The FDA has yet to approve any drugs for life extension. But biotech company Loyal is now a step closer to bringing one to market—for dogs.

The major phenotypes of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) include ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), which cause debilitating symptoms, including bloody diarrhea, abdominal discomfort, and fever. Patients require life-long immunosuppressive medications, which cause adverse side effects as additional morbidity factors. However, IBD is initiated and perpetuated by inflammatory cytokines, and given that in patients with IBD myeloid lineage leukocytes are elevated with activation behavior and release inflammatory cytokines, selective depletion of elevated granulocytes and monocytes by granulomonocytapheresis is a relevant therapeutic option for IBD patients.

Therefore, a column filled with specially designed beads as granulomonocytapheresis carriers for selective adsorption of myeloid lineage leukocytes (Adacolumn) has been applied to treat patients with active IBD.

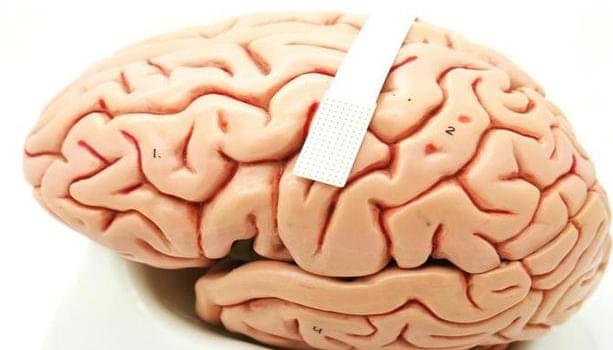

A speech prosthetic developed by a collaborative team of Duke neuroscientists, neurosurgeons, and engineers can translate a person’s brain signals into what they’re trying to say.

Appearing Nov. 6 in the journal Nature Communications, the new technology might one day help people unable to talk due to neurological disorders regain the ability to communicate through a brain-computer interface.

“There are many patients who suffer from debilitating motor disorders, like ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) or locked-in syndrome, that can impair their ability to speak,” said Gregory Cogan, Ph.D., a professor of neurology at Duke University’s School of Medicine and one of the lead researchers involved in the project. “But the current tools available to allow them to communicate are generally very slow and cumbersome.”

Join us on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/MichaelLustgartenPhD

Discount Links:

At-Home Metabolomics: https://www.iollo.com?ref=michael-lustgarten.

Use Code: CONQUERAGING At Checkout.

Epigenetic, Telomere Testing: https://trudiagnostic.com/?irclickid=U-s3Ii2r7xyIU-LSYLyQdQ6…M0&irgwc=1

Use Code: CONQUERAGING

NAD+ Quantification: https://www.jinfiniti.com/product/intracellular-nad-test/

Use Code: ConquerAging At Checkout.

Oral Microbiome: https://www.bristlehealth.com/?ref=michaellustgarten.

Enter Code: ConquerAging.

At-Home Blood Testing (SiPhox Health): https://getquantify.io/mlustgarten.

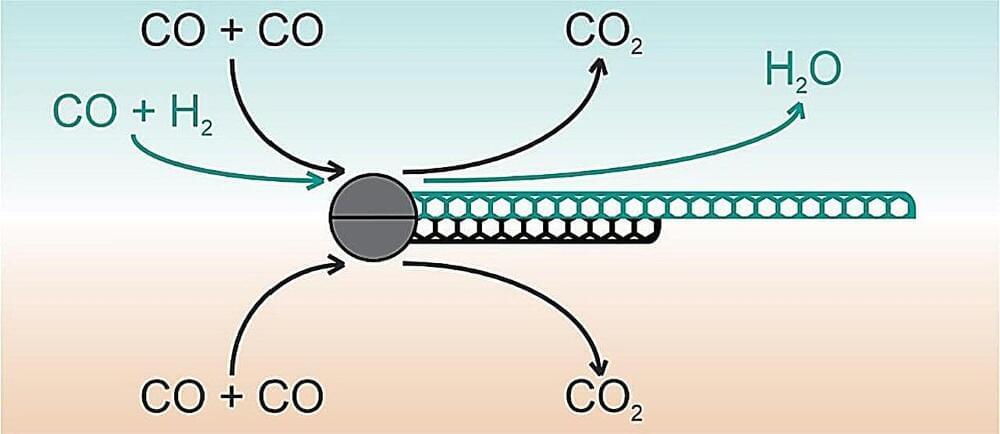

Skoltech scientists have found a way to improve the most widely used technology for producing single-walled carbon nanotube films—a promising material for solar cells, LEDs, flexible and transparent electronics, smart textiles, medical imaging, toxic gas detectors, filtration systems, and more. By adding hydrogen gas along with carbon monoxide to the reaction chamber, the team managed to almost triple carbon nanotube yield compared with when other growth promoters are used, without compromising quality.

Until now, low yield has been the bottleneck limiting the potential of that manufacturing technology, otherwise known for high product quality. The study has been published in the Chemical Engineering Journal.

Although that is not how they’re really made, conceptually, nanotubes are a form of carbon where sheets of atoms in a honeycomb arrangement—known as graphene—are seamlessly rolled into hollow cylinders.

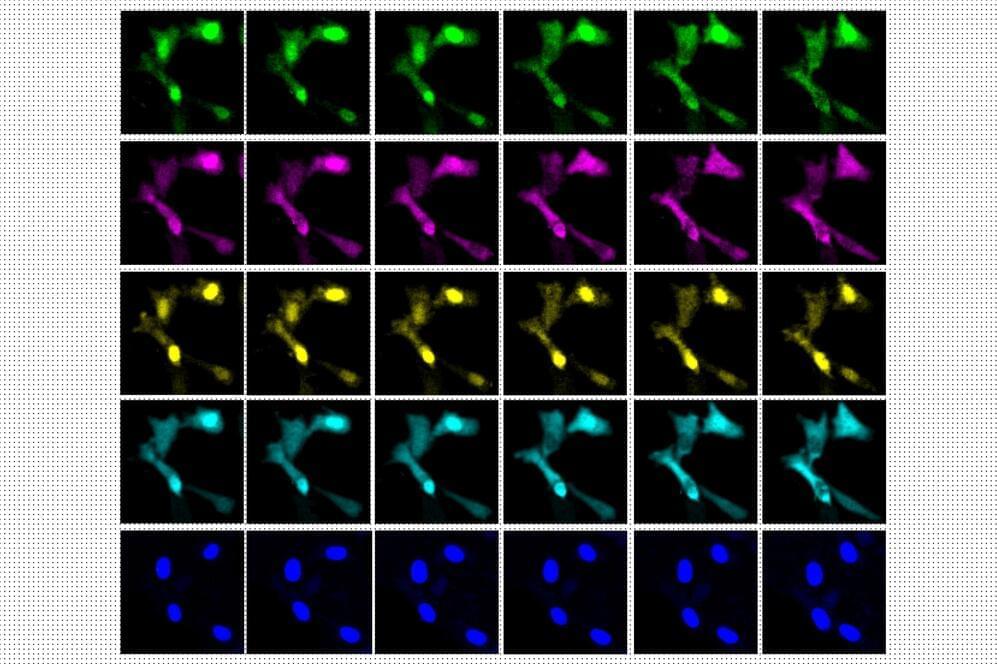

Living cells are bombarded with many kinds of incoming molecular signal that influence their behavior. Being able to measure those signals and how cells respond to them through downstream molecular signaling networks could help scientists learn much more about how cells work, including what happens as they age or become diseased.

Right now, this kind of comprehensive study is not possible because current techniques for imaging cells are limited to just a handful of different molecule types within a cell at one time. However, MIT researchers have developed an alternative method that allows them to observe up to seven different molecules at a time, and potentially even more than that.

“There are many examples in biology where an event triggers a long downstream cascade of events, which then causes a specific cellular function,” says Edward Boyden, the Y. Eva Tan Professor in Neurotechnology. “How does that occur? It’s arguably one of the fundamental problems of biology, and so we wondered, could you simply watch it happen?”

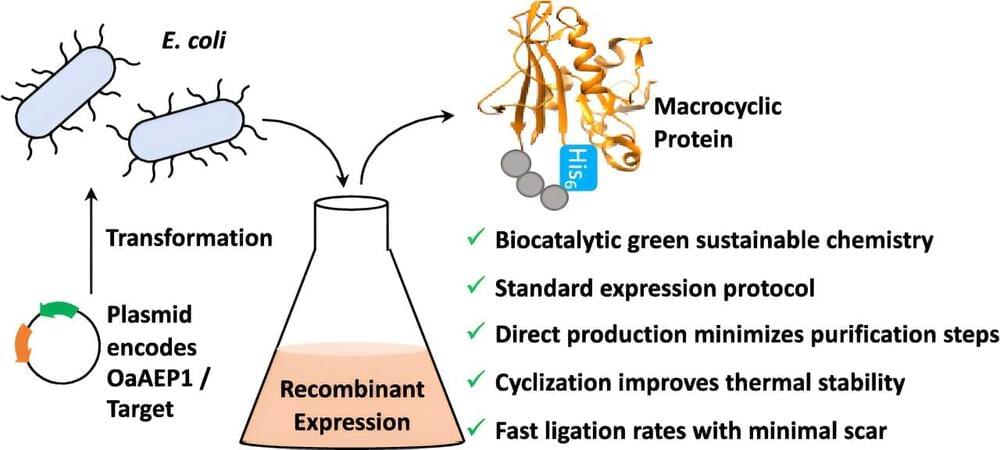

Scientists at the University of Bath have used nature as inspiration in developing a new tool that will help researchers develop new pharmaceutical treatments in a cleaner, greener, and less expensive way.

Drug treatments often work by binding to proteins involved in disease and blocking their activity, which either reduces symptoms or treats the disease.

Rather than using conventional small molecules as drugs, which are not well suited to blocking interactions between proteins, the pharmaceutical industry is now investigating the potential of making drugs using small proteins known as ‘peptides,’ which work in a similar way.

As researchers, developers, policymakers and others grapple with navigating socially beneficial advanced technology transitions — especially those associated with artificial intelligence, DNA-based technologies, and quantum technologies — there are valuable lessons to be drawn from nanotechnology. These lessons underscore an urgent need to foster collaboration, engagement and partnerships across disciplines and sectors, together with bringing together people, communities, and organizations with diverse expertise, as they work together to realize the long-term benefits of transformative technologies.