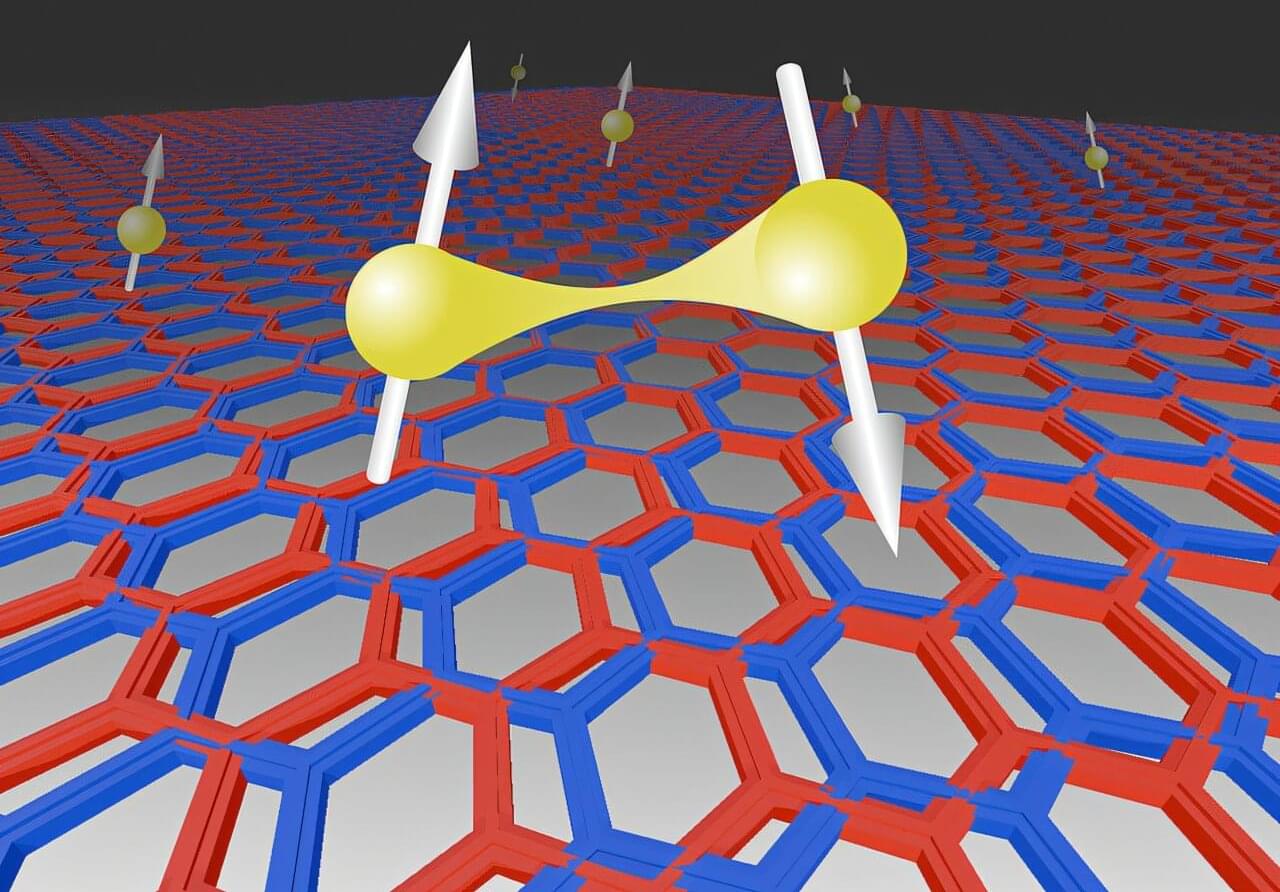

Proteins are the molecular machines of cells. They are produced in protein factories called ribosomes based on their blueprint—the genetic information. Here, the basic building blocks of proteins, amino acids, are assembled into long protein chains. Like the building blocks of a machine, individual proteins must have a specific three-dimensional structure to properly fulfill their functions.

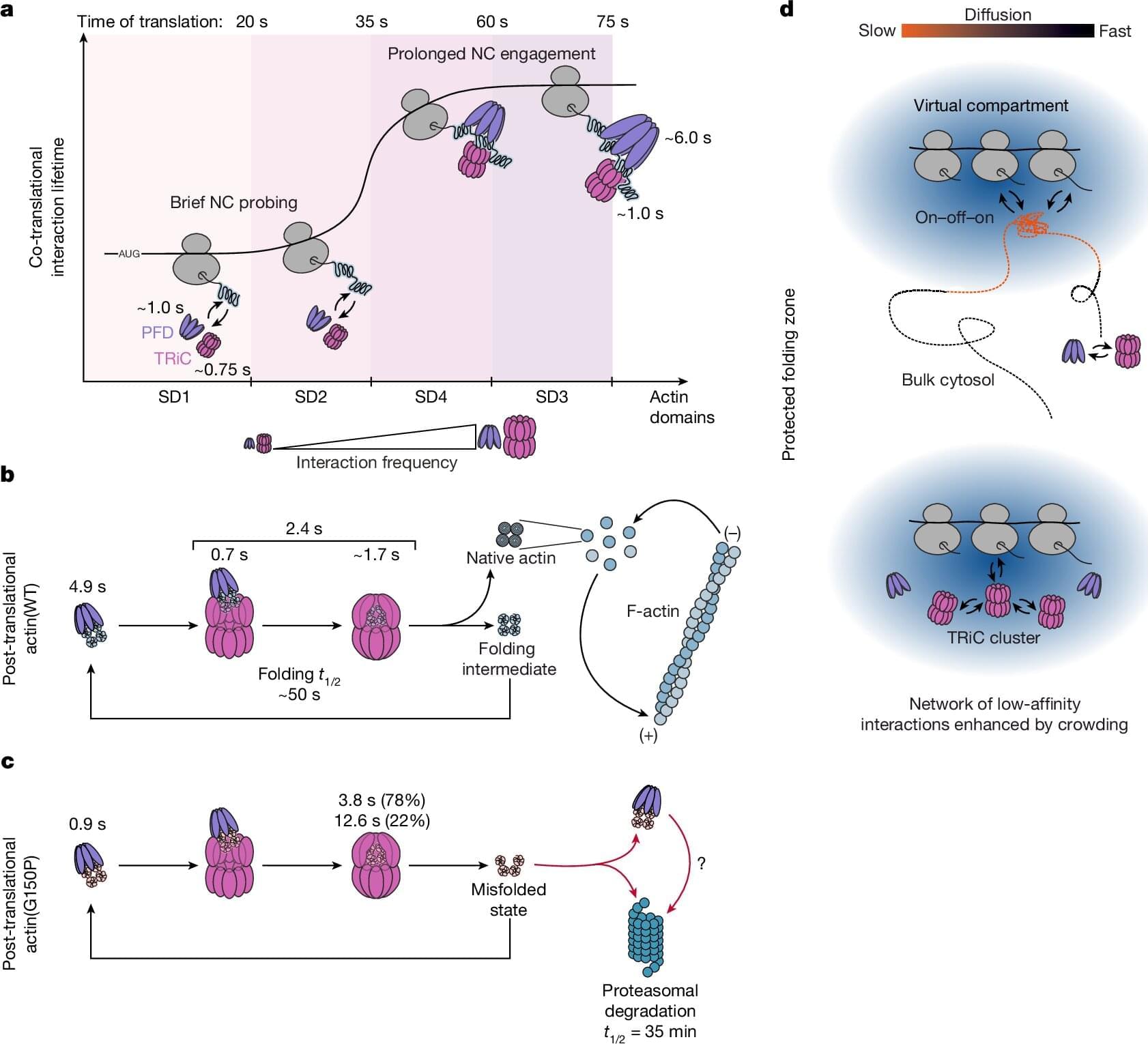

To achieve this, the newly produced protein chains in human cells are folded into their stable and functional form with the help of various protein folding helper proteins, known as chaperones, such as TRiC/PFD, or HSP70/40. The protein folding helpers isolate the amino acid chains, which have different chemical properties depending on the amino acid, from the cellular environment. This prevents the newly produced protein chains from clumping together and causing disease.

F.-Ulrich Hartl, a director at the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry, has spent decades studying the mechanisms of protein folding. Niko Dalheimer, a scientist in Hartl’s department and one of the two lead authors of a new study published in Nature, explains: Much of what we know about protein folding has been learned from studies conducted in test tubes. However, it is virtually impossible to faithfully replicate the cellular environment in vitro.