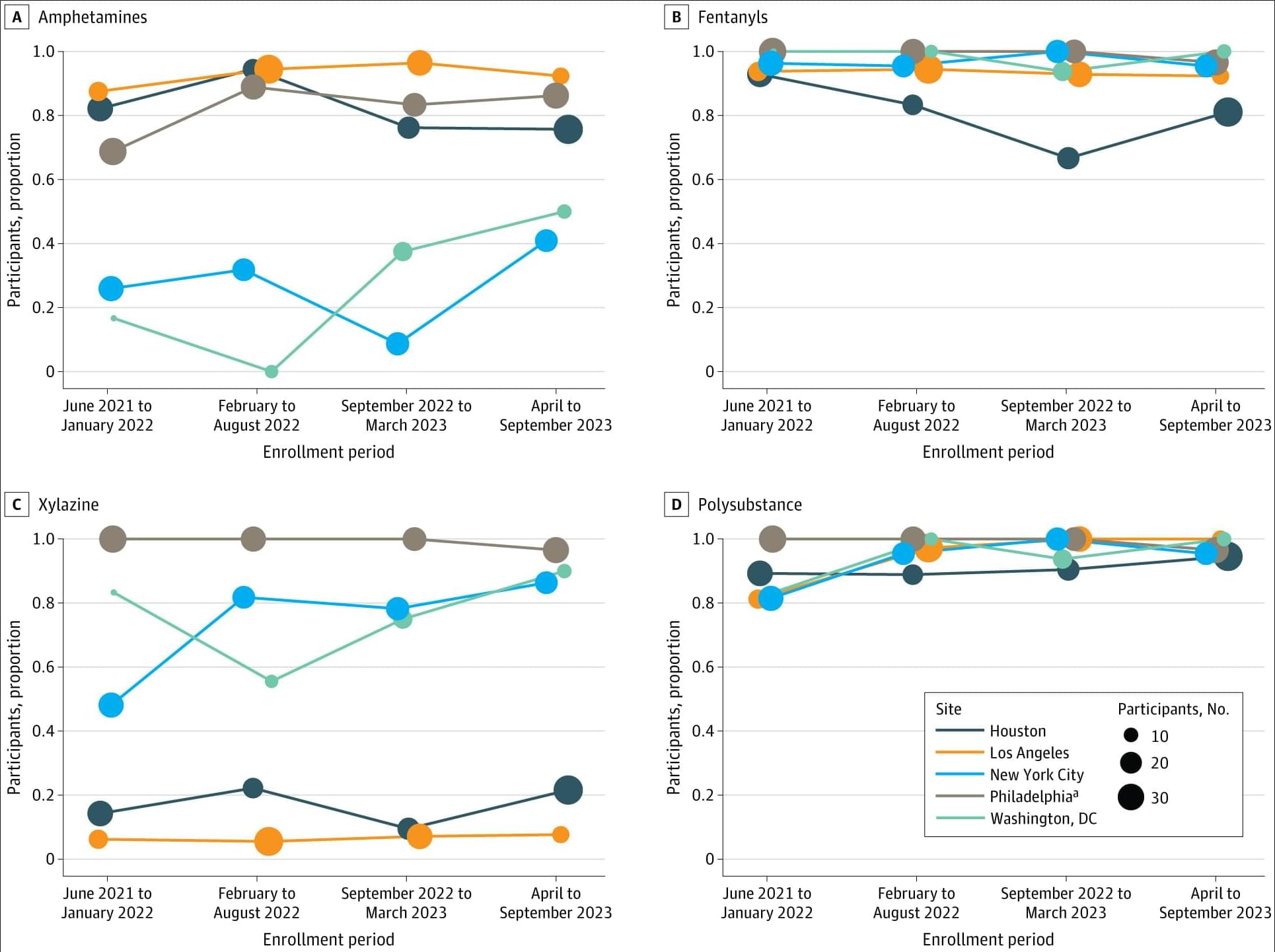

Among people injecting drugs and not engaged in medical care, nearly all tested positive for fentanyl and multiple other substances, with polysubstance and xylazine detection rates highest among unhoused and recently incarcerated participants.

This cross-sectional study used data from HPTN 094. Participants who met eligibility criteria were invited to participate in a baseline interview and were enrolled between June 2021 and September 2023. All participants completed written informed consent prior to participating in study procedures, and a single institutional review board (Advarra) provided ethical approval for HPTN 094; this cross-sectional analysis was exempt from additional IRB approval. The current study was conducted and reported in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.23

Participants were required to meet the following criteria: be at least 18 years of age, have a urine test positive for recent opioid use and evidence of recent injection drug use (visible venipuncture marks), meet diagnostic criteria for opioid use disorder, be able to give informed consent, be willing to start MOUD treatment, complete an assessment of understanding, have confirmed HIV seropositivity or self-reported sharing of injection equipment and/or condomless sex in the past 3 months with partners living with HIV or with unknown HIV status, and provide locator information. Participants were excluded if they self-reported being prescribed MOUD in the 30 days prior to screening, had a urine test positive for methadone (with the exception of verified hospitalization), or were enrolled in another study.