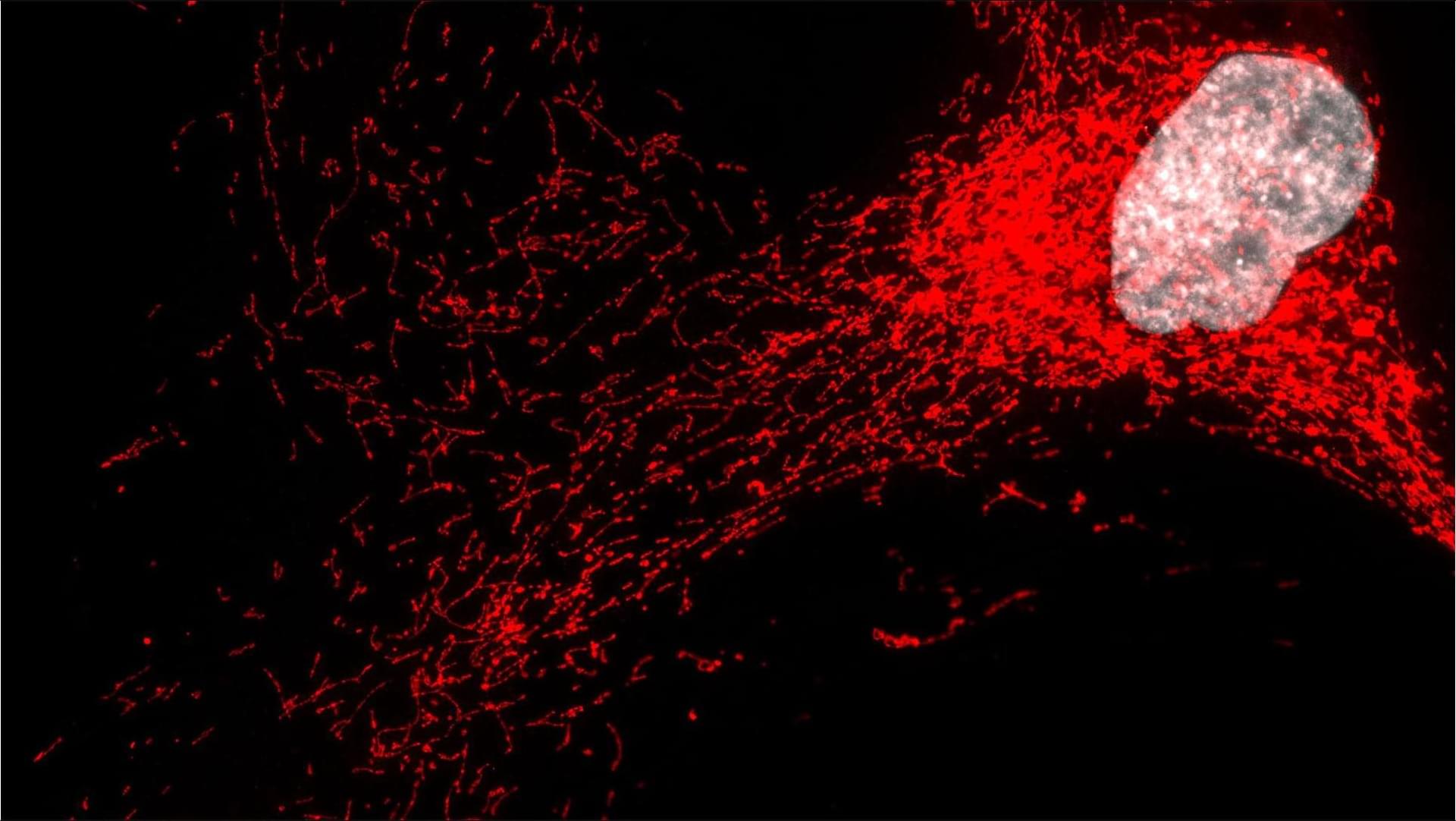

Now online! Melanoma cells escape immune surveillance by releasing MHC-antigen-loaded large EVs, known as melanosomes, that directly engage and impair CD8+ T cell receptors.

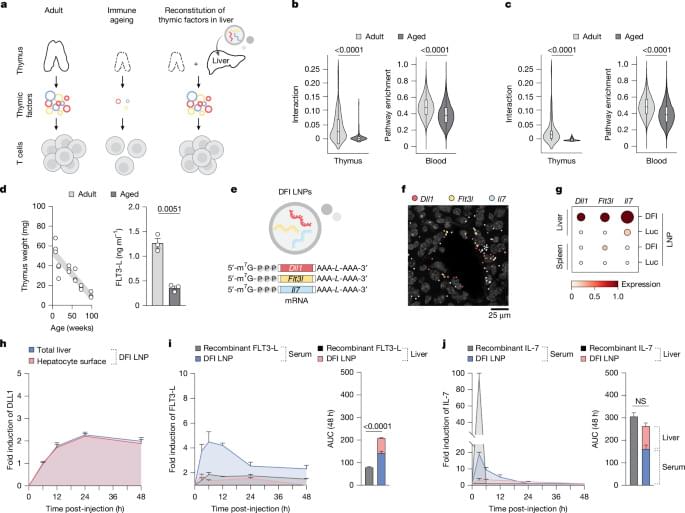

Now online! Melanoma cells and melanosomes had distinct MHC class I ligandome profiles (Figure 4 G), but a substantial proportion of the melanosome-derived peptide repertoire overlapped with that of the parent cells (83.8%), implying derivation from the total cellular ligandome (Figure 4 G). Pathway enrichment analysis of the immunopeptidome landscape revealed a positive correlation between pathways enriched in cells and their corresponding melanosomes, with substantial overlaps in functional categories such as class I MHC-mediated antigen processing and presentation, DNA repair, and cell cycle regulation (Figures 4 H and 4I). Given the observed MHC class I-dependent, peptide-specific suppression of CD8+ T cell activity by melanosomes, we hypothesized that melanosomes present immunogenic peptides. Indeed, we have identified 25 tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) in melanosome samples (Figure 4 J) with high-confidence peptide identifications (Figure 4 K). These TAAs are predicted to bind a variety of HLA alleles with high affinity. Strikingly, the majority of these peptides were also detected in the corresponding melanoma cell samples (Figure 4 J). Notably, melanosomes exhibited a statistically significant enrichment in TAA presentation compared with melanoma cells, regardless of IFNγ treatment (Figure 4 L).

Finally, we used whole-exome sequencing to generate a custom proteomic database for proteogenomic analysis of neopeptides/neoantigens. This approach identified three mutation-derived neoantigens within the human melanosome immunopeptidome, two of which were also present in the cellular MHC class I repertoire (Figures 4 M and 4N). Importantly, we analyzed the murine B16F10 cells and secreted melanosome immunopeptidomic data, which recapitulated most of our findings in human cells (Figures S4 A–S4J). Together, these findings suggest that melanosomes, by carrying immunogenic peptides, including TAAs and neoantigens, compete with melanoma cells for CD8+ T cell recognition, thereby contributing to their immunomodulatory effects.