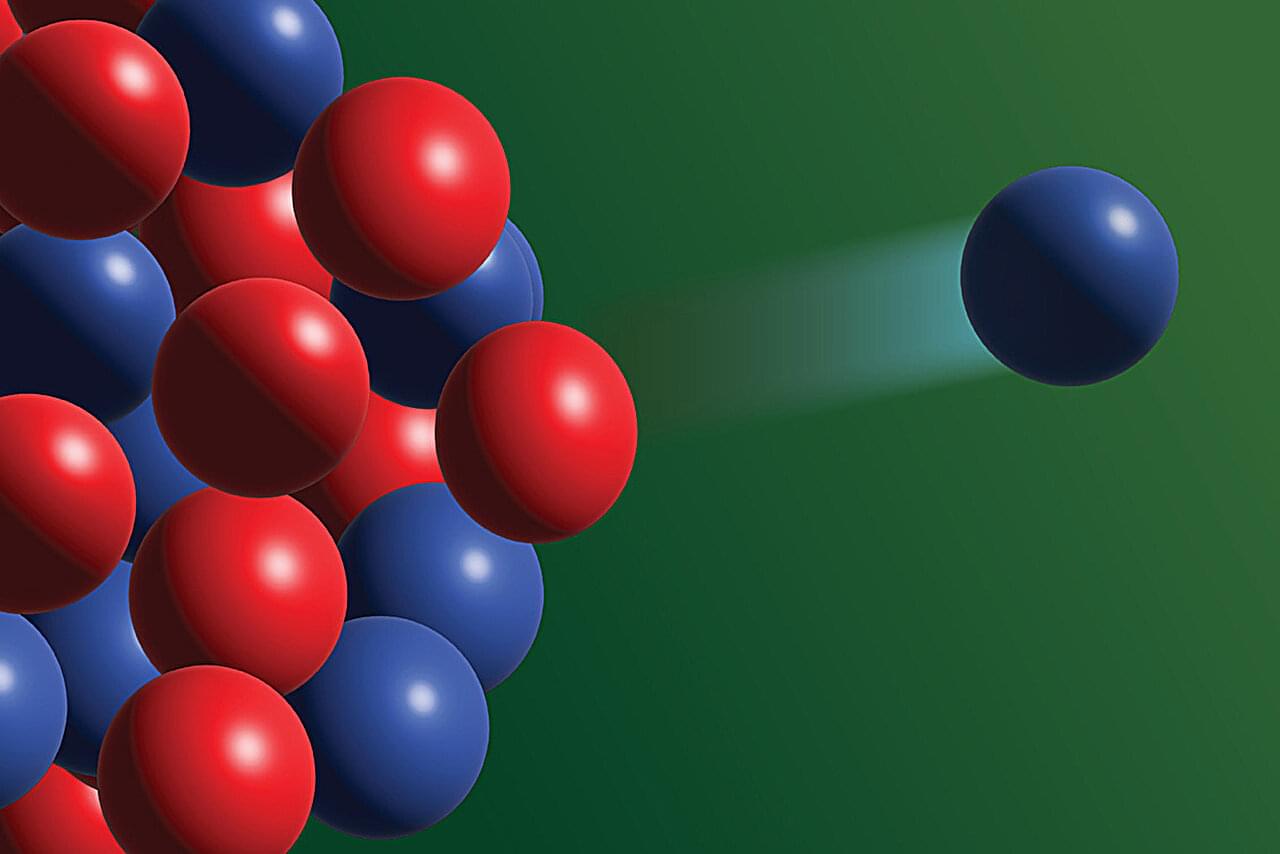

A research team at the Facility for Rare Isotope Beams (FRIB) is the first ever to observe a beta-delayed neutron emission from fluorine-25, a rare, unstable nuclide. Using the FRIB Decay Station Initiator (FDSi), the team found contradictions in prior experimental findings. The results led to a new line of inquiry into how particles in exotic, unstable isotopes remain bound under extreme conditions. Led by Robert Grzywacz, professor of physics at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville (UTK), the team included Jack Peltier, undergraduate student at UTK, Zhengyu Xu, postdoctoral researcher at UTK, Sean Liddick, professor of chemistry at FRIB and interim chairperson of MSU’s Department of Chemistry, and Rebeka Lubna, scientist at FRIB.

The team published its results in Physics Letters B.

“The different results on decay lifetime we obtained for fluorine-25 were similar to previously measured decay of oxygen-24. And while we are not entirely certain why we found this difference between previously published results, we have conducted numerous checks on our results and are confident in our findings,” Grzywacz said.