A group of 12 researchers at Rice University in Houston have used 3D printing to create near-bulletproof material made out of plastic. The novel materials can withstand being shot at by bullets traveling at 5.8 kilometers per second and are highly compressible without falling apart.

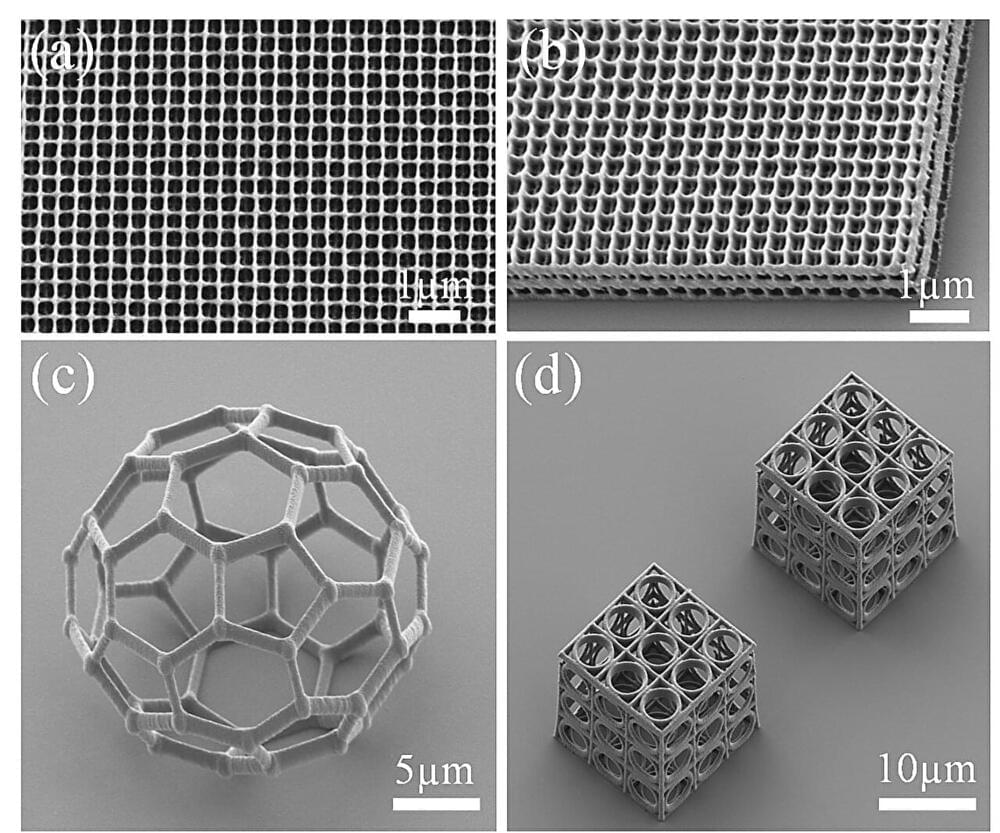

Tubulanes are theoretical microscopic structures comprised of crosslinked carbon nanotubes and the researchers sought to test if they would have the same properties when scaled up enough to be 3D printed. It turns out they did.

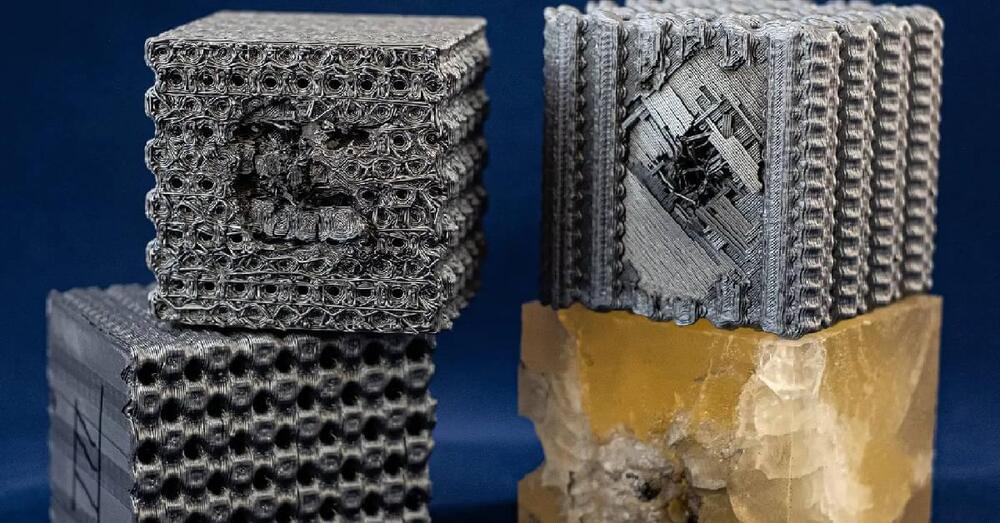

The researchers proved this by shooting a bullet traveling at 5.8 kilometers per second through two cubes. One cube was made from a solid polymer and the other from a polymer printed with a tubulane structure.

By subscribing, you agree to our Terms of Use and Policies You may unsubscribe at any time.

RELATED: THE BLACKEST BLACK: MIT ENGINEERS DEVELOP a MATERIAL SO DARK, THAT IT MAKES THINGS DISAPPEAR