Anil Seth explains why our conscious experience is a world we build from the inside out, rather than from the outside in

Get the latest international news and world events from around the world.

Meet the new biologists treating LLMs like aliens

How large is a large language model? Think about it this way.

In the center of San Francisco there’s a hill called Twin Peaks from which you can view nearly the entire city. Picture all of it—every block and intersection, every neighborhood and park, as far as you can see—covered in sheets of paper. Now picture that paper filled with numbers.

That’s one way to visualize a large language model, or at least a medium-size one: Printed out in 14-point type, a 200-billion-parameter model, such as GPT4o (released by OpenAI in 2024), could fill 46 square miles of paper—roughly enough to cover San Francisco. The largest models would cover the city of Los Angeles.

We now coexist with machines so vast and so complicated that nobody quite understands what they are, how they work, or what they can really do—not even the people who help build them. “You can never really fully grasp it in a human brain,” says Dan Mossing, a research scientist at OpenAI.

That’s a problem. Even though nobody fully understands how it works—and thus exactly what its limitations might be—hundreds of millions of people now use this technology every day. If nobody knows how or why models spit out what they do, it’s hard to get a grip on their hallucinations or set up effective guardrails to keep them in check. It’s hard to know when (and when not) to trust them.

Whether you think the risks are existential—as many of the researchers driven to understand this technology do—or more mundane, such as the immediate danger that these models might push misinformation or seduce vulnerable people into harmful relationships, understanding how large language models work is more essential than ever.

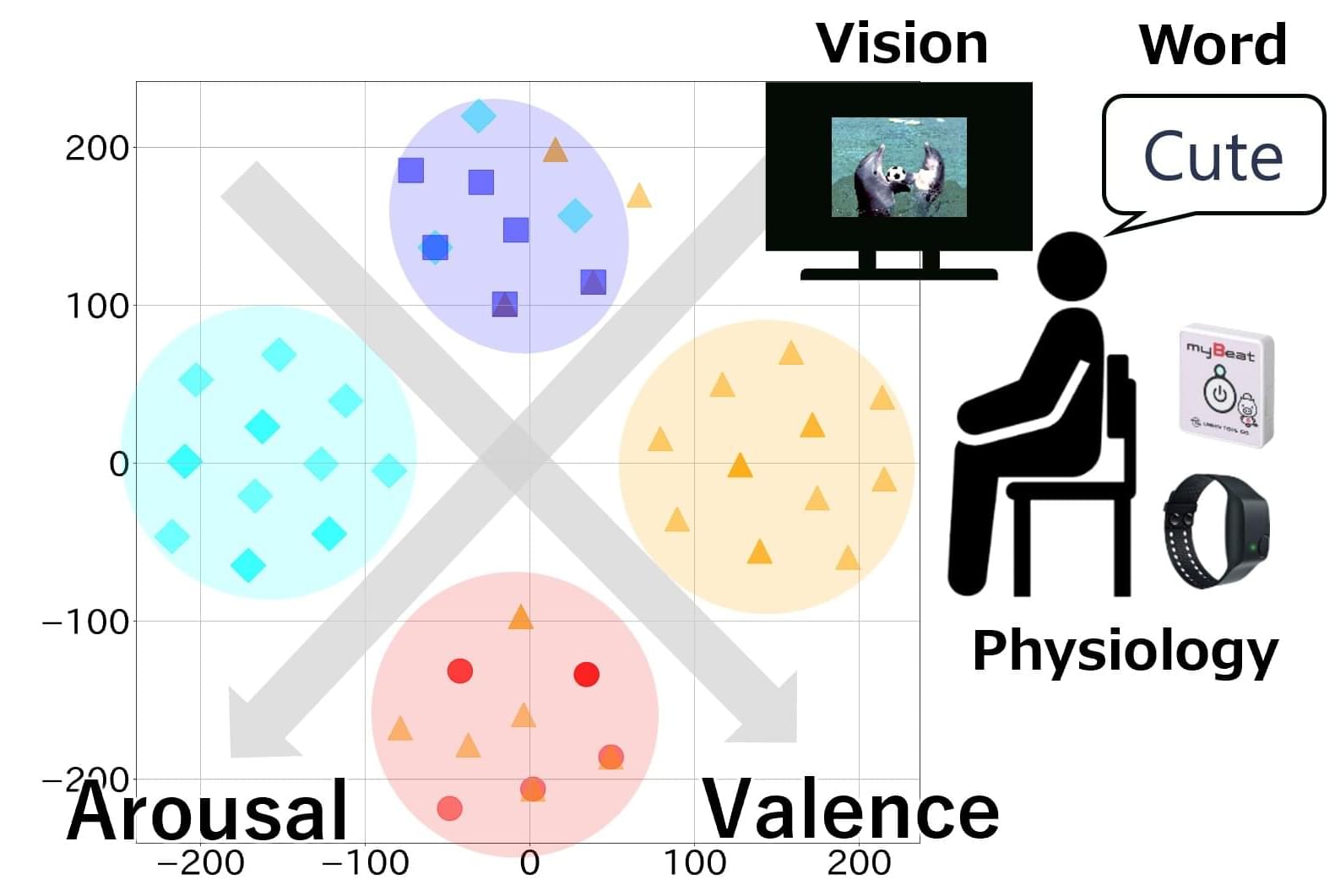

Using AI to understand how emotions are formed

Emotions are a fundamental part of human psychology—a complex process that has long distinguished us from machines. Even advanced artificial intelligence (AI) lacks the capacity to feel. However, researchers are now exploring whether the formation of emotions can be computationally modeled, providing machines with a deeper, more human-like understanding of emotional states.

In this vein, Assistant Professor Chie Hieida from the Nara Institute of Science and Technology (NAIST), Japan, in collaboration with Assistant Professor Kazuki Miyazawa and then-master’s student Kazuki Tsurumaki from Osaka University, Japan, explore computational approaches to model the formation of emotions.

The team built a computational model that aims to explain how humans may form the concept of emotion. The study was published in the journal IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing.

NASA supercomputer just predicted Earth’s hard limit for life

Scientists have used a NASA-grade supercomputer to push our planet to its limits, virtually fast‑forwarding the clock until complex organisms can no longer survive. The result is a hard upper bound on how long Earth can sustain breathable air and liquid oceans, and it is far less about sudden catastrophe than a slow suffocation driven by the Sun itself. The work turns a hazy, far‑future question into a specific timeline for the end of life as we know it.

Instead of fireballs or rogue asteroids, the simulations point to a world that quietly runs out of oxygen, with only hardy microbes clinging on before even they disappear. It is a stark reminder that Earth’s habitability is not permanent, yet it also stretches over such vast spans of time that our immediate crises still depend on choices made this century, not on the Sun’s distant evolution.

The new modeling effort starts from a simple premise: if I know how the Sun brightens over time and how Earth’s atmosphere responds, I can calculate when conditions for complex life finally fail. Researchers fed a high‑performance system with detailed physics of the atmosphere, oceans and carbon cycle, then let it run through hundreds of thousands of scenarios until the planet’s chemistry tipped past a critical point. One study describes a supercomputer simulation that projects life on Earth ending in roughly 1 billion years, once rising solar heat strips away most atmospheric oxygen.

Smart Golden Cities of the Future: 1 Hour Exploring Nature & Sci-Fi Innovation in 2050

Step into the future with “Smart Golden Cities of the Future”, a 1-hour journey exploring how technology and nature will merge to create sustainable, intelligent cities by 2050. In this immersive video, we’ll dive deep into a world where urban spaces are powered by Sci-Fi innovation, green infrastructure, and advanced technologies. From eco-friendly architecture to autonomous transportation systems, discover how the cities of tomorrow will function in harmony with the environment. Imagine a future with clean energy, smart public services, and a thriving connection to nature—where sustainability and futuristic technology drive every aspect of life. Join us for an hour-long exploration of the Smart Cities of 2050, as we uncover the incredible possibilities and challenges of creating urban spaces that work for both people and the planet. ✨ This video was created with passion and love for sharing creative production using AI tools such as: • 🧠 Research: ChatGPT • 🖼️ Image Creation: Leonardo, Midjourney, ImageFX • 🎬 Video Production: Veo 3.1, Runway ML • 🎵 Music Generation: Suno AI • ✂️ Video Editing: CapCut Pro 💡 Note: All of the above AI tools are subscription-based. This project combines imagination and creativity from my perspective as a mechanical engineer who loves exploring the future. 🙏🏻 Please Support: • ✅ Subscribe • 👍 Like • 💬 Comment Thank you so much for watching!I hope you enjoy this journey and gain inspiration from this creative experience ❤️ #SmartCities #Sustainability #FutureOfLiving #SciFiInnovation #EcoFriendlyCities #midjourney #veo3 #sunoai

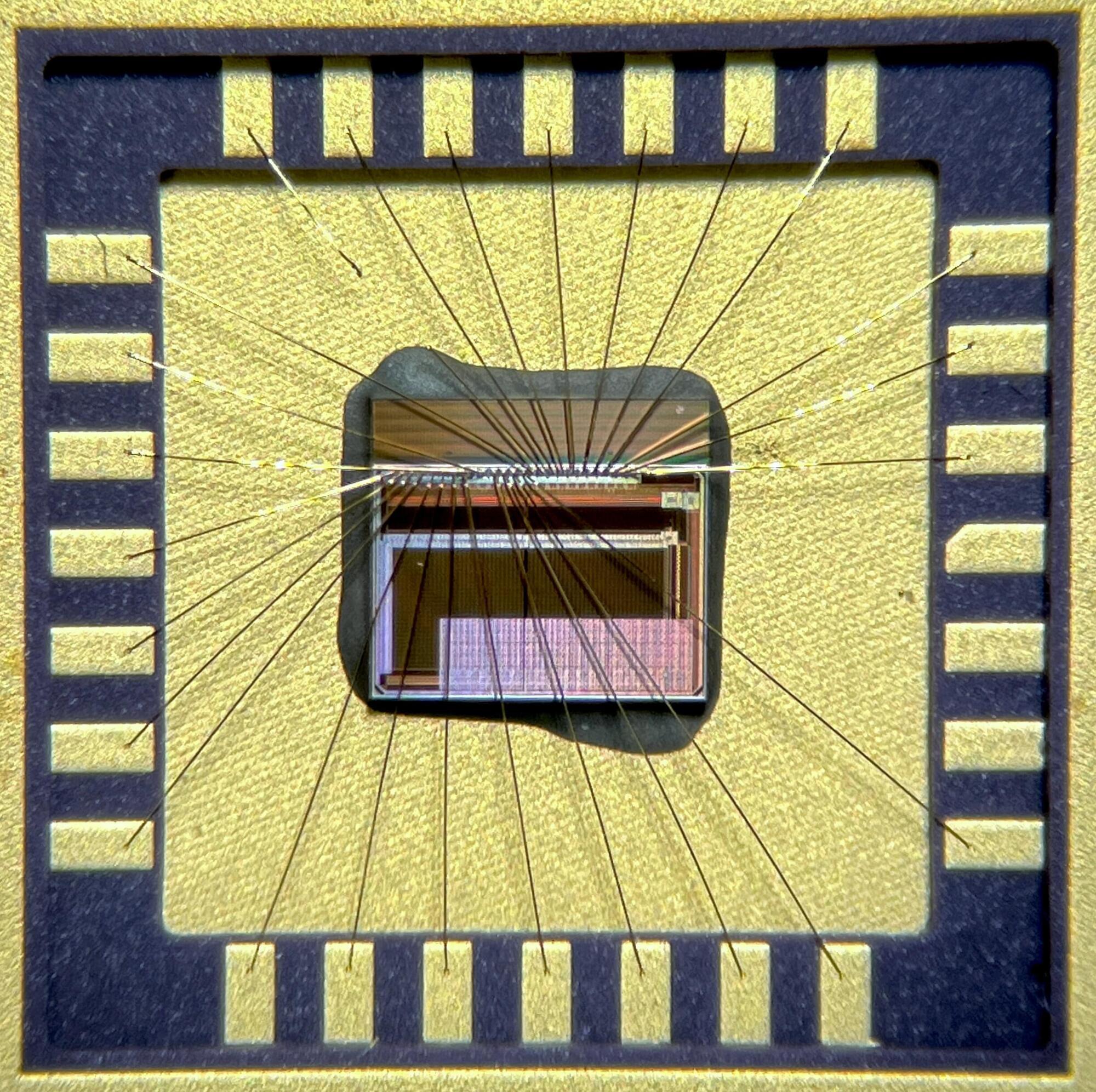

New smart chip reduces consumption and computing time, advancing high-performance computing

A new chip aims to dramatically reduce energy consumption while accelerating the processing of large amounts of data.

A paper on this work appears in the journal Nature Electronics.

The chip was developed by a group of researchers from the Department of Electronics, Information and Bioengineering–DEIB at the Politecnico di Milano, led by Professor Daniele Ielmini, with researcher Piergiulio Mannocci as the first author.

Scientists identify promising new target for Alzheimer’s-linked brain inflammation

A multidisciplinary team has developed a selective compound that inhibits an enzyme tied to inflammation in people at genetic risk for Alzheimer’s, while preserving normal brain function and crossing the blood-brain barrier.

The findings are published in the journal npj Drug Discovery.

The driver is an enzyme called calcium-dependent phospholipase A2 (cPLA2). The team discovered its role in brain inflammation by studying people who carry the APOE4 gene —the strongest genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. While many people who have the APOE4 gene don’t develop the disease, those with elevated levels of cPLA2 generally do.

Video: Why ‘basic science’ is the foundation of innovation

At first glance, some scientific research can seem, well, impractical. When physicists began exploring the strange, subatomic world of quantum mechanics a century ago, they weren’t trying to build better medical tools or high-speed internet. They were simply curious about how the universe worked at its most fundamental level.

Yet without that “curiosity-driven” research—often called basic science—the modern world would look unrecognizable.

“Basic science drives the really big discoveries,” says Steve Kahn, UC Berkeley’s dean of mathematical and physical sciences. “Those paradigm changes are what really drive innovation.”