Scientists have long suspected connections between heredity and disease, dating back to Hippocrates, who observed certain diseases “ran in families.” However, through the years, scientists have kept getting better at finding ways to also understand the source of those genetic links in the human genome.

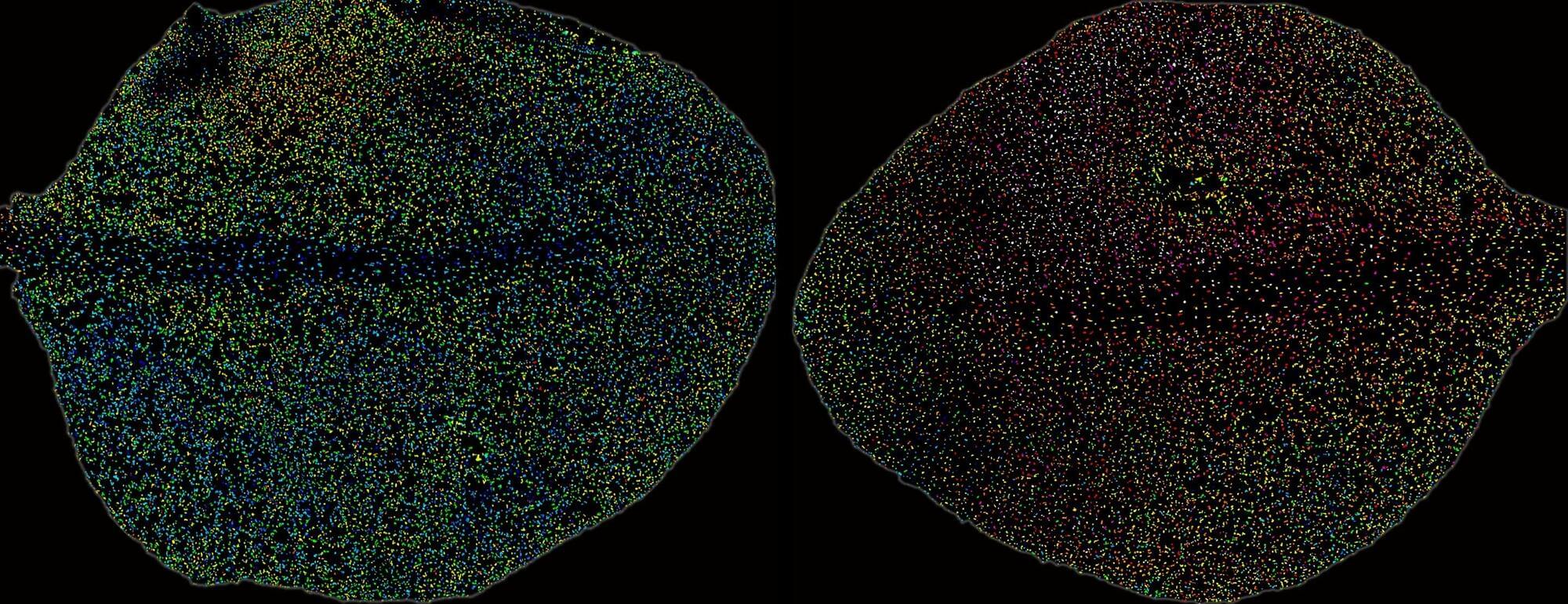

EMBL scientists and collaborators have now developed a tool that goes beyond current single-cell technology by capturing genomic variations and RNA together in the same cell, increasing precision and scalability compared to previous technologies. Able to determine variations in non-coding regions of the genome, this tool transforms how scientists can study the parts of DNA where variations linked to disease are most likely to occur. This single-cell tool, with its high precision and throughput, represents an important advance in drawing correlations between genetic variants and disease.

“This has been a long-standing problem, as current single-cell methods to study DNA and RNA in the same cell have had limited throughput, lacked sensitivity, and are complicated,” said Dominik Lindenhofer, the lead author on a new paper about SDR-Seq published in Nature Methods and a postdoctoral fellow in EMBL’s Steinmetz Group.