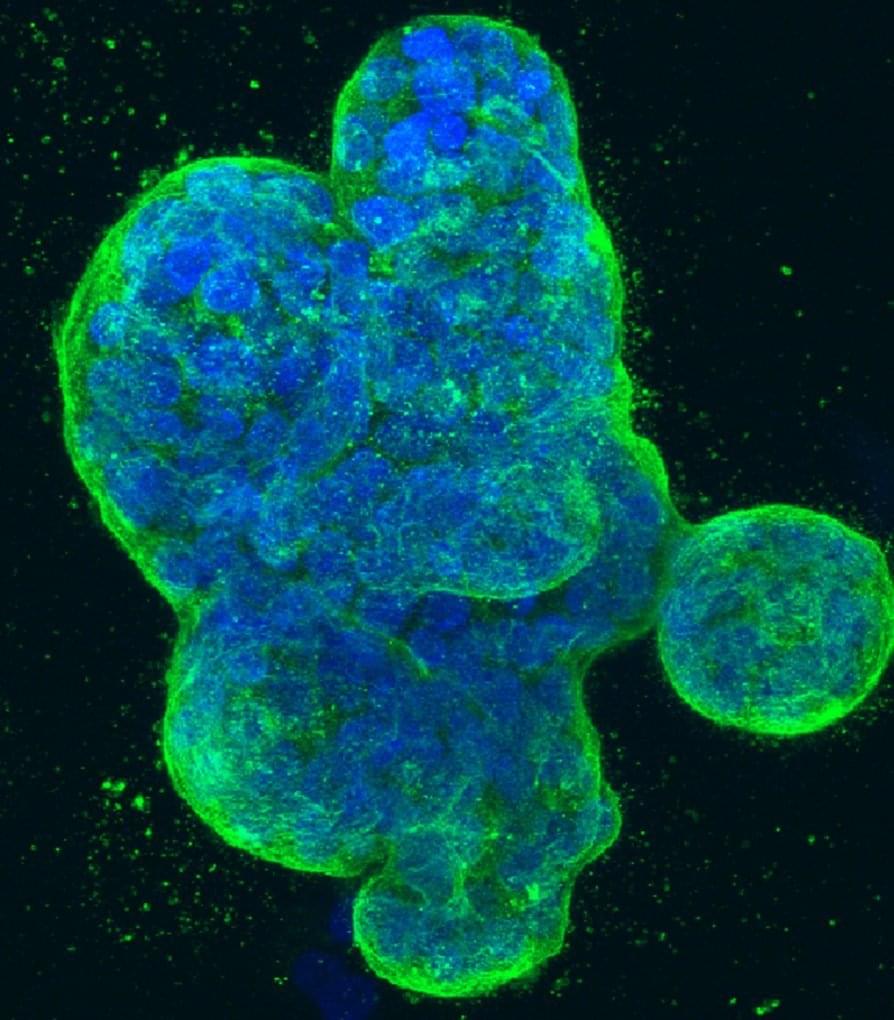

Research led by Suresh Alahari, Ph.D., Professor of Biochemistry at LSU Health New Orleans schools of Medicine and Graduate Studies, suggests a combination of drugs already approved by the FDA for other cancers may be effective in treating chemo-resistant triple-negative breast cancer. The results are published in Molecular Cancer.

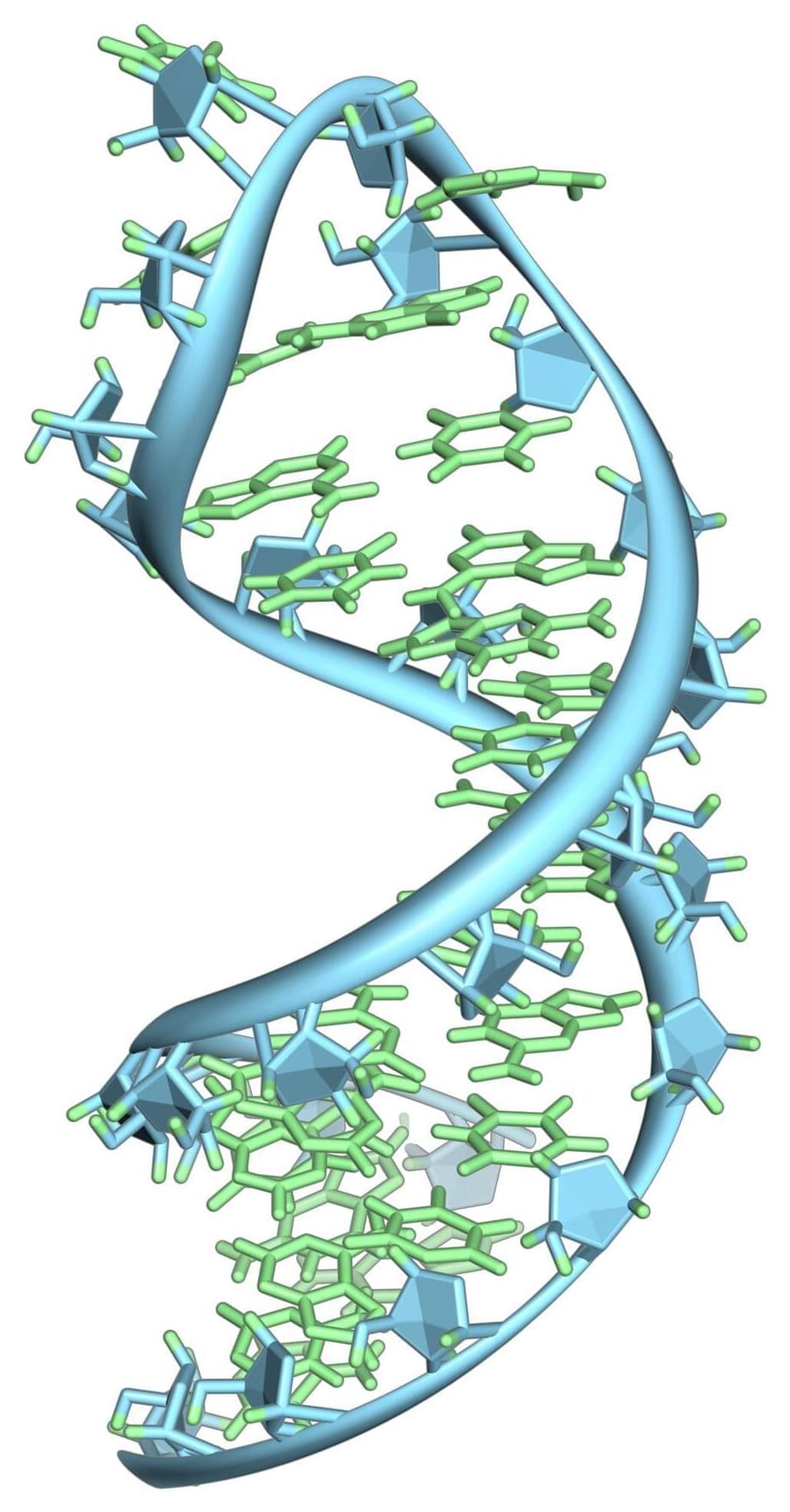

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) tumors lack estrogen receptors, progesterone receptors, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). A subtype representing 12–55% of triple-negative breast cancer tumors has androgen receptors (AR). Since androgen receptors stimulate tumor cell progression in estrogen receptor-negative breast cancers, they have become a target of triple-negative breast cancer therapy. As well, since a substantial number of patients with triple-negative breast cancer develop resistance to paclitaxel, the FDA-approved chemotherapeutic agent for triple-negative breast cancer, new therapeutic approaches are needed.

Working in a mouse model and tissue from patients with triple-negative breast cancer, the research team screened 133 FDA-approved drugs that have a therapeutic effect against androgen receptor cells. They found that ceritinib, an FDA-approved drug for lung cancers, efficiently inhibited the growth of androgen receptor triple-negative breast cancer cells. To improve the response, they also selected enzalutamide, an FDA-approved androgen receptor antagonist for prostate cancer treatment.