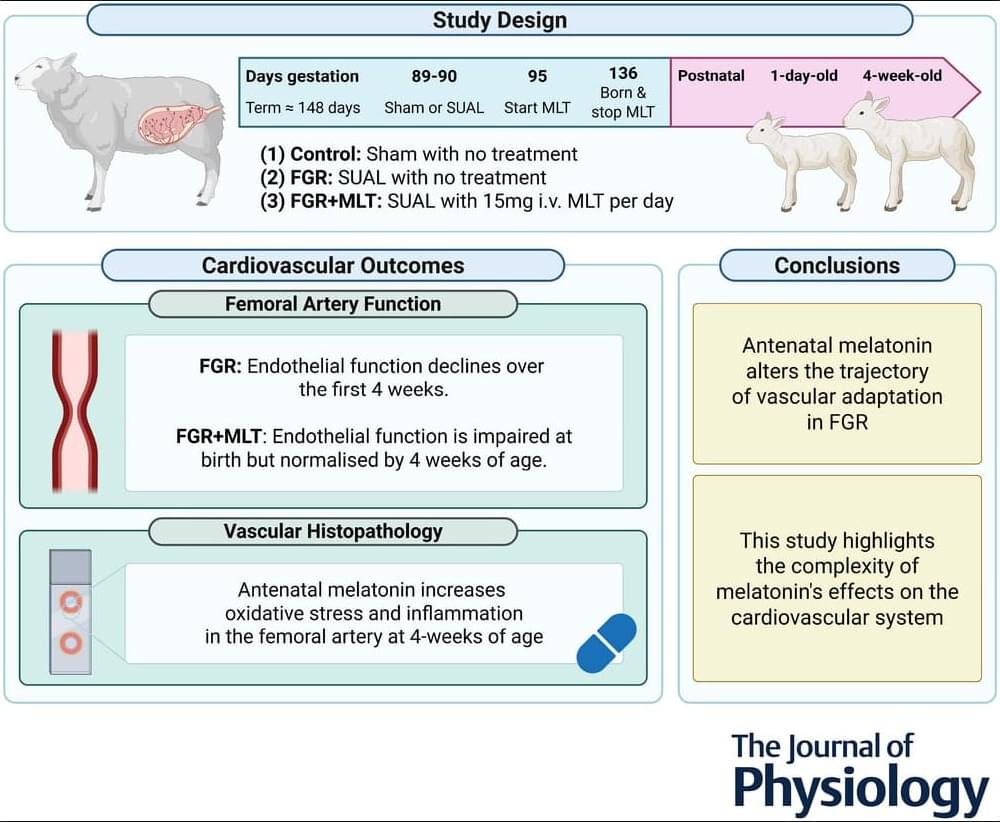

Recent Research by Charmaine R. Rock of Hudson Institute of Medical Research et al. examines antenatal melatonin for cardiovascular deficits in fetal growth restriction 🫀 💊

🔗 📜 Read the study here.

The results of the present study indicate that melatonin has the potential to mitigate the progressive development of impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilatation in growth-restricted lambs. However, this benefit is associated with transient impairment of endothelial function on the first day of life. It would be prudent to investigate the physiological implications of this early vascular dysfunction during the critical period of cardiovascular adaptation to postnatal life. Adjustments to the antenatal melatonin treatment regime, such as tapering the dose before and after birth, could be explored to support a smoother cardiovascular transition on the first day of life.

Additionally, because the present study was conducted up to 4 weeks of age, equivalent to an ∼1-year-old human infant, extending the study outcomes into adulthood is important to determine whether endothelial function is sustained or continues to improve with age, potentially achieving full restoration to the relaxation abilities observed in control lambs. Furthermore, given that functional assessment of the carotid artery was not possible in our study, future research should include such testing to provide a more comprehensive understanding of how FGR impacts vascular function.

The present study provides novel insight into the short-and longer-term, and region-specific impact of melatonin on the cardiovascular system. Our findings demonstrate that, although antenatal melatonin improves the contribution of NO to endothelium-dependent vasodilatation in the femoral artery of newborn FGR+MLT lambs, it is accompanied by an overall reduction in femoral endothelium-dependent vasodilatory capacity. Notably, this reduction in endothelial function is transient and improves by 4 weeks of age, which contrasts with the progressive impairment of endothelial function seen in untreated FGR lambs. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed elevated oxidative stress and inflammatory markers in the femoral artery of 4-week-old FGR+MLT lambs.