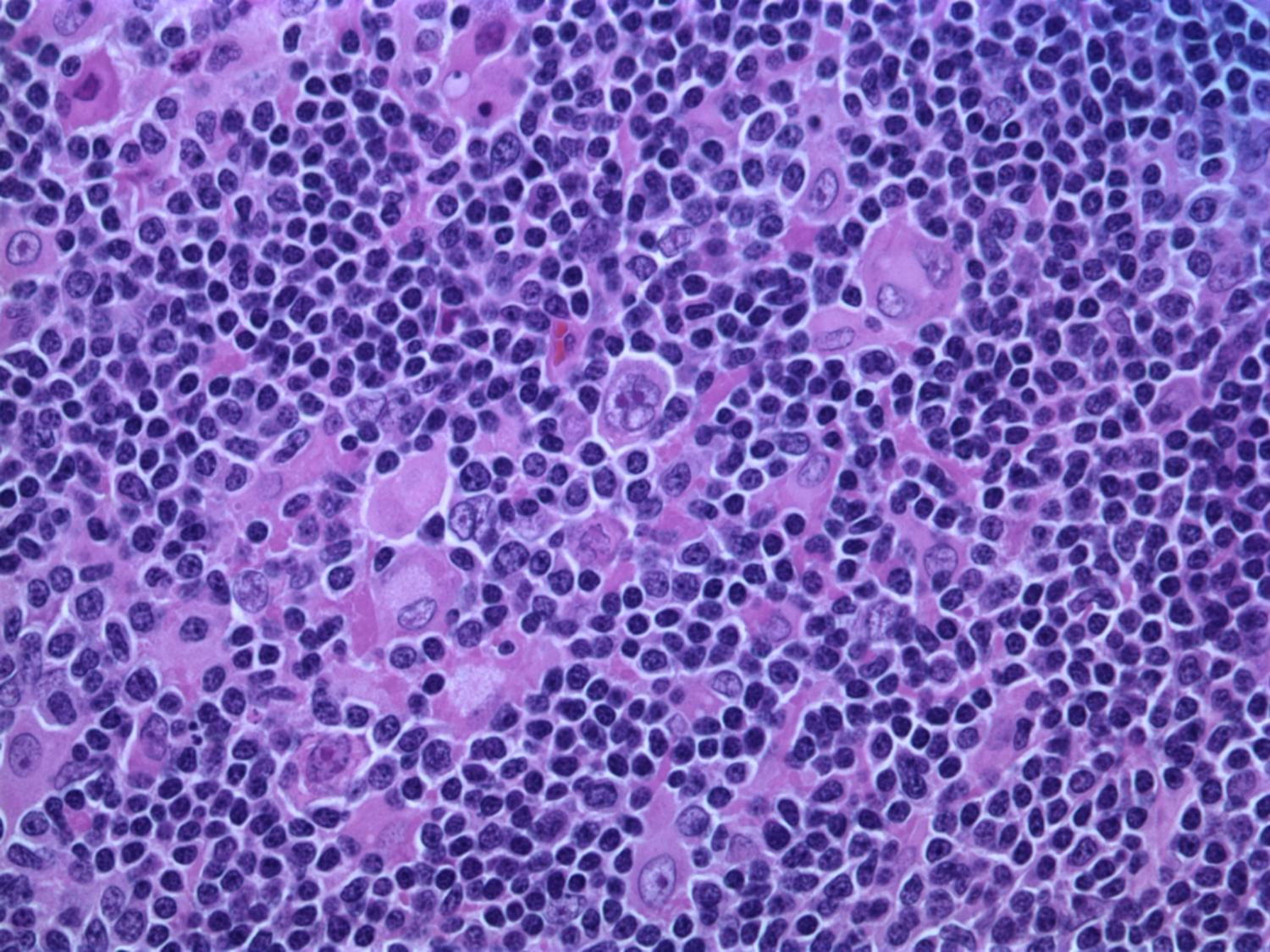

In a study published in Neuron, a research team at the Department of Neurology at Massachusetts General Hospital, aimed to understand how immune cells of the brain, called microglia, contribute to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology. It’s known that subtle changes, or mutations, in genes expressed in microglia are associated with an increased risk for developing late-onset AD.

The study focused on one such mutation in the microglial gene TREM2, an essential switch that activates microglia to clean up toxic amyloid plaques (abnormal protein deposits) that build up between nerve cells in the brain. This mutation, called T96K, is a “gain-of-function” mutation in TREM2, meaning it increases TREM2 activation and allows the gene to remain super active.

The researchers explored how this mutation impacts microglial function to increase risk for AD. The team generated a mutant mouse model carrying the mutation, which was bred with a mouse model of AD to have brain changes consistent with AD. They found that in female AD mice exclusively, the mutation strongly reduced the capability of microglia to respond to toxic amyloid plaques, making these cells less protective against brain aging.