Cell-to-cell communication through nanosized particles, working as messengers and carriers, can now be analyzed in a whole new way, thanks to a new method involving CRISPR gene-editing technology. The particles, known as small extracellular vesicles (sEVs), play an important role in the spread of disease and as potential drug carriers. The newly developed system, named CIBER, enables thousands of genes to be studied at once, by labeling sEVs with a kind of RNA “barcode.” With this, researchers hope to find what factors are involved in sEV release from host cells. This will help advance our understanding of basic sEV biology and may aid in the development of new treatments for diseases, such as cancer.

Your body “talks” in more ways than one. Your cells communicate with each other, enabling your different parts to function as one team. However, there are still many mysteries surrounding this process. Extracellular vesicles (EVs), small particles released by cells, were previously thought to be useless waste. However, in recent decades they have been dramatically relabeled as very important particles (VIPs), due to their association with various diseases, including cancer, neurodegenerative diseases and age-related diseases.

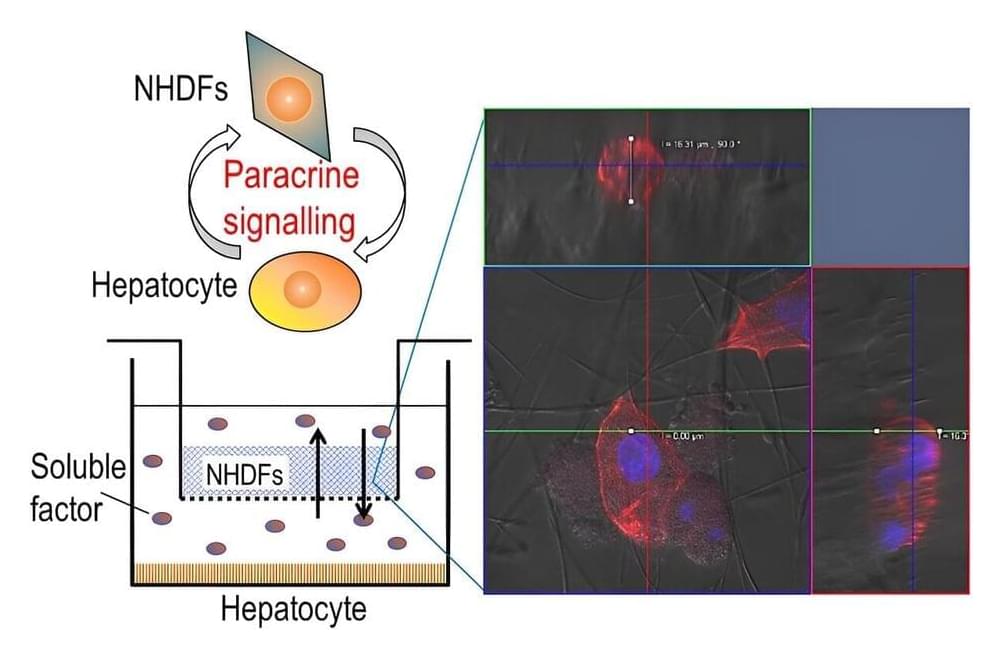

Small EVs have been found to play a key role in cell-to-cell communication. Depending on what “cargo” they carry from their host cell (which can include RNA, proteins and lipids), sEVs can help maintain normal tissue functions or can further the spread of diseases. Because of this, researchers are interested in how sEVs form and are released. However, separating sEVs from other molecules and identifying the factors which lead to their release is both difficult and time-consuming with conventional methods. So, a team in Japan has developed a new technique.