Category: 3D printing – Page 42

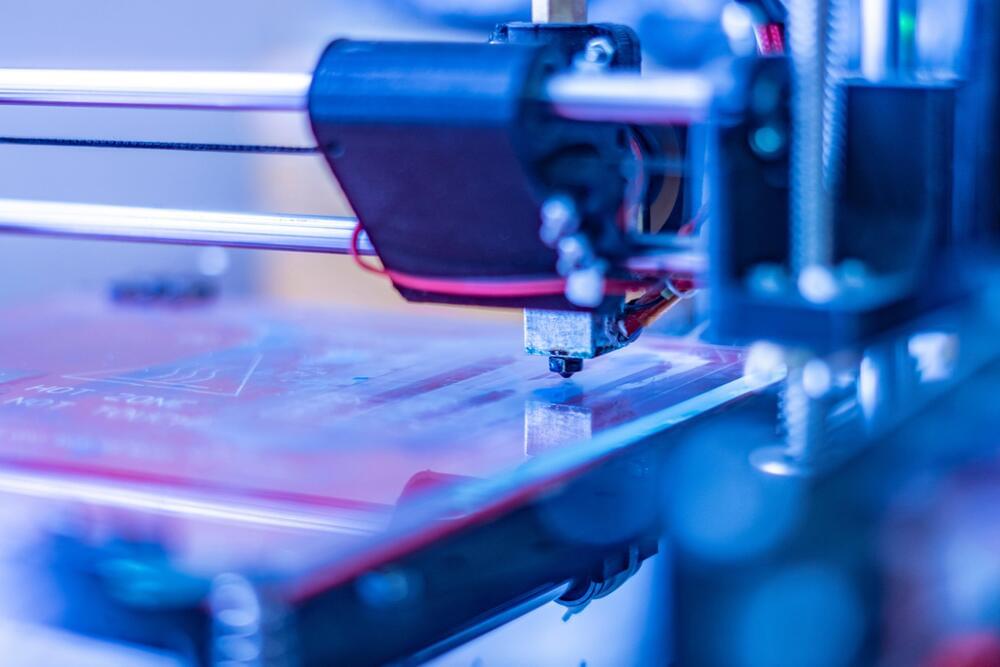

Machine-learning model monitors and adjusts 3D printing process to correct errors in real-time

Scientists and engineers are constantly developing new materials with unique properties that can be used for 3D printing, but figuring out how to print with these materials can be a complex, costly conundrum.

Often, an expert operator must use manual trial-and-error—possibly making thousands of prints—to determine ideal parameters that consistently print a new material effectively. These parameters include printing speed and how much material the printer deposits.

MIT researchers have now used artificial intelligence to streamline this procedure. They developed a machine-learning system that uses computer vision to watch the manufacturing process and then correct errors in how it handles the material in real-time.

Researchers 3D print high-performance nanostructured alloy that’s both ultrastrong and ductile

Researchers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and the Georgia Institute of Technology have 3D printed a dual-phase, nanostructured high-entropy alloy that exceeds the strength and ductility of other state-of-the-art additively manufactured materials, which could lead to higher-performance components for applications in aerospace, medicine, energy and transportation.

The work, led by Wen Chen, assistant professor of mechanical and industrial engineering at UMass, and Ting Zhu, professor of mechanical engineering at Georgia Tech, is published by the journal Nature (“Strong yet ductile nanolamellar high-entropy alloys by additive manufacturing”).

Wen Chen, assistant professor of mechanical and industrial engineering at UMass Amherst, stands in front of images of 3D printed high-entropy alloy components (heatsink fan and octect lattice, left) and a cross-sectional electron backscatter diffraction inverse-pole figure map demonstrating a randomly oriented nanolamella microstructure (right). (Image: UMass Amherst)

How 3D Printing Can Help in Your Medical Device Manufacturing Project

The subtractive manufacturing process involves etching, drilling, or cutting from a solid board to build the final product. It is ideal for applications using a wide variety of materials and in the PCB fabrication of large-size products. In the additive manufacturing process, a product is developed by adding material one layer at a time and bonding the layers together until the final product is ready. The ability to control material density and the possibility of including intricate features makes this process versatile. It is used in a range of engineering and manufacturing applications, especially in custom manufacturing.

Benefits of 3D printing in medical device manufacturing.

3D printing is economical and offers quick PCB prototyping without the need for complex manufacturing steps. It optimizes the PCB design process by avoiding possible design faults in the initial PCB design stages. 3D printing is easy on flex PCBs and multilayer PCB printing is possible using the latest design software. With the growing manufacturing trends and improving software, 3D printing will be more than a prototyping tool and can be a viable alternative for production parts. 3D printing has been recently used for the end-part manufacturing of several medical devices like hearing aids, dental implants, and more. It is more beneficial for low-volume productions.

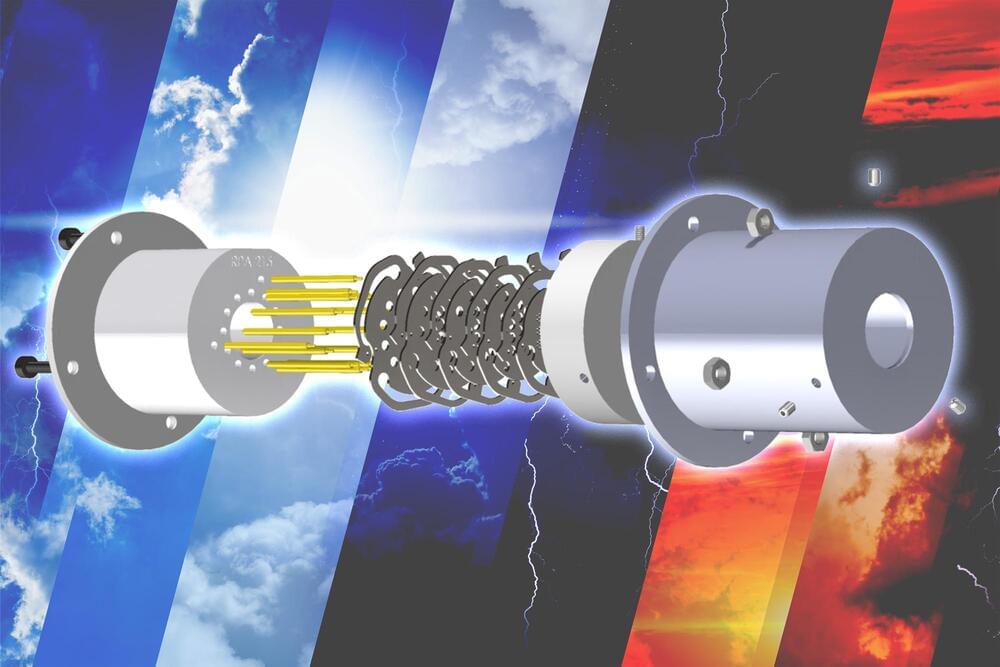

Researchers 3D print sensors for satellites

Caption :

MIT researchers have demonstrated a 3D-printed plasma sensor for orbiting spacecraft that works just as well as much more expensive, semiconductor sensors. These durable, precise sensors could be used effectively on inexpensive, lightweight satellites known as CubeSats, which are commonly utilized for environmental monitoring or weather prediction.

‘to grow a building’ uses 3D printing to create organic architecture made of seeds and soil

To grow a building at jerusalem design week 2022 For Jerusalem Design Week 2022, the 11th edition of Israel’s foremost annual design event, a group of designers took to Hansen House to present ‘To Grow a Building’, an outdoor performative lab that imagined the possibility of a world in which…

Jerusalem design week 2022 presents ‘to grow a building’, a performative lab that imagines a 3D printed organic architecture.

Scientists develop new ‘biohybrid composite’ for 3D printing lifelike artificial skin

Researchers at Cornell University have come up with a novel biomaterial that can be used to create artificial skin capable of mimicking the behavior of natural human tissues.

Thanks to its unique composition, made up of collagen mixed with a ‘zwitterionic’ hydrogel, the team’s biohybrid composite is said to be soft and biocompatible, but flexible enough to withstand continued distortion. While the scientists’ R&D project remains ongoing, they say their bio-ink could one day be used as a basis for 3D printing scaffolds from patients’ cells, which effectively heal wounds in-situ.

“Ultimately, we want to create something for regenerative medicine purposes, such as a piece of scaffold that can withstand some initial loads until the tissue fully regenerates,” said Nikolaos Bouklas, one of the study’s co-lead authors. “With this material, you could 3D print a porous scaffold with cells that could eventually create the actual tissue around the scaffold.”

Temperature-resistant power semiconductors from a 3D printer

Researchers at the Professorship of Electrical Energy Conversion Systems and Drives at Chemnitz University of Technology have succeeded for the first time in 3D printing housings for power electronic components that are used, for example, to control electrical machines. During the printing process, silicon carbide chips are positioned at a designated point on the housing.

As with the printed motor made of iron, copper and ceramics, which the professorship first presented at the Hannover Messe in 2018, ceramic and metallic pastes are also used in the 3D printing of housings. “These are sintered after the printing process, together—and this is what makes them special—with the imprinted chip,” says Prof. Dr. Ralf Werner, head of the Professorship of Electrical Energy Conversion Systems and Drives. Ceramic is used as an insulating material and copper is used for contacting the gate, drain and source areas of the field-effect transistors. “Contacting the gate area, which normally has an edge length of less than one millimeter, was particularly challenging,” adds Prof. Dr. Thomas Basler, head of the Professorship of Power Electronics, whose team supported the project with initial functional tests on prototypes.

Following the ceramic-insulated coils printed at Chemnitz University of Technology, which were presented at the Hannover Messe in 2017, and the printed motor, drive components that can withstand temperatures above 300 °C are now also available. “The desire for more temperature-resistant power electronics was obvious, because the housings for power electronic components are traditionally installed as close as possible to the engine and should therefore have an equally high temperature resistance,” says Prof. Werner.

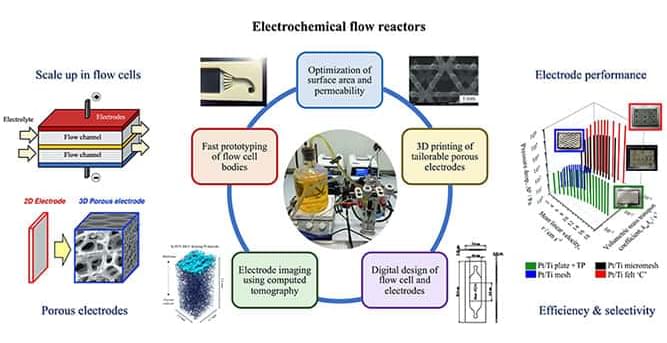

Using colloidal nanodiscs for 3D bioprinting tissues and tissue models

Extrusion-based 3D printing/bioprinting is a promising approach to generating patient-specific, tissue-engineered grafts. However, a major challenge in extrusion-based 3D printing and bioprinting is that most currently used materials lack the versatility to be used in a wide range of applications.

New nanotechnology has been developed by a team of researchers from Texas A&M University that leverages colloidal interactions of nanoparticles to print complex geometries that can mimic tissue and organ structure. The team, led by Dr. Akhilesh Gaharwar, associate professor and Presidential Impact Fellow in the Department of Biomedical Engineering, has introduced colloidal solutions of 2D nanosilicates as a platform technology to print complex structures.

2D nanosilicates are disc-shaped inorganic nanoparticles 20 to 50 nanometers in diameter and 1 to 2 nanometers in thickness. These nanosilicates form a “house-of-cards” structure above a certain concentration in water, known as a colloidal solution.