Circa 2021:3

Surgical management of breast cancer often results in the absence of the breast. However, existing breast reconstruction methods may not meet the need for a replacement tissue. Tissue engineering with the use of emerging materials offers the promise of generating appropriate replacements. Three-dimensional (3D) printing technology has seen a significantly increased interest and application in medically-related fields in the recent years. This has been especially true in complex medical situations particularly when abnormal or complicated anatomical surgical considerations or precise reconstructive procedures are contemplated. In addition, 3D bio-printing which combines cells with bio-material scaffolds offers an exciting technology with significant applications in the field of tissue engineering. The purpose of this manuscript was to review a number of studies in which 3D printing technology has been used in breast reconstructive surgical procedures, and future directions and applications of 3D bio-printing.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer diagnosed among US women and is second only to lung cancer as a cause of cancer death among women as of 2019. Because ~268,600 (almost six times than DCIS) new cases prove to be an invasive type of breast cancer (1), many women had to choose the removal of the breast, with immediate consideration for a replacement tissue. Although this was satisfactory in many patients, either saline or gel-filled breast implants (2) do carry real risks of complications such as infection, capsular contracture, implant dislocation, or deformities (3, 4). The option of autologous reconstruction can be more texturally natural aesthetically, but it requires a more complex procedure, significant time and expense, and possible muscle weakness or hernia formation at the tissue donor site (5). Tissue engineering intends to address these limitations by combining the 3D printing technology with synthetic or natural structural elements.

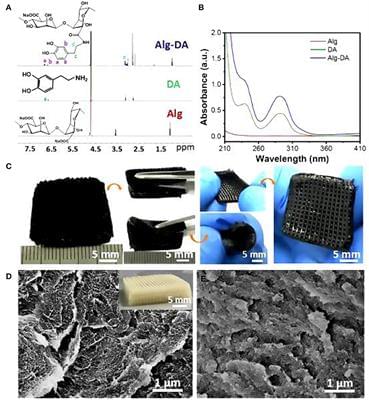

Three-dimensional (3D) printing, also known as computer-aided manufacturing (CAM), was based on digital model files using metal powder or plastic and other adhesive materials to construct objects with a computer guided precision, printing layer upon layer. Simplistically, it uses a computer aided design (CAD) program to convert the virtual model of an object into a printable object using an STL (Standard Tessellation Language or STereoLithography) file. The object then gradually and precisely takes shape as each thin layer is added according to the design file, and composed of the desired material for that object in the form of “ink” using the 3D printer. Not only in cases of intraoperative 3D printed models serving as templates, but this technology has extended to implanted scaffolds that have been used to correct defect-specific sites, clearly enhancing patient treatment (6, 7).