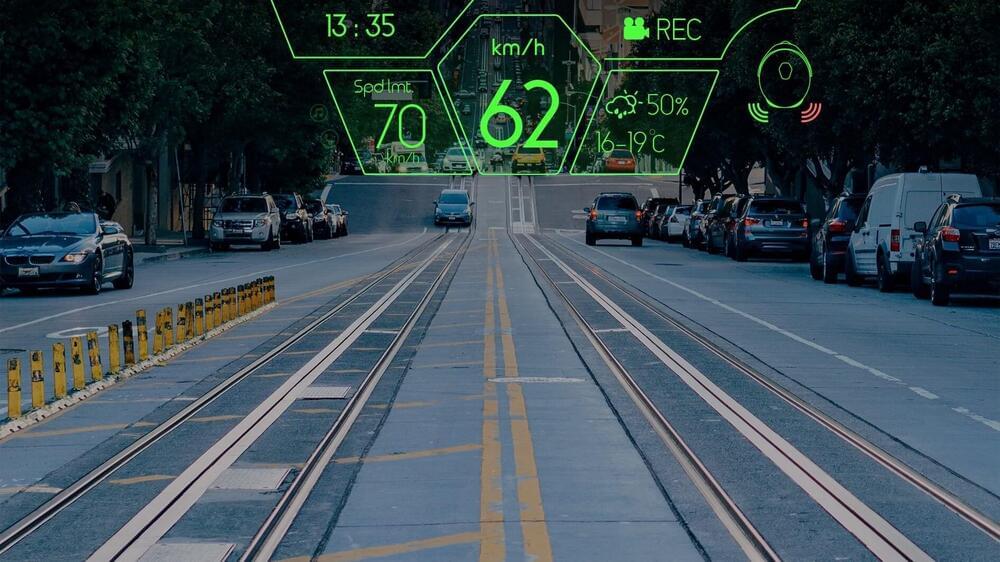

The world’s first flexible, transparent augmented reality (AR) display screen using 3D printing and low-cost materials has been created by researchers at the University of Melbourne, KDH Design Corporation and the Melbourne Centre for Nanofabrication (MCN). The development of the new display screen is set to advance how AR is used across a wide range of industries and applications.

AR technology overlays digital content onto the real world, enhancing the user’s real-time perception and interaction with their environment. Until now, creating flexible AR technology that can adjust to different angles of light sources has been a challenge, as current mainstream AR manufacturing uses glass substrates, which must undergo photomasking, lamination, cutting, or etching microstructure patterns. These time-consuming processes are expensive, have a poor yield rate and are difficult to seamlessly integrate with product appearance designs.

Led by University of Melbourne researchers Associate Professor Ranjith Unnithan, Professor Christina Lim and Professor Thas Nirmalathas, in collaboration with Taiwanese KDH Design Corporation, the team has successfully developed a transparent AR display screen using low-cost, optical-quality polymer and plastic—a first-of-its-kind achievement in the field of AR displays.