Governments set aside privacy concerns as they use surveillance software to fight Covid-19.

As we enter our third decade in the 21st century, it seems appropriate to reflect on the ways technology developed and note the breakthroughs that were achieved in the last 10 years.

The 2010s saw IBM’s Watson win a game of Jeopardy, ushering in mainstream awareness of machine learning, along with DeepMind’s AlphaGO becoming the world’s Go champion. It was the decade that industrial tools like drones, 3D printers, genetic sequencing, and virtual reality (VR) all became consumer products. And it was a decade in which some alarming trends related to surveillance, targeted misinformation, and deepfakes came online.

For better or worse, the past decade was a breathtaking era in human history in which the idea of exponential growth in information technologies powered by computation became a mainstream concept.

Historian Yuval Harari, author of Sapiens and Homo Deus, answers questions from the South China Morning Post on how the coronavirus pandemic poses unprecedented challenges in biometric surveillance, governance and global cooperation.

Yuval Harari says that unlike our ancestors battling plagues, we have science, wisdom and community on our side.

The potential threat of biological warfare with a specific agent is proportional to the susceptibility of the population to that agent. Preventing disease after exposure to a biological agent is partially a function of the immunity of the exposed individual. The only available countermeasure that can provide immediate immunity against a biological agent is passive antibody. Unlike vaccines, which require time to induce protective immunity and depend on the host’s ability to mount an immune response, passive antibody can theoretically confer protection regardless of the immune status of the host. Passive antibody therapy has substantial advantages over antimicrobial agents and other measures for postexposure prophylaxis, including low toxicity and high specific activity. Specific antibodies are active against the major agents of bioterrorism, including anthrax, smallpox, botulinum toxin, tularemia, and plague. This article proposes a biological defense initiative based on developing, producing, and stockpiling specific antibody reagents that can be used to protect the population against biological warfare threats.

Defense strategies against biological weapons include such measures as enhanced epidemiologic surveillance, vaccination, and use of antimicrobial agents, with the important caveat that the final line of defense is the immune system of the exposed individual. The potential threat of biological warfare and bioterrorism is inversely proportional to the number of immune persons in the targeted population. Thus, biological agents are potential weapons only against populations with a substantial proportion of susceptible persons. For example, smallpox virus would not be considered a useful biological weapon against a population universally immunized with vaccinia.

Vaccination can reduce the susceptibility of a population against specific threats provided that a safe vaccine exists that can induce a protective response. Unfortunately, inducing a protective response by vaccination may take longer than the time between exposure and onset of disease. Moreover, many vaccines require multiple doses to achieve a protective immune response, which would limit their usefulness in an emergency vaccination program to provide rapid prophylaxis after an attack. In fact, not all vaccine recipients mount a protective response, even after receiving the recommended immunization schedule. Persons with impaired immunity are often unable to generate effective response to vaccination, and certain vaccines may be contraindicated for them.

The initial cases of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)–infected pneumonia (NCIP) occurred in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, in December 2019 and January 2020. We analyzed data on the first 425 confirmed cases in Wuhan to determine the epidemiologic characteristics of NCIP.

Since December 2019, an increasing number of cases of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)–infected pneumonia (NCIP) have been identified in Wuhan, a large city of 11 million people in central China.1–3 On December 29, 2019, the first 4 cases reported, all linked to the Huanan (Southern China) Seafood Wholesale Market, were identified by local hospitals using a surveillance mechanism for “pneumonia of unknown etiology” that was established in the wake of the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak with the aim of allowing timely identification of novel pathogens such as 2019-nCoV.4 In recent days, infections have been identified in other Chinese cities and in more than a dozen countries around the world.5 Here, we provide an analysis of data on the first 425 laboratory-confirmed cases in Wuhan to describe the epidemiologic characteristics and transmission dynamics of NCIP.

Love this convergence of metaverse and fighting censorship with style. Wonder when Microsoft will start getting pressure about this or other kinds of content.

Most of us live in countries where freedom of speech is considered a fundamental human right and it would be hard to imagine living in a different state than that. However, not all of us are blessed with this sometimes overlooked right as there are a number of countries in this world where governments actively censor their citizens, especially those whose profession is to report facts. Journalists.

In a number of places around the world, journalists are banned, jailed, exiled, and even killed for their words. In order to make their message heard and reach the places where they’re banned, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) opened a special type of library that could reach millions. They built it in Minecraft.

The creators reason their choice by explaining the library’s accessibility: ” Reporters Without Borders (RSF) used this backdoor to build ” The Uncensored Library”: a library that is now accessible on an open server for Minecraft players around the globe. The library is filled with books containing articles that were censored in their country of origin. These articles are now available again within Minecraft—hidden from government surveillance technology inside a computer game. The books can be read by everyone on the server, but their content cannot be changed. The library is growing, with more and more books being added to overcome censorship.”

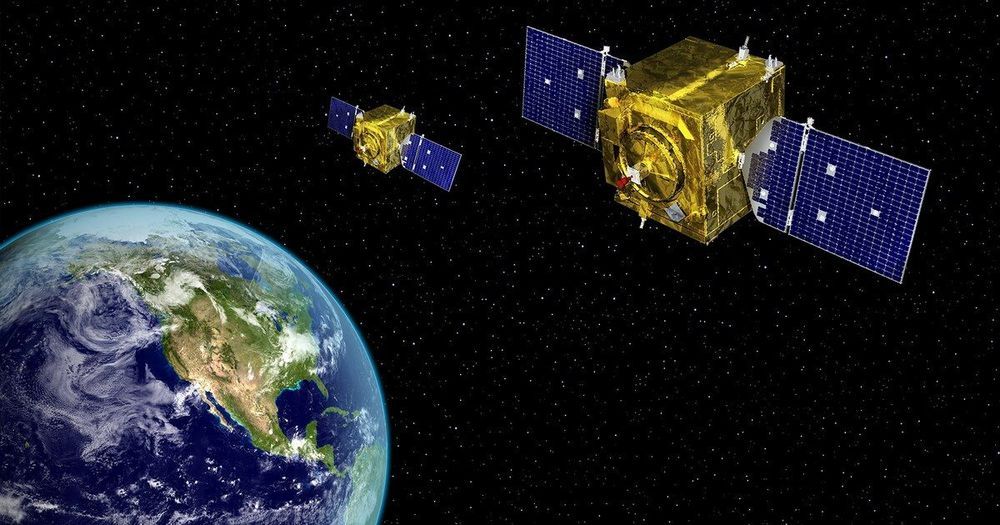

According to SOPS, this was one of the most significant upgrades to the system since it became operational in 2015. The ground system upgrade will also be important as the Space Force expands the constellation later this year, said 1st SOPS engineer Capt. Zachary Funke.

The first two satellites in the constellation launched in 2014, with two more satellites joining them on orbit in 2016. The Space Force is slated to launch the fifth and sixth GSSAP satellites in the fourth quarter of 2020 aboard an Atlas V rocket.

Operating near the geosynchronous belt, the four GSSAP satellites can provide data on other man-made objects in space without being interrupted by the weather or atmospheric conditions that impact ground-based space situational awareness systems. GSSAP satellites can also perform rendezvous and proximity operations, approaching other space vehicles to provide attribution or enhanced surveillance on objects of interest to United States Space Command.

Electromagnetic radiation, radar, and surveillance technology are used to transfer sounds and thoughts into people’s brain. UN started their investigation after receiving thousands of testimonies from so-called “targeted individuals” (TIs).”

Magnus Olsson, Geneva 8 March 2020

UN Human Rights Council (HRC) Special Rapporteur on torture revealed during the 43rd HRC that Cyber technology is not only used for internet and 5G. It is also used to target individuals remotely – through intimidation, harassment and public shaming.

On the 28th of February in Geneva, Professor Nils Melzer, UN Special Rapporteur on Torture and other Cruel Inhuman Degrading Treatment and Punishment, has officially confirmed that cyber torture exists and investigation is now underway on how to tackle it legally.

AI/Humans, our brave now world, happening now.

Are we facing a golden digital age or will robots soon run the world? We need to establish ethical standards in dealing with artificial intelligence — and to answer the question: What still makes us as human beings unique?

Mankind is still decades away from self-learning machines that are as intelligent as humans. But already today, chatbots, robots, digital assistants and other artificially intelligent entities exist that can emulate certain human abilities. Scientists and AI experts agree that we are in a race against time: we need to establish ethical guidelines before technology catches up with us. While AI Professor Jürgen Schmidhuber predicts artificial intelligence will be able to control robotic factories in space, the Swedish-American physicist Max Tegmark warns against a totalitarian AI surveillance state, and the philosopher Thomas Metzinger predicts a deadly AI arms race. But Metzinger also believes that Europe in particular can play a pioneering role on the threshold of this new era: creating a binding international code of ethics.

——————————————————————-

DW Documentary gives you knowledge beyond the headlines. Watch high-class documentaries from German broadcasters and international production companies. Meet intriguing people, travel to distant lands, get a look behind the complexities of daily life and build a deeper understanding of current affairs and global events. Subscribe and explore the world around you with DW Documentary.