Archaeologists have used laser technology to map a 100-km (62-mile) Maya stone road that could have been built 1,300 years ago to help with the invasion of an isolated city in modern-day Mexico. The ancient highway is thought to have been constructed at the command of the warrior queen Lady K’awiil Ajaw, and would have been coated in white plaster.

The 26 ft (8 m)-wide road, also known as Sacbe 1 or White Road 1, stretches from the ancient city of Cobá – one of the greatest cities of the Maya world – to the distant, smaller settlement of Yaxuná, located in the Yucatan Peninsula.

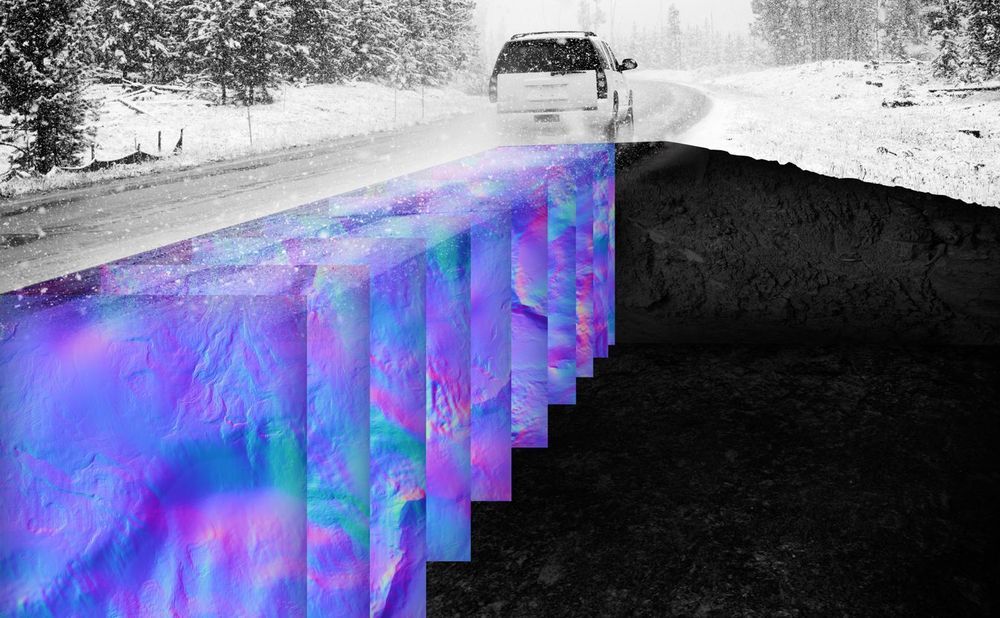

Newly-published research has shed new light on the nature of Lady K’awiil Ajaw’s great road by making use of light detection and ranging, otherwise known as LiDAR technology. To take their measurements, the authors made use of an airborne LiDAR instrument, which beamed lasers at the surface as it passed over the ancient road.