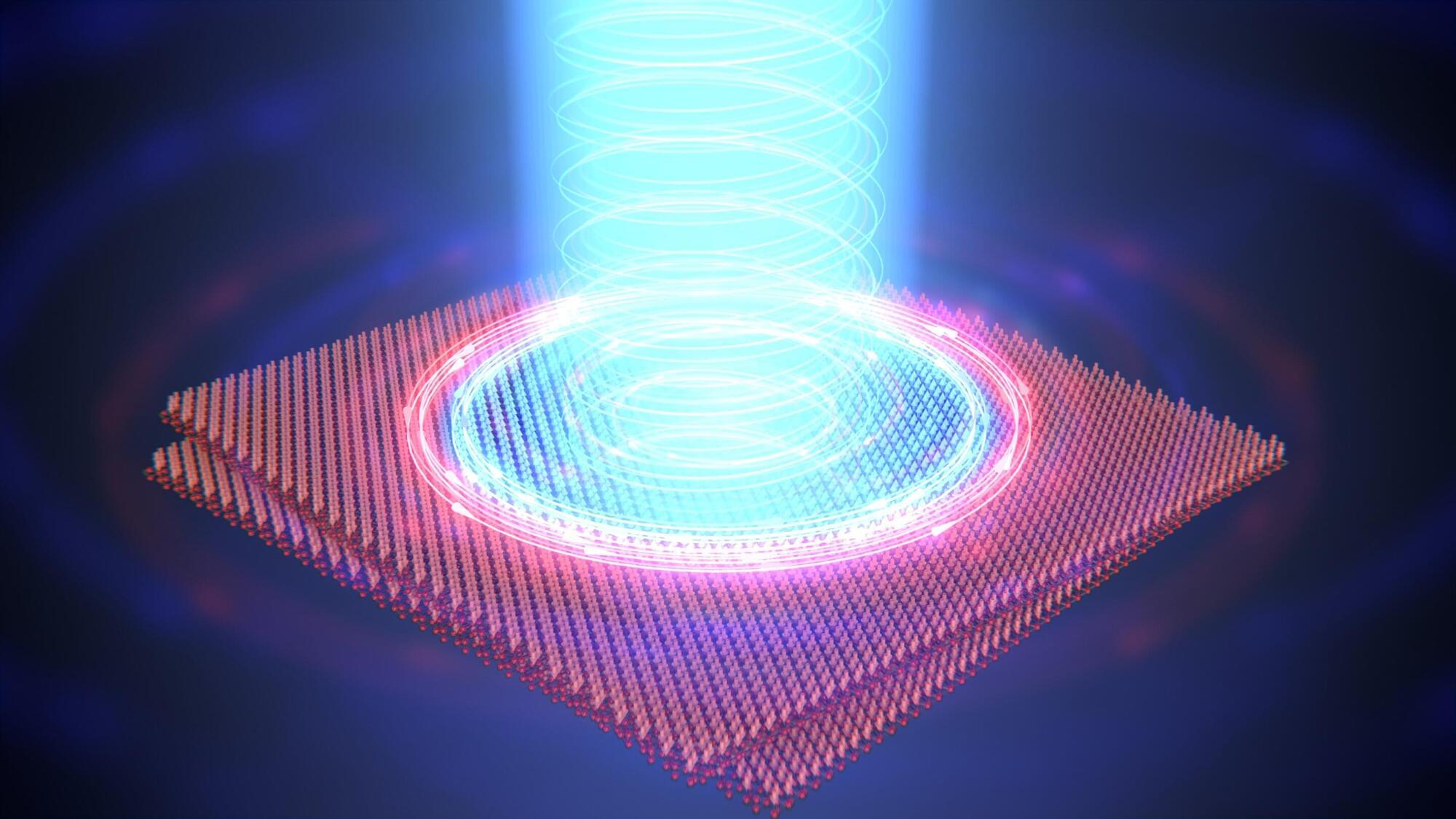

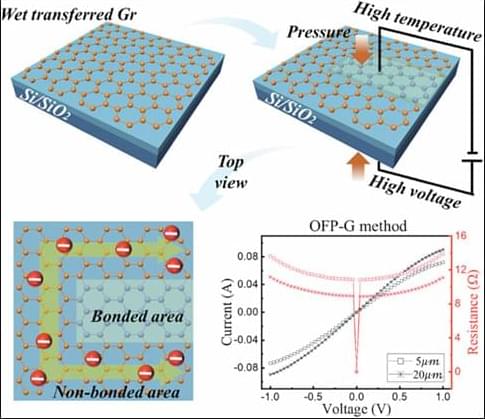

Physicists at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider in Switzerland are recreating quark-gluon plasma (QGP) to better understand the universe’s starting ingredients. By smashing together heavy ions at close to light speeds, scientists can briefly dislodge quarks and gluons to create and study the same material that existed during the first microseconds of the early universe.

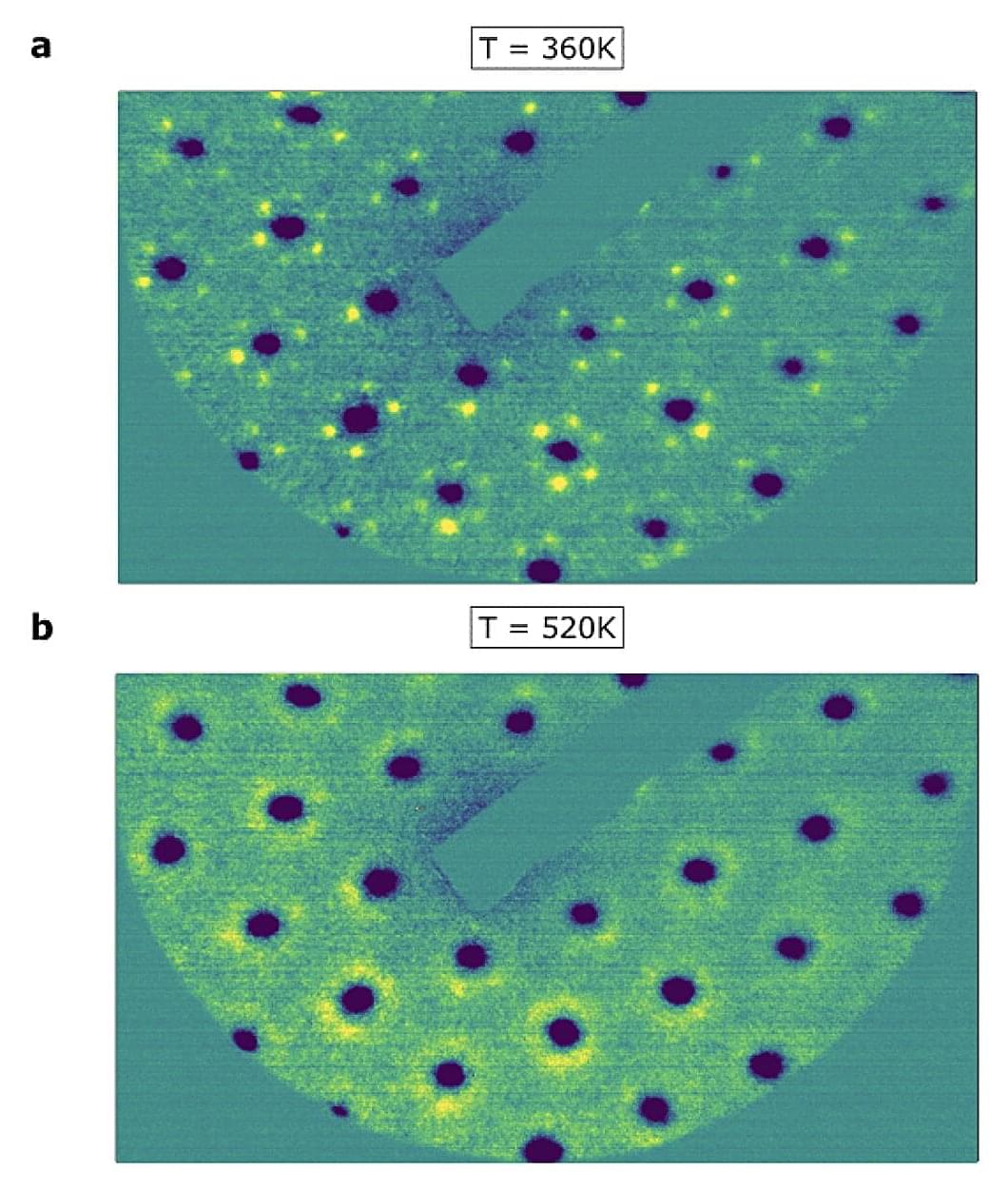

Now, a team at CERN led by MIT physicists has observed clear signs that quarks create wakes as they speed through the plasma, similar to a duck trailing ripples through water. The findings are the first direct evidence that quark-gluon plasma reacts to speeding particles as a single fluid, sloshing and splashing in response, rather than scattering randomly like individual particles.