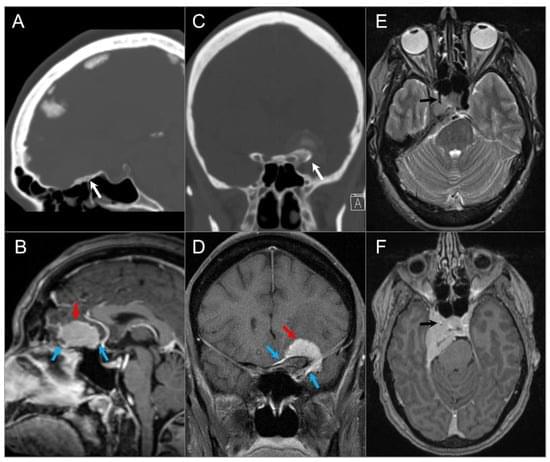

The skull base provides a platform for supporting the brain while serving as a conduit for major neurovascular structures. In addition to malignant lesions originating in the skull base, there are many benign entities and developmental variants that may simulate disease. Therefore, a basic understanding of the relevant embryology is essential. Lesions centered in the skull base can extend to the adjacent intracranial and extracranial compartments; conversely, the skull base can be secondarily involved by primary extracranial and intracranial disease. CT and MRI are the mainstay imaging methods and are complementary in the evaluation of skull base lesions. Advances in cross-sectional imaging have been crucial in the management of patients with skull base pathology, as this represents a complex anatomical area that is hidden from direct clinical exam.