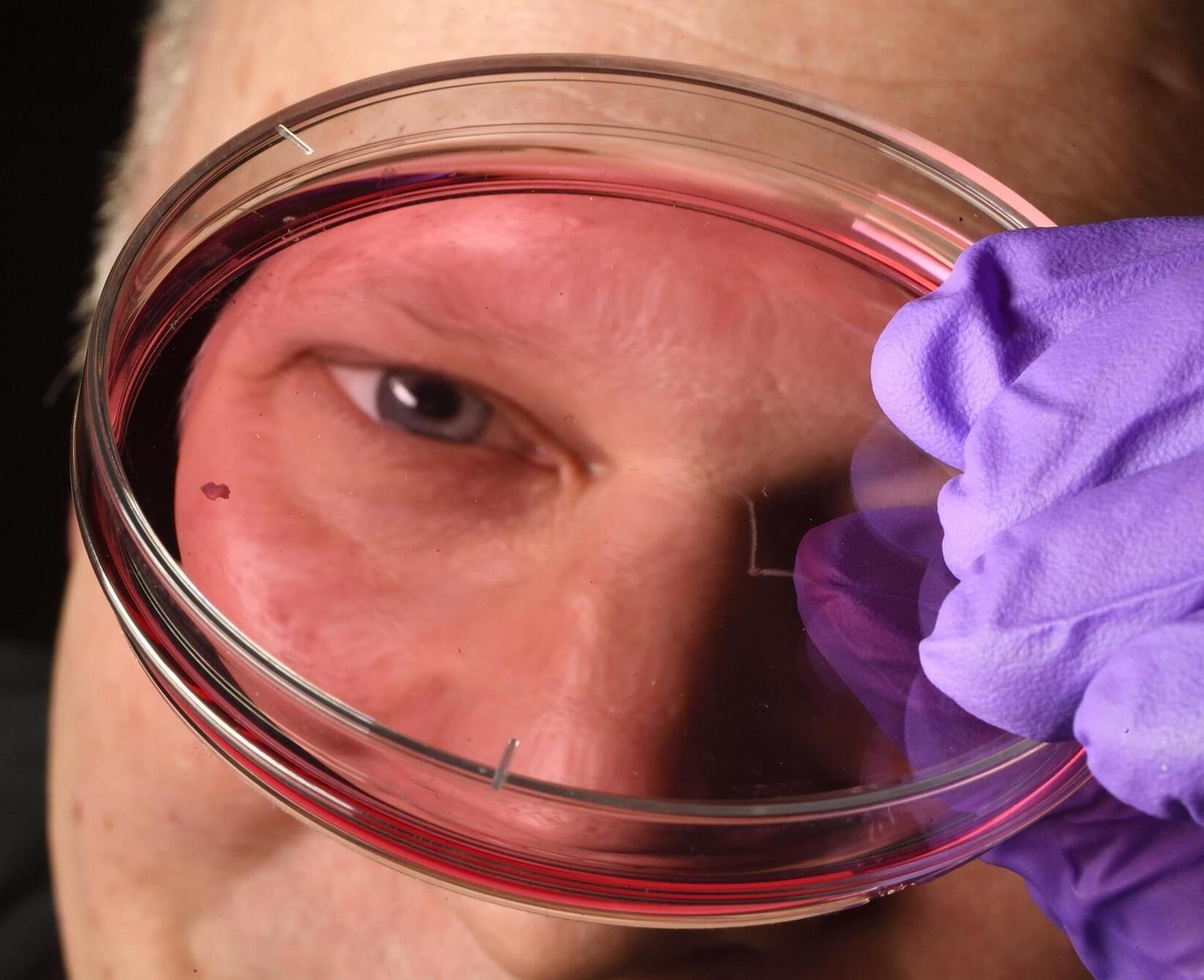

Humans develop sharp vision during early fetal development thanks to an interplay between a vitamin A derivative and thyroid hormones in the retina, Johns Hopkins University scientists have found. The findings could upend decades of conventional understanding of how the eye grows light-sensing cells and could inform new research into treatments for macular degeneration, glaucoma, and other age-related vision disorders. Details of the study, which used lab-grown retinal tissue, are published today in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“This is a key step toward understanding the inner workings of the center of the retina, a critical part of the eye and the first to fail in people with macular degeneration,” said Robert J. Johnston Jr., an associate professor of biology at Johns Hopkins who led the research. “By better understanding this region and developing organoids that mimic its function, we hope to one day grow and transplant these tissues to restore vision.”